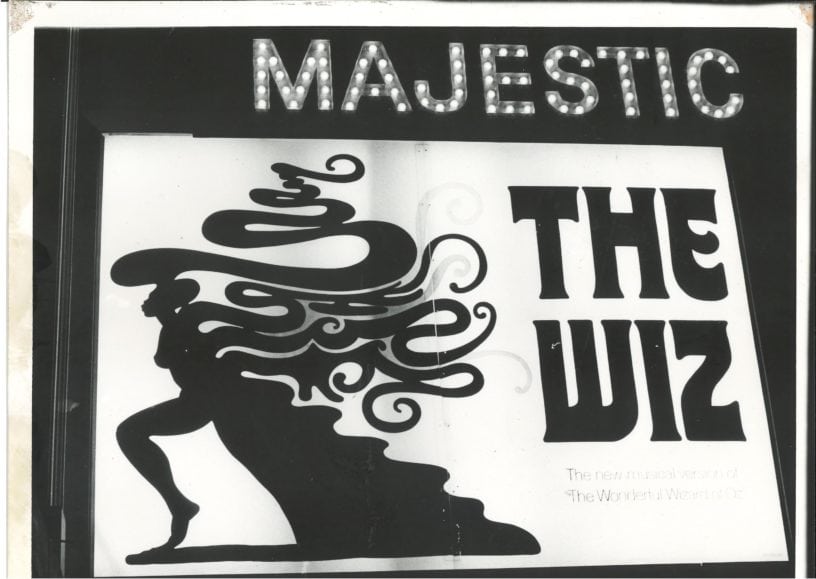

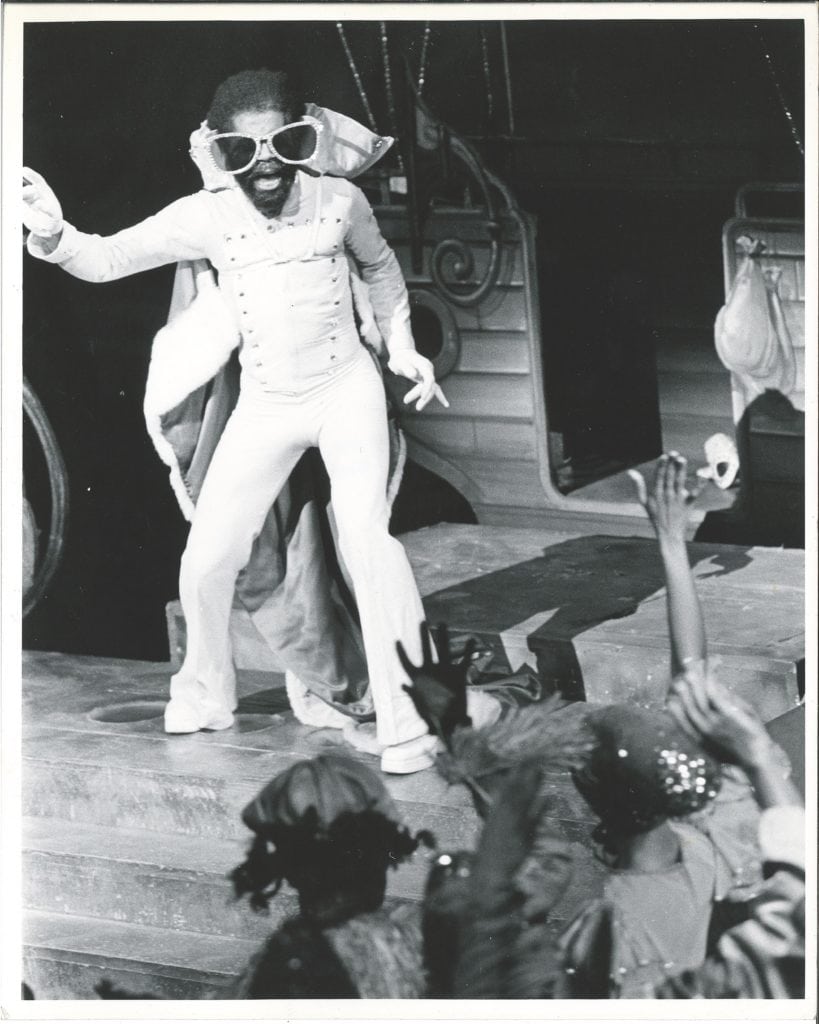

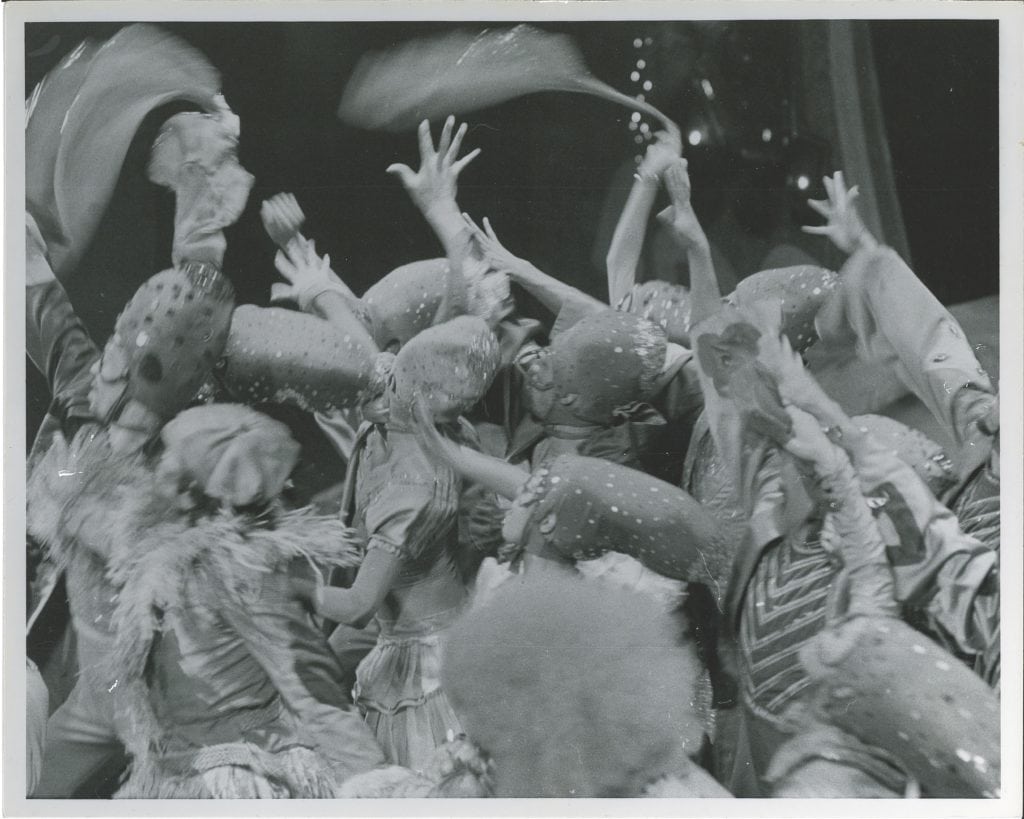

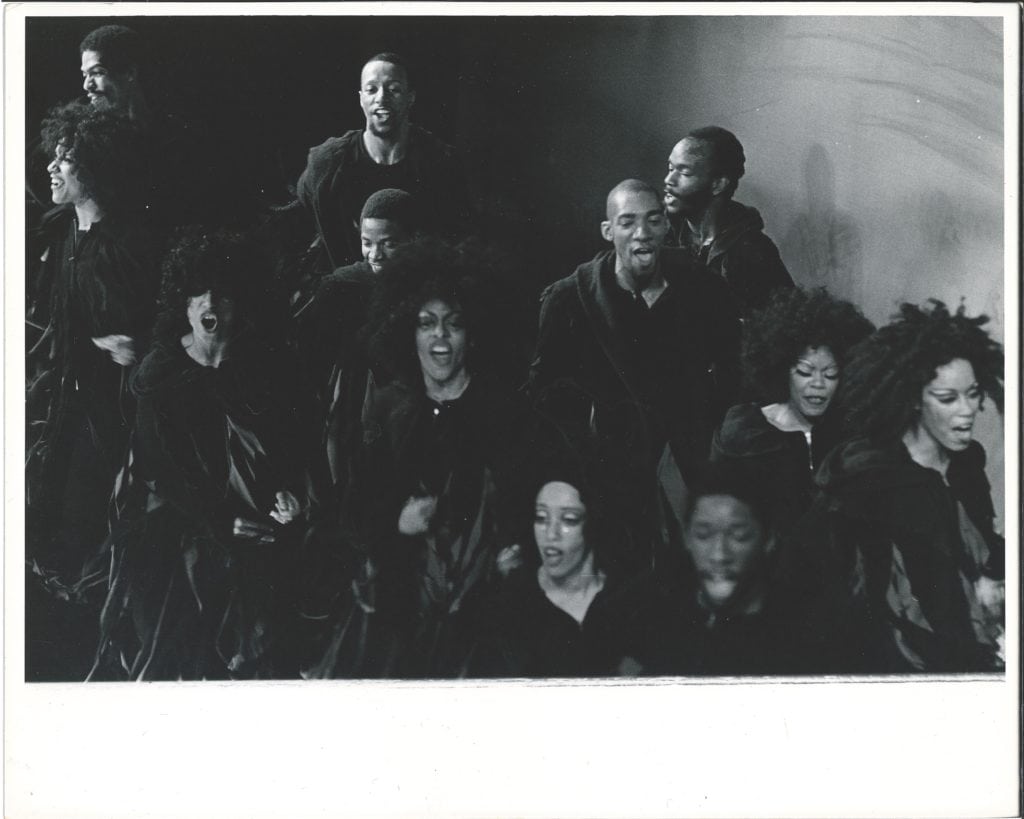

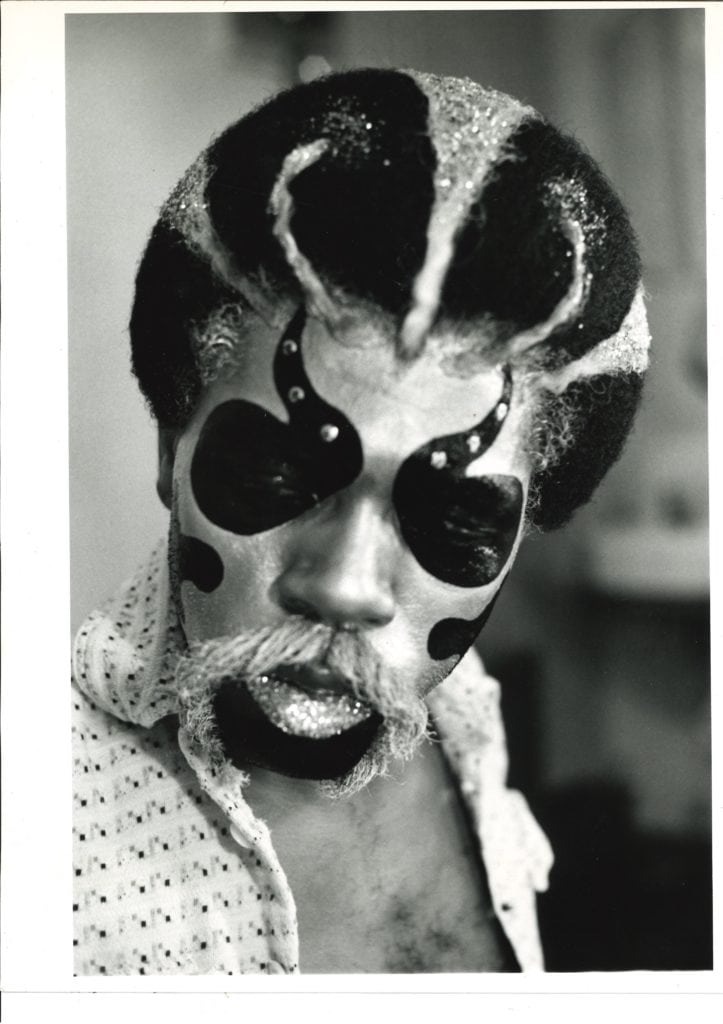

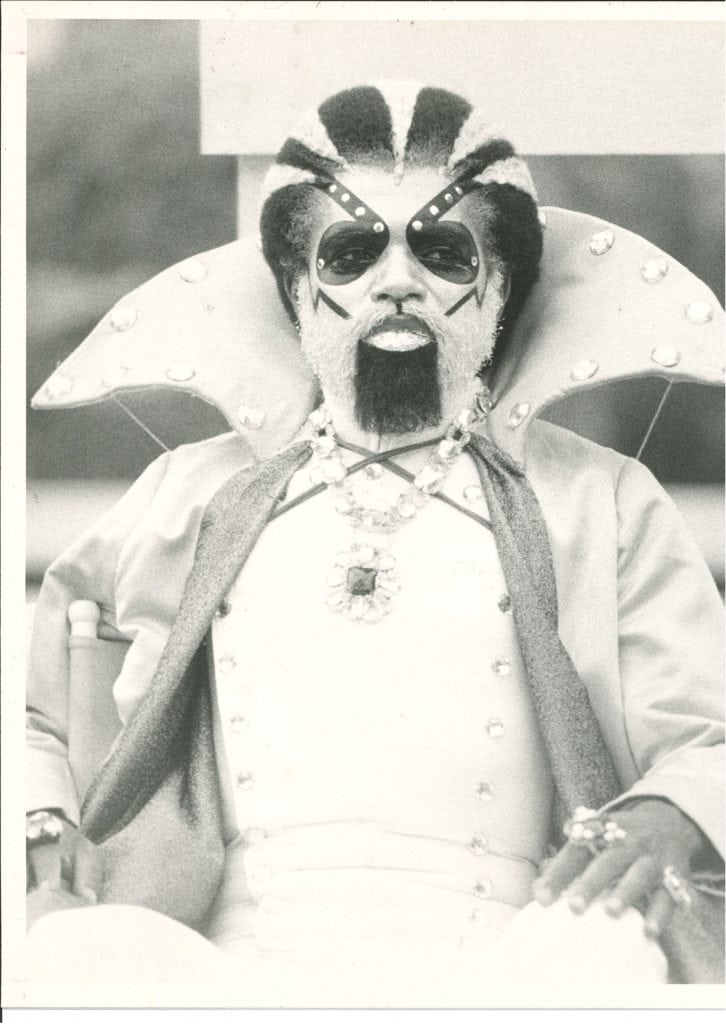

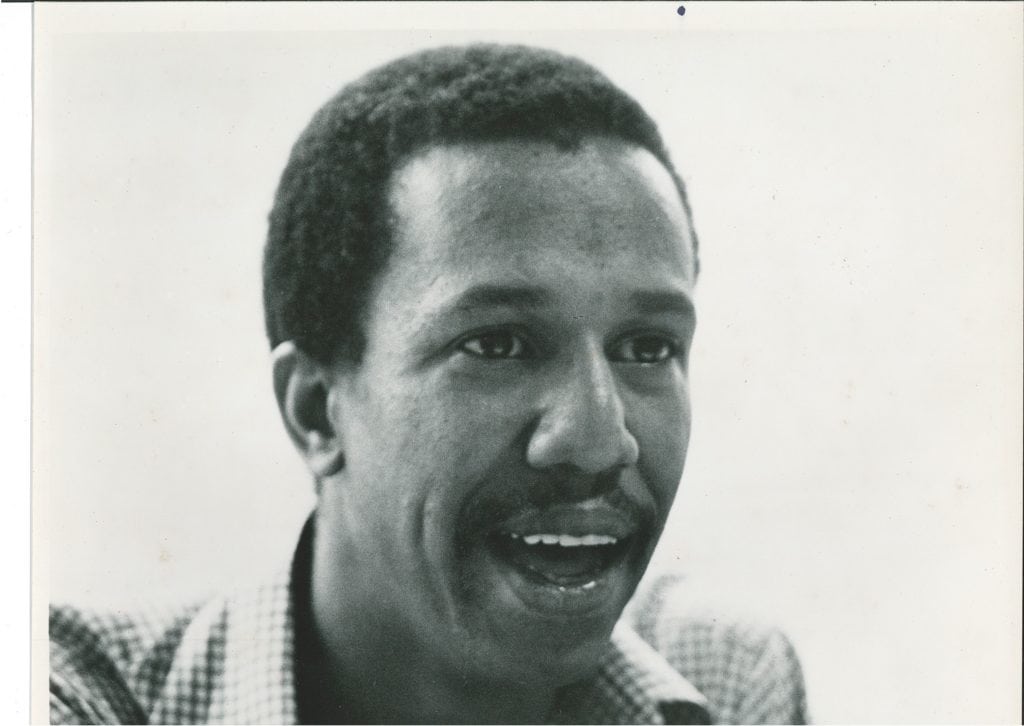

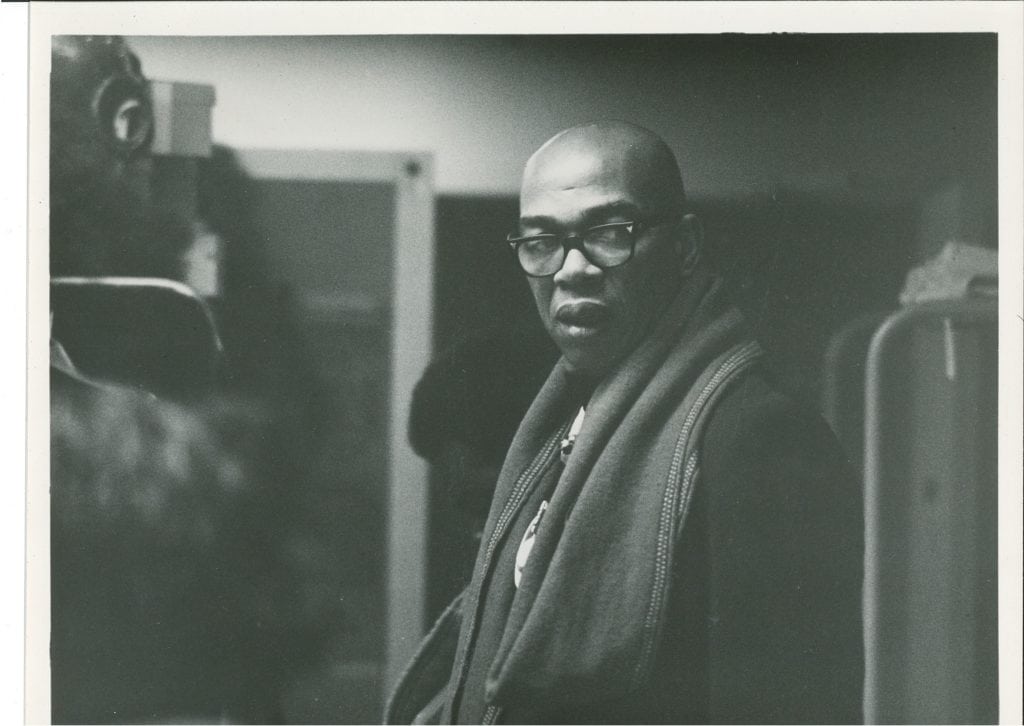

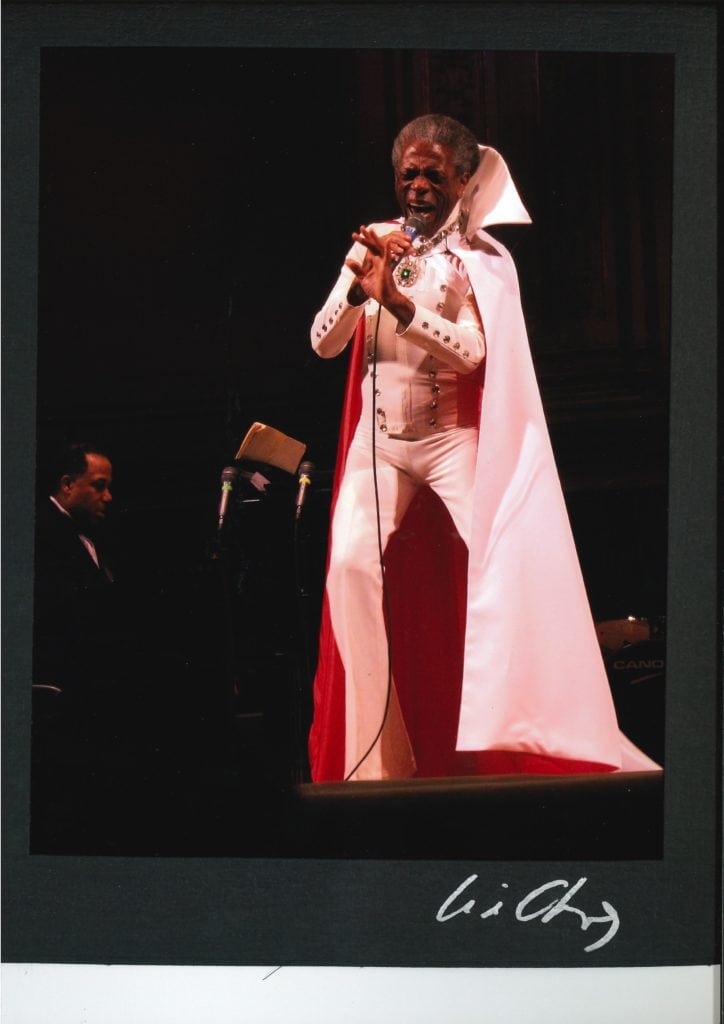

THE WIZ on Broadway

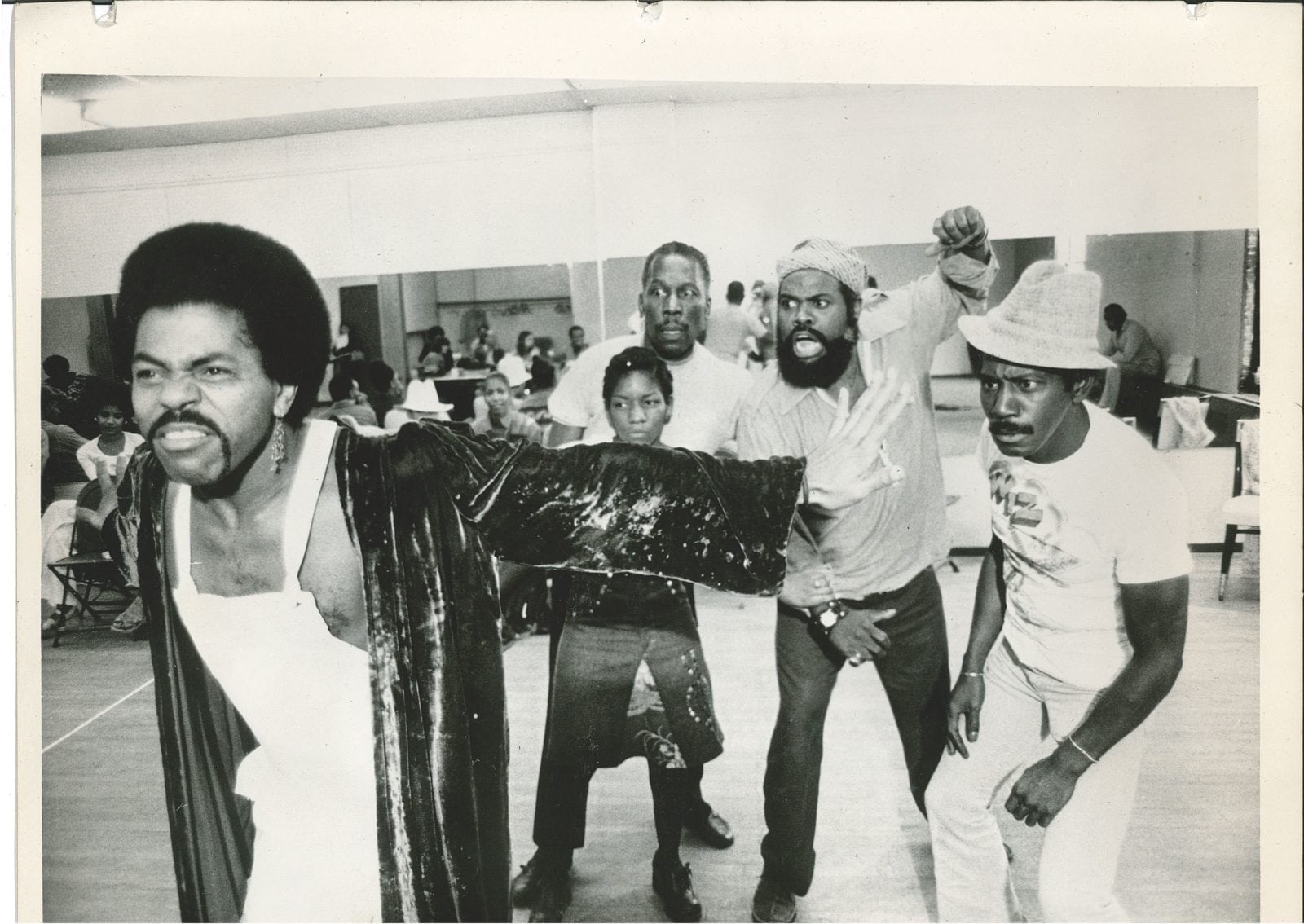

Rehearsing

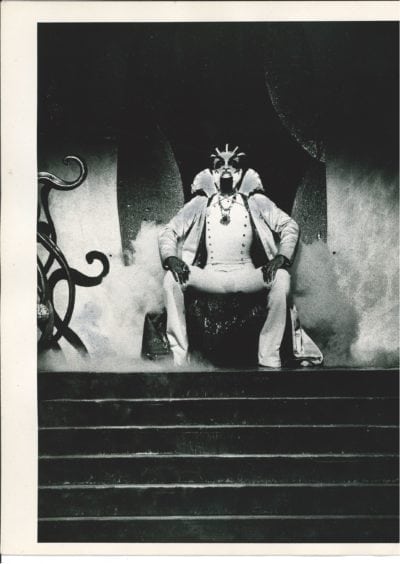

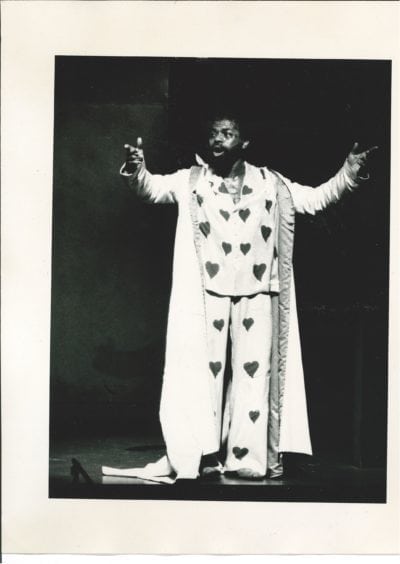

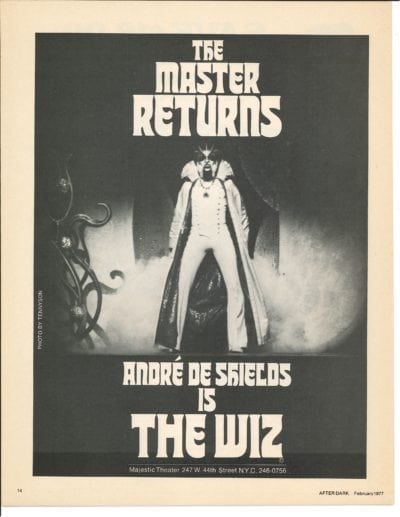

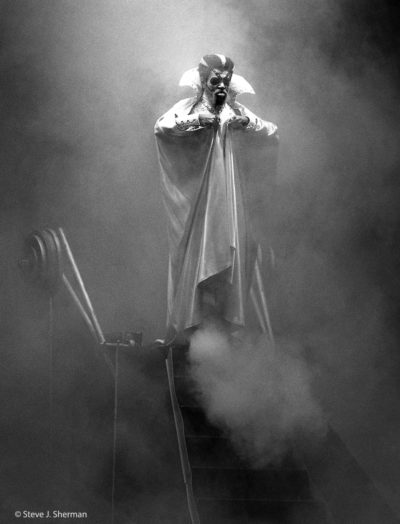

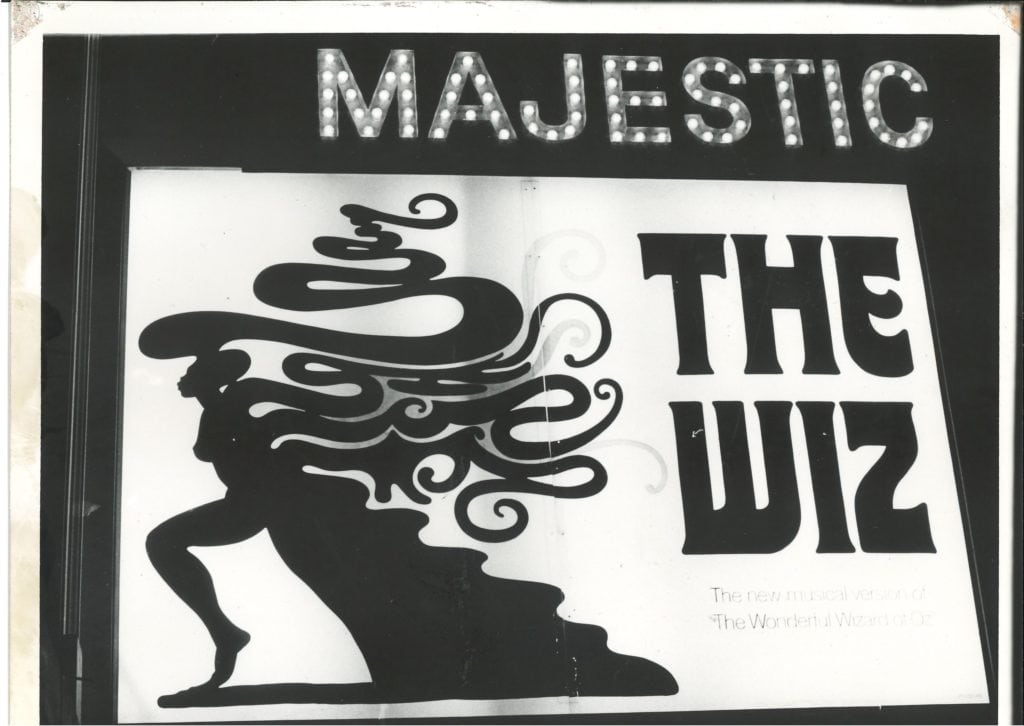

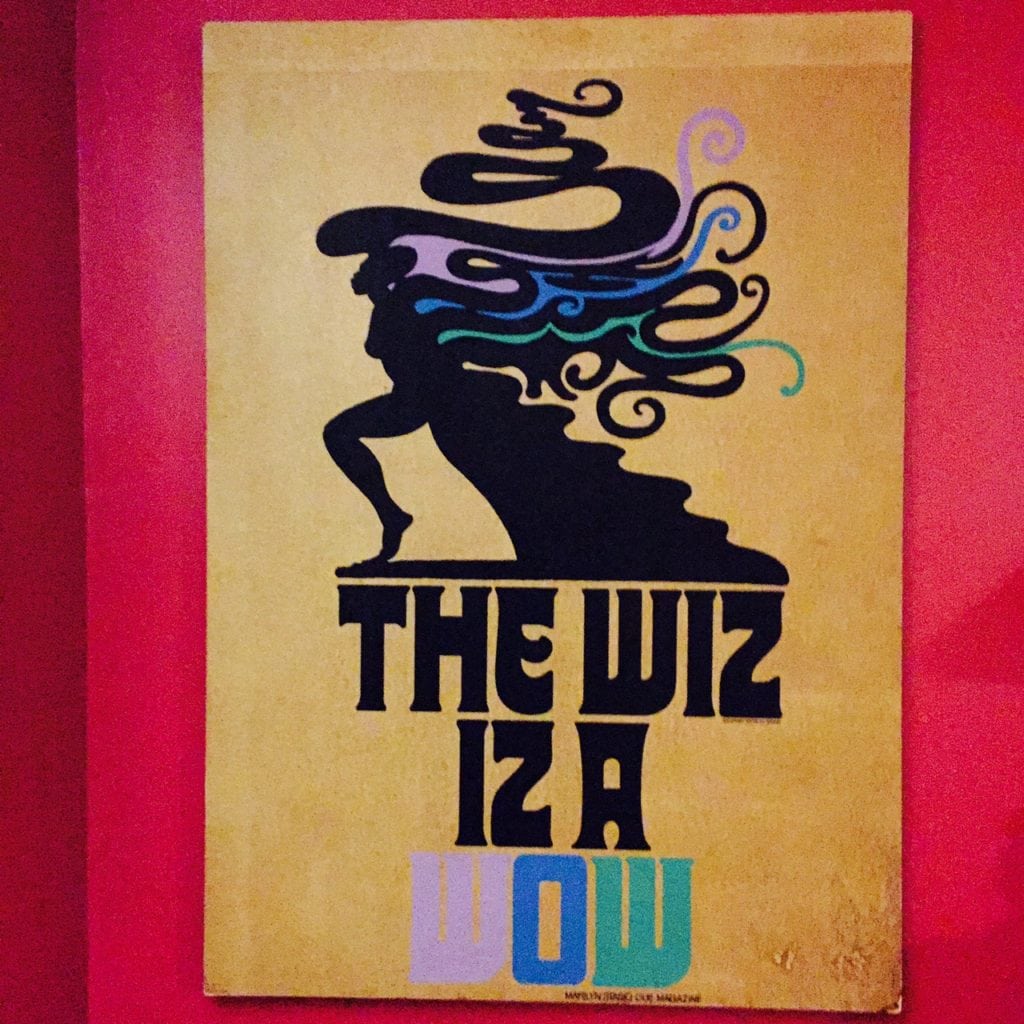

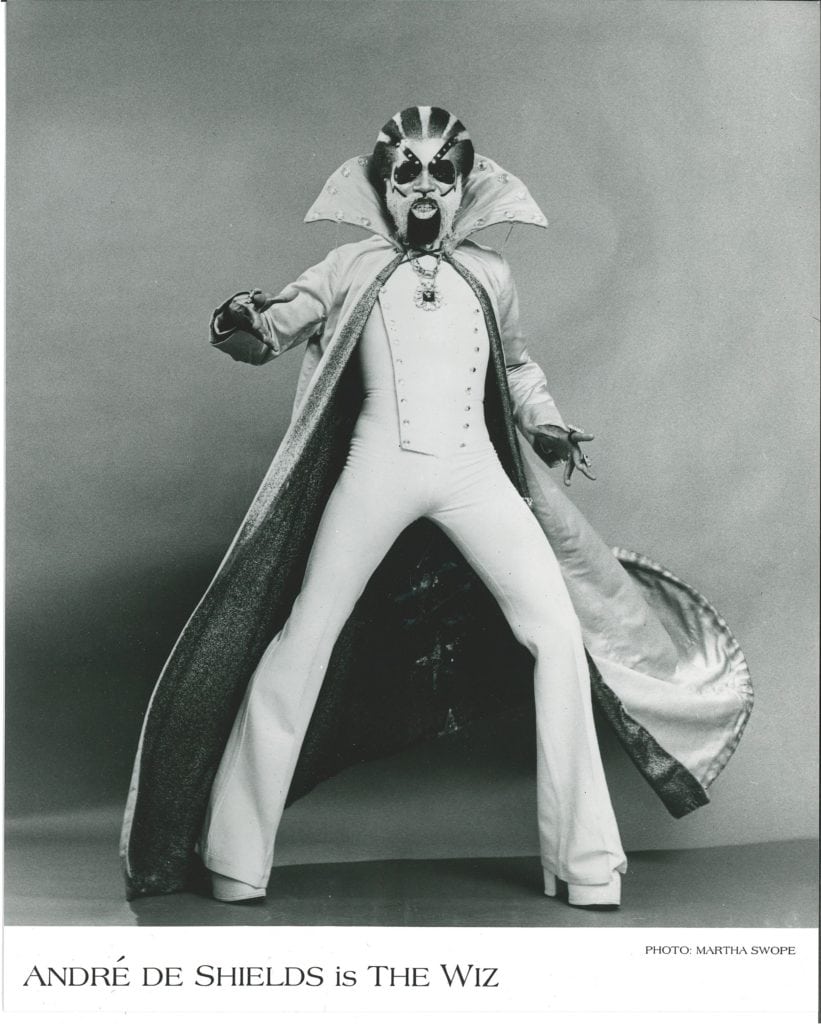

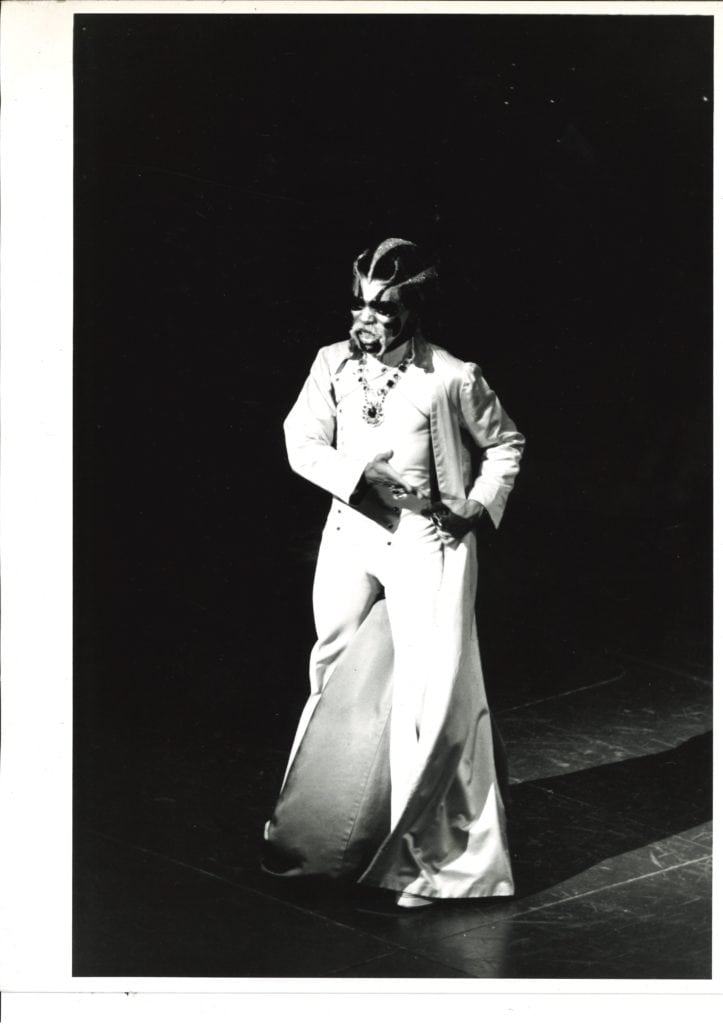

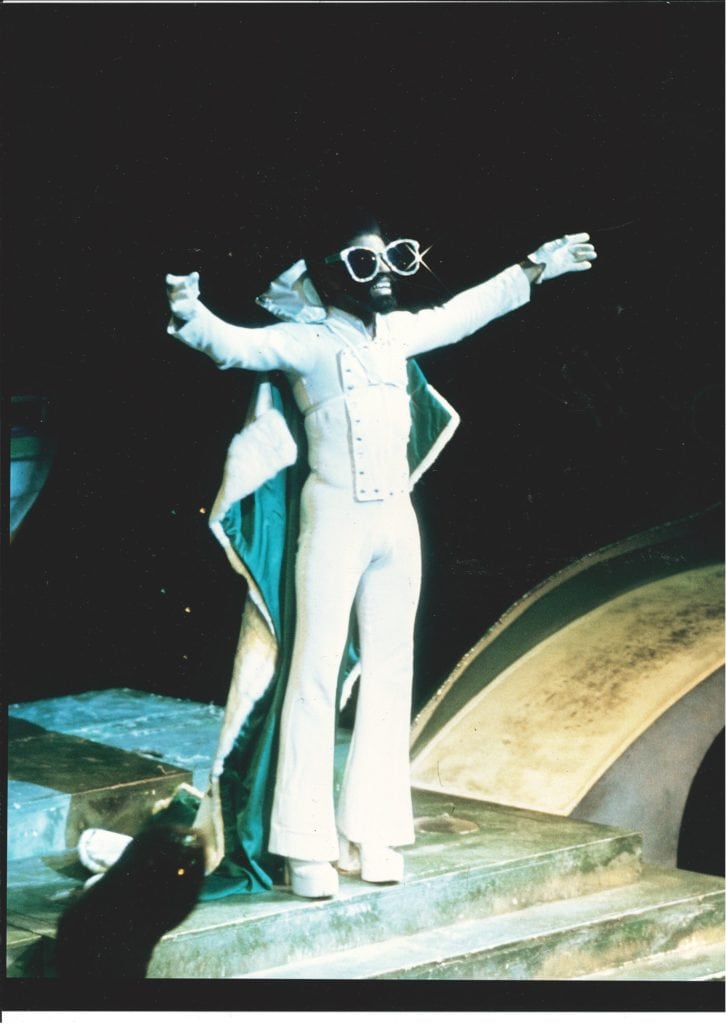

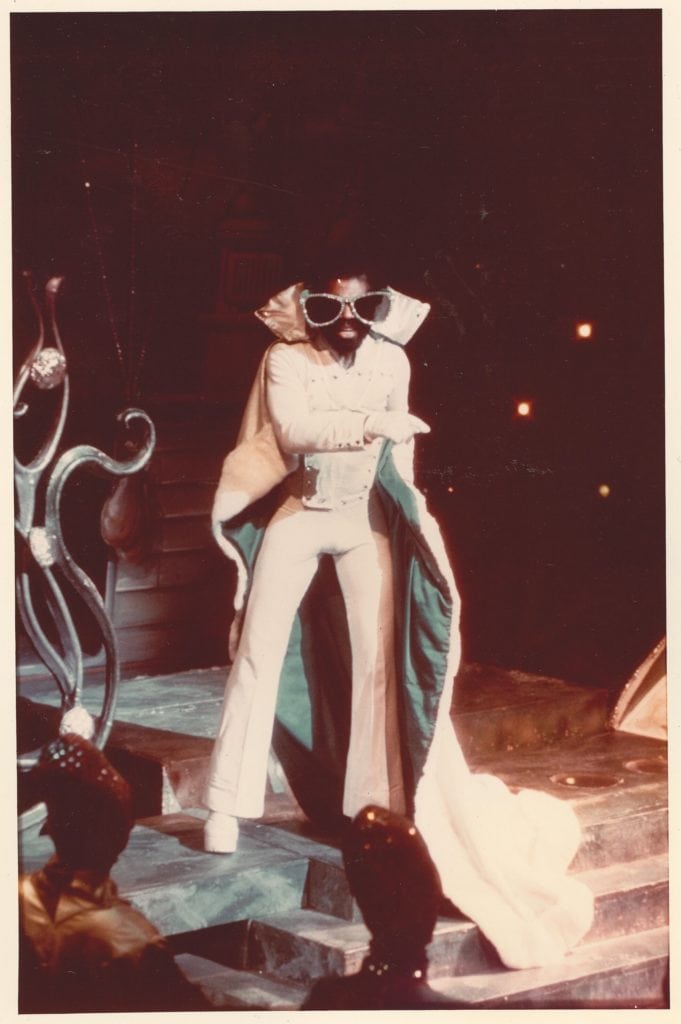

These photographs are from the 1975 production that opened at the Majestic Theater.

Photo: Martha Swope

Photos: Jeffrey Tennyson

Photos: Robert Torres

Photos: Roy Blakey

Photos: Ken Howard

Photos © Steve J. Sherman

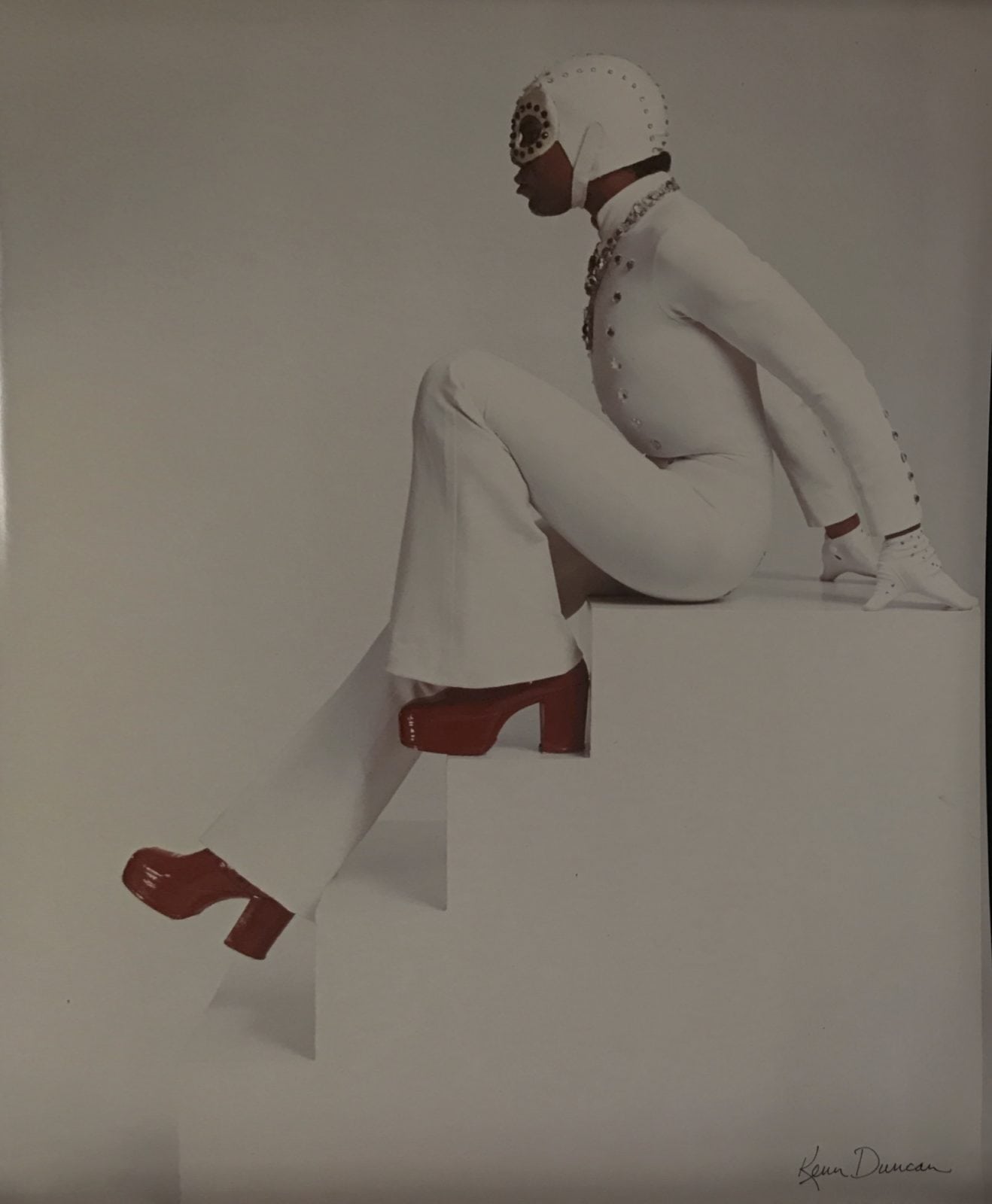

Photo: Ken Duncan for his book, The Red Shoes

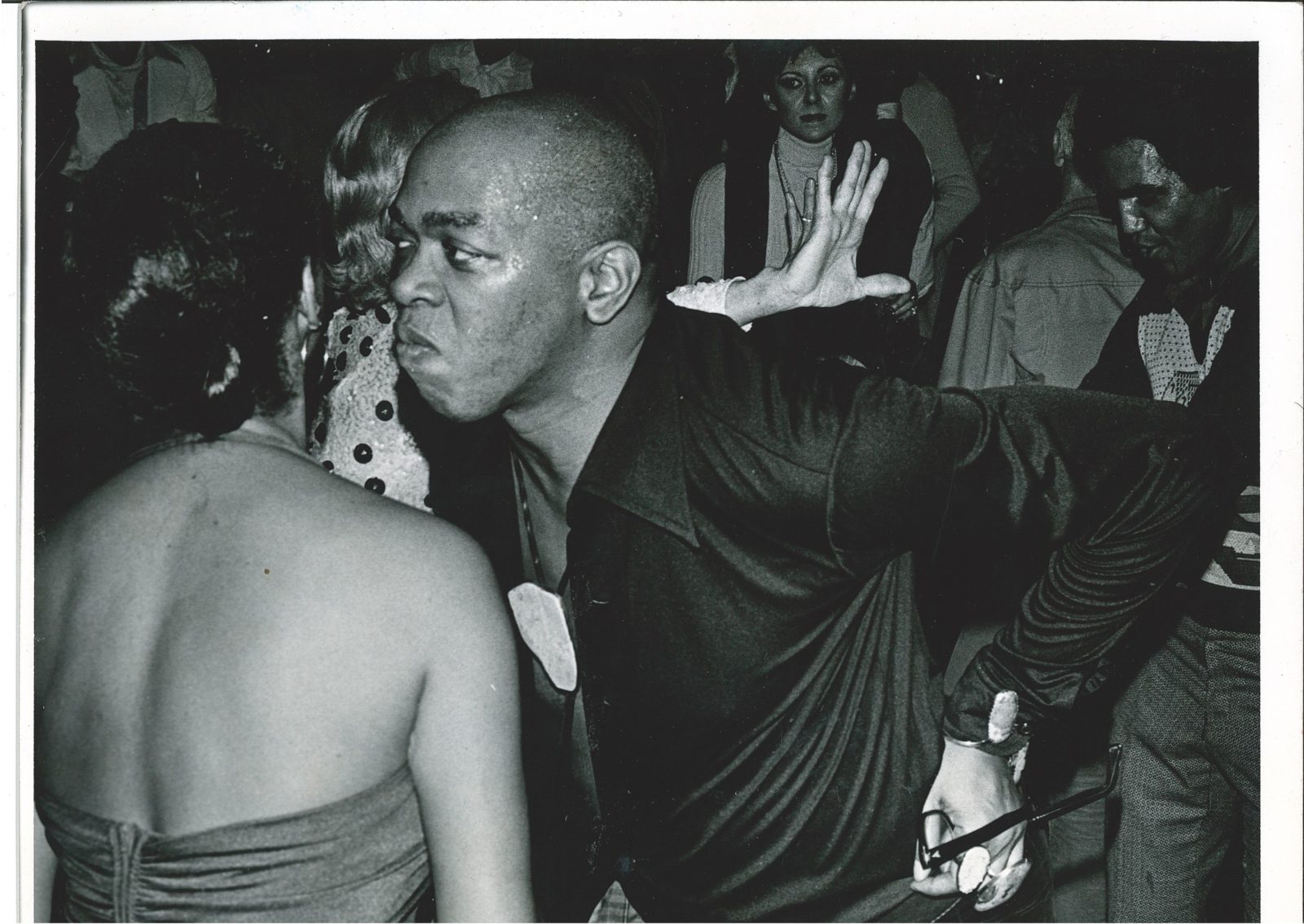

One Year Anniversary Party

Geoffrey Holder and Carmen de Lavallade hold court at 12 West.

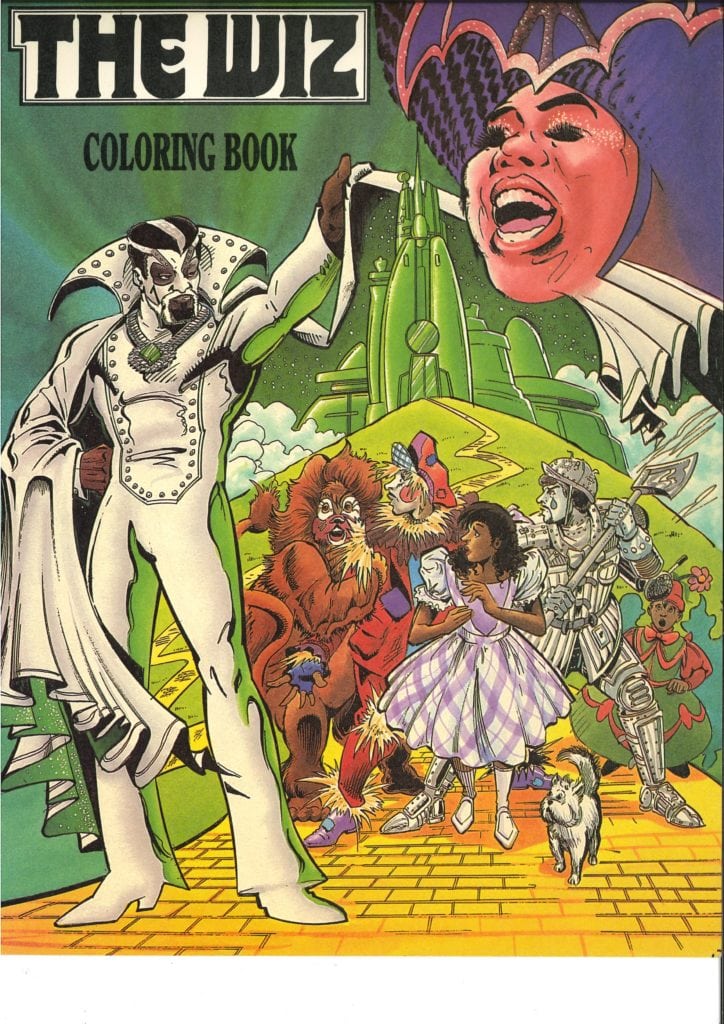

Commemorative Coloring Book

The Wiz in LA

The Wiz Legacy

EASIN’ ON DOWN THE YELLOW BRICK ROAD

A Black Man’s Journey to Oz

by André De Shields

This is a semi-sweet, bitter sweet, sometimes not so sweet, and yet ultimately sweet tale of the American Dream, once beyond grasping, then captured, lost and regained through the unique ability of the arts to transform the human condition. Where to begin? Where to begin? Where to begin? Ah, I believe it’s best to begin at the beginning.

The turn of the twentieth century in America was defined by the following two political bookends: the first, the 1897 Plessy v. Ferguson landmark decision handed down by the US Supreme Court, holding that racial segregation in issues vis-à-vis social equality was constitutional, paving the way for the repressive Jim Crow laws in the South, and the second, the founding in 1905 of the Niagara Movement by W. E. B. DuBois, in protest to the policy of accommodation to white society favored by Booker T. Washington. It was during this political atmosphere that L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published in 1900. Neither I, nor my mother or father had been born; yet this American fairy tale of adventure and wanderlust would become a symbol of self-determination in the life of this writer, born to Mary Elizabeth Gunther and John Edward De Shields on January 12, 1946, one year prior to Jackie Robinson’s shattering baseball precedence, when Branch Rickey, then president of the Brooklyn Dodgers, brought Robinson up to the Brooklyn club, making him the first Black American to play in big-league competition. Hindsight reveals that although a child of privilege, Baum shared a parallel ambition with me; he, the youngest of his parents’ seven children and I, the ninth of eleven, both dreamed of pursuing careers as actors.

I grew up, a child at risk, in the black inner city of Baltimore, Maryland. Now, hold your horses; before you jump to any conclusions, understand that I was well loved by both my parents and ten siblings. However, in terms of how the American Dream gets sliced and divvied up, my family qualified as impoverished. Impoverished children, particularly during their formative years, are at risk for self-contradiction, self-loathing, disenchantment with education, and they lack both self-fulfillment and self-belief. Subsisting on a diet of daily rejection and insecurity, children at risk nightmare about loss and inadequacy, instead of dreaming about hope and achievement. These children plan revenge on the world that relegates them to the margins of society, and perceive socialization as a form of defeat. Is there a silver lining on the cloud of despair that hovers over children at risk? Yes. It’s called cultural literacy. Hey, it’s not as highfalutin as it sounds. Check this out. Cultural literacy begins with believing in the possible, and that’s where the performing arts and, specifically, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz come into play.

At the approximate age of nine—so, this is 1954, the year the US Supreme Court decided the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, breaking with long tradition and unanimously overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson—I began to earn some pennies. Neighbors in my community—predominantly mothers who worked all day as domestics in the homes of the well to do—would not, at day’s end, have sufficient time to achieve every errand that needed running. They were busy keeping their own body and soul together. So, I would run errands for them, and, in return, earn a penny or two. I would save my pennies, and by week’s end, I would have saved enough pennies—twenty-five, thirty-five cents—to attend the local picture show. In those days, movies ran continuously from nine in the morning to nine at night. And that’s how I would spend my Saturdays . . . at the movies (feature films) that came packaged with coming attractions (trailers), newsreels (synopses of current events) and funnies (cartoons). The reigning champion at that time was The Space Adventures of Flash Gordon, a movie serial, based on a 1934 comic strip about a heroic earthling who avenged the universe against various nefarious villains. Of course, this was pure unadulterated indulgence in fantasy to escape the reality of the ghetto and its disproportionate neglect by city, state and federal government. Moreover, my identifying with the serial’s arch villain, Ming the Merciless, who commanded magic—he could shoot electricity from his extraordinarily long finger nails, and had access to advanced technology (the universally feared death ray)—was vindication from the harassment I frequently experienced at the hands of school bullies.

Hang with me now. By 1939, L. Frank Baum’s children’s novel had undergone its own transformation; the titled was shortened to The Wizard of Oz, and it was now a film, directed by Victor Fleming and starring Judy Garland. The film version quickly became a cultural icon and the universal archetype of cautionary tales about self-contradiction, self-fulfillment and self-belief.

One fateful Saturday at the movies, the feature film was The Wizard of Oz. By its fantastic title, my nine-year-old brain could only envision a movie similar to Flash Gordon, and that the titular character was yet another powering mongering invincible to whom I could relate. Can you imagine my amazement, upon realizing that not only was the wizard of the story not a villain, but that I would end up identifying with its young heroine, Dorothy? There I was, emotionally porous, psychologically impressionable, perched capriciously on the precipice of cultural literacy. Please forgive my alliterative pedantry, but a momentous occasion such as this requires waxing poetic. I was about to experience Oz Epiphany #1.

Fairy tales are necessary to cultural literacy; they reinterpret the past and visualize the future, crucial ingredients for the healthy progress of any all children. At my first viewing of The Wizard of Oz, I was able on the one hand to ascribe meaning to my young past in terms other than deficient, inadequate and lacking; while on the other hand create a positive mental image of my future, all due to the artistic literacy of that film. I saw myself reflected in the character of Dorothy, certainly not in gender, but in her meager environment. Dorothy was an orphan being reared by her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em, poor farmers trying to eke out a living from the vast, flat dry Kansas prairie that stretched endlessly to a gray and somber horizon. Her only friend and sole source of happiness was a little black dog, named Toto. Is this not the very image of youthful alienation from the American Dream? That was a palpable connection for me. Next, by natural disaster, Dorothy was transported to Oz, a land the opposite exact of her dreary home. And where did Oz exist? Why, somewhere over the rainbow, of course. The image of the rainbow has always, continues to and will forever conjure the idea of unconditional love, compassion and consciousness of the divine—those values that seem to go missing in our daily lives. Is this not the pot of gold waiting at its end?

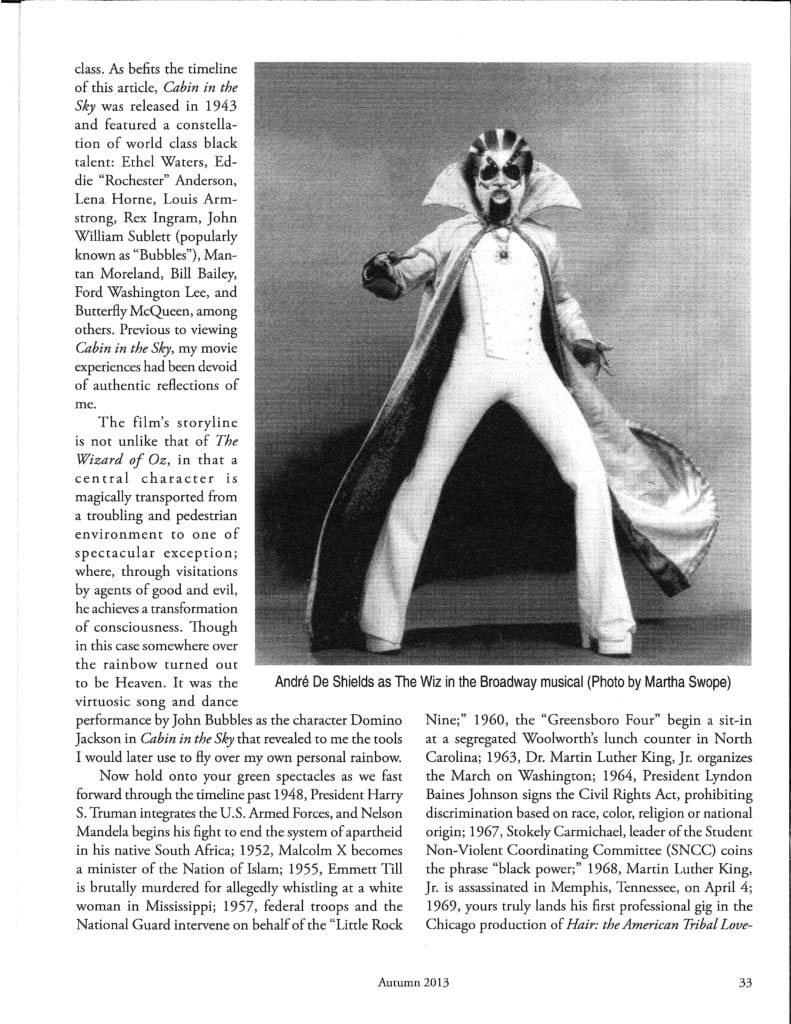

I would be remiss if I did not mention the other equally significant film that played an epiphanic role in placing me on the journey to my bliss: Cabin in the Sky, directed by Vincente Minnelli (Judy Garland’s second husband and father of Liza Minnelli) was an adult fairy tale told from the perspective of America’s Negro underclass. As befits the timeline of this article, Cabin in the Sky was released in 1943 and featured a constellation of world class black talent: Ethel Waters, Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Lena Horne, Louis Armstrong, Rex Ingram, John William Sublett (popularly known as “Bubbles”), Mantan Moreland, Bill Bailey, Ford Washington Lee and Butterfly McQueen, among others. Previous to viewing Cabin in the Sky, my movie experiences had been devoid of authentic reflections of me.

The film’s story line is not unlike that of The Wizard of Oz, in that, a central character is magically transported from a troubling and pedestrian environment to one of spectacular exception; where, through visitations by agents of good and evil, he achieves a transformation of consciousness. Though in this case somewhere over the rainbow turned out to be Heaven. It was the virtuosic song and dance performance by John Bubbles as the character Domino Jackson in Cabin in the Sky that revealed to me the tools I would later use to fly over my own personal rainbow.

Now hold onto your green spectacles as we fast forward through the timeline past 1948, President Harry S. Truman integrates the US Armed Forces, and Nelson Mandela begins his fight to end the system of apartheid in his native South Africa; 1952, Malcolm X becomes a minister of the Nation of Islam; 1955, Emmett Till is brutally murdered for allegedly whistling at a white woman in Mississippi; 1957, federal troops and the National Guard intervene on behalf of the “Little Rock Nine;” 1960, the “Greensboro Four” begin a sit-in at a segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in North Carolina; 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. organizes the March on Washington; 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act, prohibiting discrimination based on race, color, religion or national origin; 1967, Stokely Carmichael, leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) coins the phrase “black power;” 1968, Martin Luther King is assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4; 1969, yours truly lands his first professional gig in the Chicago production of Hair: the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical. It took a long time coming, but a change had to come.

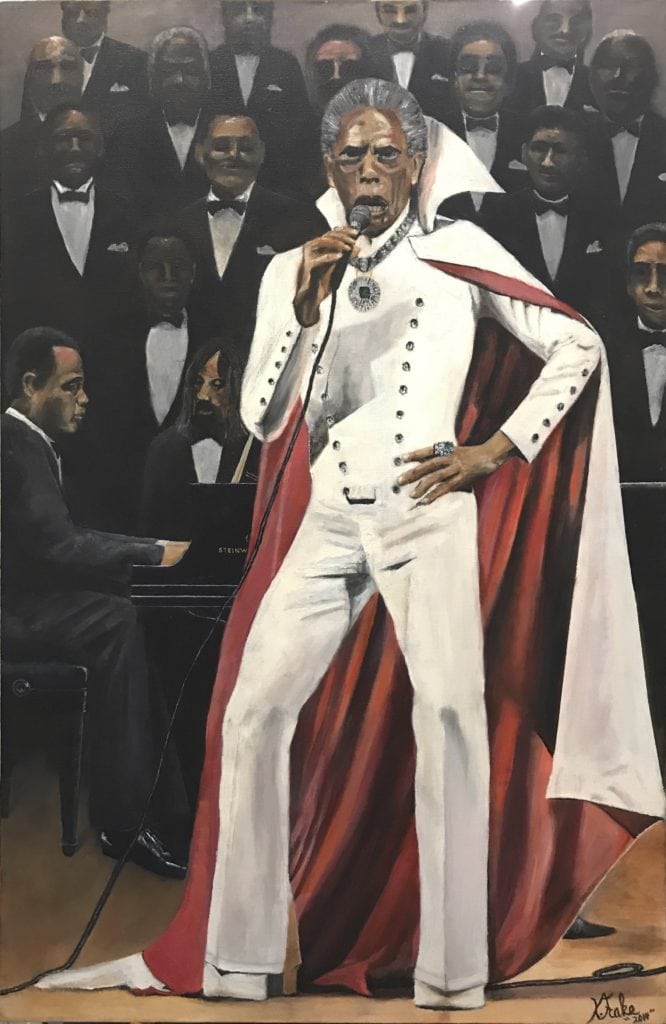

The musical Hair marked the beginning of a series of events that brought me to New York in the winter of 1973. By the summer of 1974 I had auditioned for and won the title role in a new musical destined for Broadway, The Wiz. It does not require rocket science to surmise that this title was yet another diminutive of Baum’s original The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Only this time producer Ken Harper sought to retell Baum’s fairy tale in the context of African American culture. One other essential element was changed: when Dorothy is taken up by a tornado in The Wiz (a cyclone in the original), and deposited in Oz, there are no doppelgangers for the community of people she knew in Kansas. When Dorothy meets the Scarecrow, the Tin Man, the Lion, the witches and, finally, the wizard, they are all new personalities bearing no resemblance to anyone back home. In other words, Dorothy’s trip to Oz is no dream; it is real.

The Wiz provided an opportunity for African American artists to bring a sui generis perspective to a universally known and loved tradition. Such favorable conditions had not existed since the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and ‘30s, when following WW I African Americans migrated in tremendous numbers from the agrarian South to the industrial North, initiating a blossoming of a new black cultural identity expressed in a potent convergence of literary, artistic and intellectual endeavors. Yet the battle for Civil Rights so bravely fought during the 1960s by the likes of Medgar Evers, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bayard Rustin and Marie Foster, to name a few, fertilized the cultural soil of America in a comparable fashion. The bold, innovative and soulful sensibilities of the creators of The Wiz heralded what could be considered a second renaissance in Black arts. And therein lay a profound conundrum, which many doubted could be overcome by the nascent revolution in American performing arts fomented by the advent of The Wiz.

In spite of the show’s stellar cast and exceptional production values, the initial critical response from New York reviewers was chilly, and occasionally racial in overtones. To be fair the out-of-town tryout was received enthusiastically in Baltimore, Detroit and Philadelphia, three cities with large, if not predominantly, African American populations. It was a particularly fulfilling experience for me that the production opened on October 21, 1974 at the Morris A. Mechanic Theatre in Baltimore, Maryland because that is my hometown. And the family and friends responded accordingly, filling the theatre to capacity. On one superlatively happy occasion, the entire cast arrived at my family’s house right smack in the middle of the ghetto for a home cooked meal. The attached row house—typical to Baltimore—was too small to hold all the guests; so, we spilled out onto the street with plates in hand; as my mother, Mary Elizabeth, and my sister, Mary Gloria turned out a soul food feast that became the talk of the neighborhood.

The show went on to play Detroit’s Fisher Theatre in November 1974, and Philadelphia’s Forrest Theatre in December 1974. But when The Wiz opened at Broadway’s Majestic Theatre on January 5, 1975, it was a completely different situation. With discouraging reviews and little advance sale, the cast experienced the irony of ironies: the closing notice was posted on opening night. Nonetheless, fiercely positive word of mouth combined with an aggressive and innovative television campaign saved the day, and “The Super Soul Musical” went on to make Broadway history, winning seven Tony Awards, including Best Musical, and securing a foothold on the Great White Way for future all-black casts. In this writer’s opinion, that miraculous turnabout of circumstances should have won for The Wiz status in the canon of Classic American Musicals. Additionally, I believe that status would have eventually been achieved if not for the ill conceived film version directed by Sidney Lumet, and the unfortunate timing of its release in 1978.

Still, after proving its merit against all odds, The Wiz settled in for an open end run, and on May 25, 1977, the production relocated from the Majestic Theatre—making way for The Phantom of the Opera—to the Broadway Theatre. In 1976, inspired by guidance from Geoffrey Holder, I joined the first national tour of The Wiz. In Detroit Geoffrey, who began as costume designer, inherited the position of director, after being vacated by Gilbert Moses. It was Geoffrey’s masterful people skills and embrace of magical realism that metamorphosed The Wiz from caterpillar to butterfly. Talk of a film version of the Broadway musical was already in the wind. Not only would the tour establish national recognition for my work, it also would make its first stop for six months in Los Angeles, followed by San Francisco and Chicago. It was during the run in Los Angeles that it was revealed how few members of the Broadway show would end up in the film. When you hear stories about performers paying dues or serving time in the trenches, it is this sort of disappointment that thickens the skin. It also is this cast of the die that reminds you: yours is a labor of love; if your toil does not make your heart sing, then your effort is misspent. Only Ted Ross and Mabel King, the Cowardly Lion and the Evilene, the Wicked Witch of the West respectively, would reprise their roles in the film.

I returned to the Broadway production of The Wiz in February 1977. By then, it was a fait accompli that Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Nipsey Russell, Thelma Carpenter and Richard Pryor would star in the film version of The Wiz. The resulting film was a critical and commercial failure. Casting Pryor in the role of the wizard meant the character would neither sing nor dance, thereby eliminating elements essential to his Broadway counterpart. The book by William F. Brown that faithfully followed Baum’s original story line was wholly abandoned for a Joel Schumacher screenplay that placed the entire action of the narrative in New York City. Perhaps the most egregious license was the casting of thirty-three year old Diana Ross as Dorothy, turning the character’s dilemma into one of a twenty-four year old schoolteacher who had yet to travel outside of her Harlem neighborhood, and who must overcome a case of arrested development. When at the heart of the fairy tale is the universal lesson learned by a little girl from the desolate plains of the American heartland that there is no place like home. The saving grace of the film was the transcendent performance of Lena Horne—yes, the same Lena Horne who portrayed femme fatale Georgia Brown in Cabin in the Sky—as Glinda, the Good Witch of the South. The plot thickens.

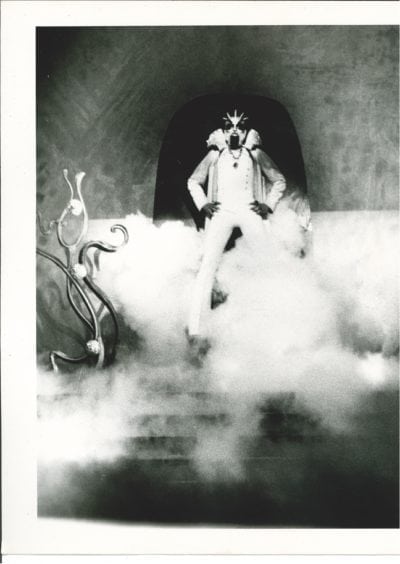

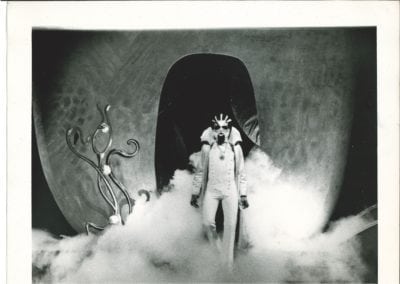

On the evening of Wednesday, July 13, 1977, I had barely made my entrance as Mr. Wiz, down a steep flight of seventeen stairs, wearing five-inch platform shoes, through a voluminous cloud of white smoke, when at 8:37 PM a strike of lightening caused a power failure in New York City that darkened the entire borough of Manhattan. At that same moment the theatrical lights in the Broadway Theatre went out, evoking a gasp from the audience. Almost as quickly, the emergency generators kicked in, and the performance continued under the ghostly glare of giant incandescent bulbs. Once we were informed of the nature of the event, the cast was instructed by stage management to cease performing. The theatre had become a kind of Camp Broadway as the cast shared stories of our varied lives with the audience, while we all waited for information regarding the situation on the outside. Ultimately everyone was instructed how to safely leave the theatre and reach our individual destinations. The combination of the news about the film and the temporary suspending of the play left me with the unsettling feeling that I had become the Wizard of Odd. You are now familiar with the episode I dubbed Oz Epiphany #2.

Shortly thereafter, in August 1977, I terminated my contract. 1978 saw the release of the film, and on January 28, 1979, after 1,672 performances The Wiz closed on Broadway. To be sure there were subsequent productions of The Wiz, domestic and international, but not one of them ever equaled, much less surpassed, the social significance and timeless elegance of the prototype. Not even the 1992 revival, helmed by George Faison, the Tony Award winning choreographer of the 1975 production, and starring the original Dorothy, Stephanie Mills and myself, managed to restore the musical’s pedigree. For since then, when The Wiz was mentioned, only recollection of the film version’s overwhelming miscarriage came to mind.

These many years later The Wiz has suffered other ravages. Only a small portion remains of the original family of artists who in 1975 created Broadway history. The following individuals have since become ancestors: Ken Harper (producer), Charlie Smalls (composer), Charlie Coleman (conductor), Charles Blackwell (production stage manager), Tiger Haynes (the Tin Man), Ted Ross (the Cowardly Lion), Mabel King (Evilene, the Wicked Witch of the West), Clarice Taylor (Addeperle, the Good Witch of the North), Tasha Thomas (Aunt Em) and a host of singers and dancers who were the spine of the production.

I have a dream of resuscitating The Wiz, removing its tarnish, repairing its reputation, refurbishing its luster, restoring its former glory and reinstating it in the canon of American musical literature. It is a dream that I carry close to my vest lest it be sullied by the missteps of the well intended. Alas, good things tend to come to those who wait. My waiting was rewarded when on July 11, 2011, I received an invitation by way of my publicist, Merle Frimark, to attend the 34th annual All Things Oz Festival in Chittenango, New York, the birthplace of L. Frank Baum. The invitation came from Marc Baum, no relation to L. Frank Baum, and proved to be a transformative shot from the blue, not quite the perfect storm that carried Dorothy to Oz, but definitely an event that once again firmly placed my feet on the Yellow Brick Road.

Marc’s invitation described Chittenango as a small suburb of Syracuse, NY that annually hosted the Oz-Stravaganza, a festival to celebrate the life and work of L. Frank Baum. I was about to experience Oz Epiphany # 3 as the special guest for the weekend of June 1 – 3, 2012, when 20,000 Oz aficionados would descend upon Chittenango for events that included a parade, autograph signing sessions and Oz related interviews. Marc wrote: “Having played the part of the Wizard on Broadway in The Wiz, André is part of the Oz Universe, and our fans would love to get a chance to meet him.” Merle and I arrived on Wednesday, May 30 to get settled and be treated to local cuisine. We became acquainted with members of the Executive Committee over a round of “fribbles”—a frosty concoction of ice cream, soda, whipped cream, hot chocolate nuts and fruit, served in the tallest parfait glass I have ever seen, and accompanied with a nine inch dessert spoon. Our reception was greater than either of us could have ever imagined. To my surprise and pleasure both the visitors to the festival and the local media took full advantage of my participation.

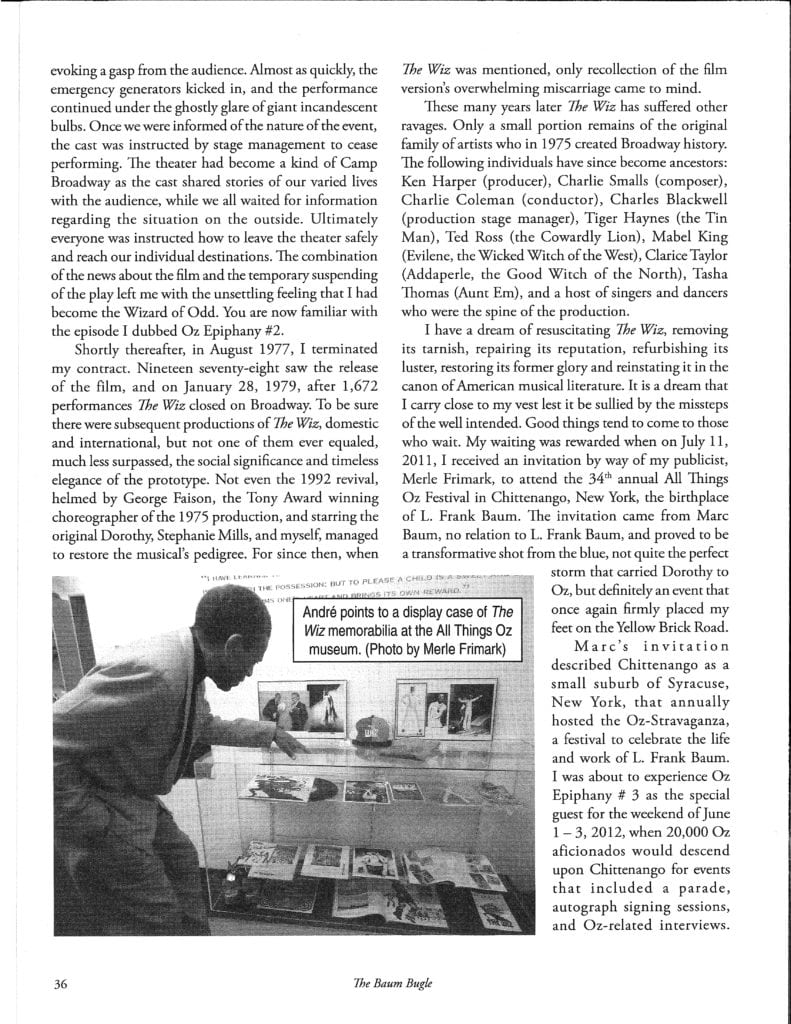

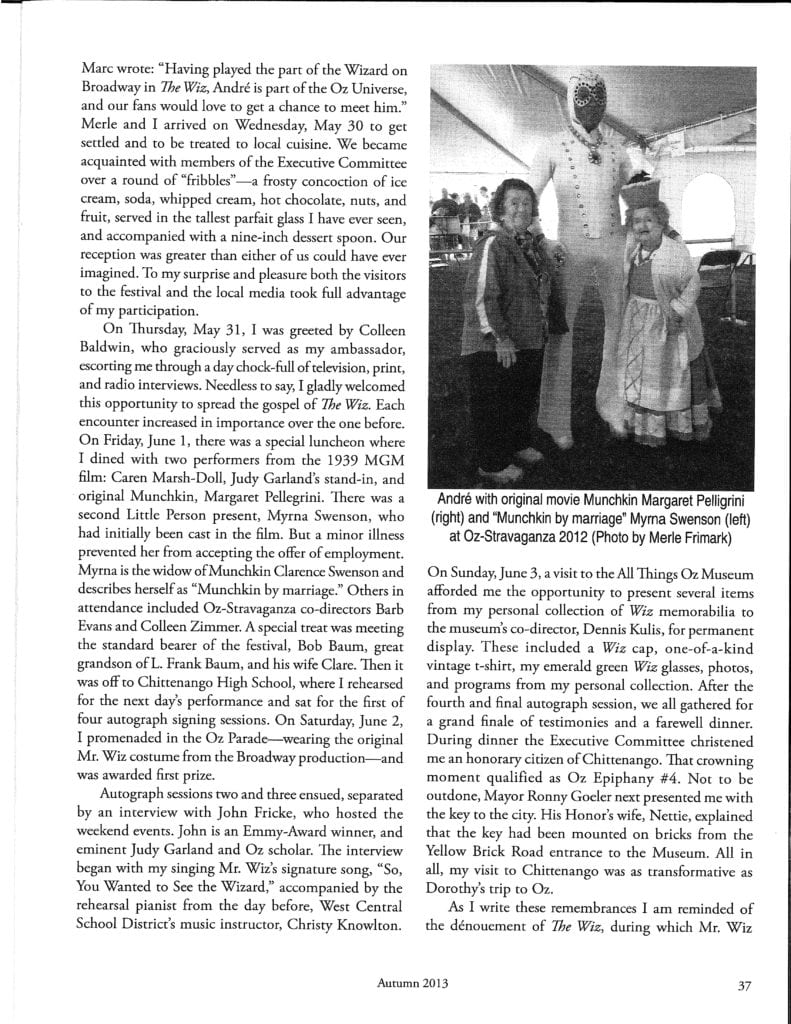

On Thursday, May 31, I was greeted by Colleen Baldwin, who graciously served as my ambassador, escorting me through a day chockfull of television, print and radio interviews. Needless to say, I gladly welcomed this opportunity to spread the gospel of The Wiz. Each encounter increased in importance over the one before. On Friday, June 1, there was a special luncheon where I dined with two performers from the 1939 MGM film: Karen Marsh Doll, Judy Garland’s standby, and original Munchkin, Margaret Pellegrini. There was a second Little Person present, Myrna Swenson, who had initially been cast in the film. But a minor illness prevented her from accepting the offer of employment. Myrna is the widow of Munchkin Clarence Swenson, and describes herself as Munchkin by marriage. Others in attendance included Oz-Stravaganza co-directors Barb Evans and Colleen Zimmer. A special treat was meeting the standard bearer of the festival, Bob Baum, great grandson of L. Frank Baum, and his wife Clare. Then it was off to Chittenango High School, where I rehearsed for the next day’s performance, and sat for the first of four autograph signing sessions. On Saturday, June 2, I promenaded in the Oz Parade—wearing the original Mr. Wiz costume from the Broadway production—and was awarded first prize. Autograph sessions two and three ensued, separated by an interview with John Fricke, who hosted the weekend events. John is an Emmy Award winner, and eminent Judy Garland and Oz scholar. The interview began with my singing Mr. Wiz’s signature song, “So, You Wanted to See the Wizard,” accompanied by the rehearsal pianist from the day before, West Central School District’s music instructor, Christy Knowlton. On Sunday, June 3, a visit to the All Things Oz Museum afforded me the opportunity to present several items from my personal collection of Wiz memorabilia to the museum’s co-director, Dennis Kulis, for permanent display. After the fourth and final autograph session, we all gathered for a grand finale of testimonies and a farewell dinner. During dinner, the Executive Committee christened me an honorary Oz-Hole (citizen of Chittenango). That crowning moment qualified as Oz Epiphany #4. Not to be undone, Mayor Ronny Goeler next presented me with the key to the city. His honor’s wife, Nettie, explained that the key had been mounted on bricks from the Yellow Brick Road entrance to the Museum. All in all, my visit to Chittenango was as transformative as Dorothy’s trip to Oz.

As I write these remembrances I am reminded of the dénouement of The Wiz, during which Mr. Wiz is confronted by Dorothy and her three friends, who demand that he make good on his promise to equip the Scarecrow with brains, the Tin Man with a heart, the Lion with courage and Dorothy with a means to get home. I am also reminded of the little boy, who decades ago sat in that movie house and wondered about his brains, heart, courage and way home. When the Wizard gifts the Scarecrow with a diploma, it is merely a symbol of the intelligence he already possesses. Were it not for his lack of self-belief, the Scarecrow would have long ago been aware of his ability to think, reason, analyze and construe. Similarly, the Tin Man is indeed benevolent, sympathetic and kind-hearted. But for the lack of a recognizable symbol the Tin Man would not doubt that he has a heart, which is evidenced by the compassion he displays for his fellow seekers. The Lion certainly performs acts of bravery, yet he is missing a symbol of his valor. A badge of courage from the wizard does the trick, and rids the Lion of self-loathing. Of course Dorothy’s plight cannot be resolved by mere symbolism; hers is a philosophical journey for which the wizard has no solution in his bag of cunning deception. Her resolution calls for a deus ex machina, one as powerful as the disenchantment that brought her to Oz. And that power can only be found within. It is called self-determination. This very premise is expressed in the text of the Broadway musical, The Wiz. At the show’s end, Mr. Wiz, newly contrite, delivers a farewell sermon to the citizens of Emerald City, the essence of which is “You can’t know where you’re going, unless you know where you’re coming from.” As Dorothy forgives herself and gratefully acknowledges her humble beginnings, she finds the strength to will herself home. For that is where healing begins.

It has taken a lifetime to master the skill of self-determination. Moreover, I am confident of having arrived on the path to self-fulfillment, for I am no longer on the road of self-contradiction. And in no small way I owe this awareness to L. Frank Baum, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and my voyage of discovery at the Oz-Stravaganza. My heart swells with joy and the promise of future Oz Epiphanies.

And as for that dream of resurrecting The Wiz, Marc Baum and I are looking to the year 2015, which marks the fortieth anniversary of its Broadway opening. Does there exist a more appropriate place to resurrect The Wiz than Chittenango, the center of the Oz Universe? I don’t think so. And if there is, it must be somewhere over the rainbow. Not to worry; I’m sure to find it as I continue to Ease on Down the Yellow Brick Road.