Yes, designers get typecast, too.

Ending our third or fourth meeting for the set for a new Neil Simon play, Joe Mantello, the sharp and excellent director was frustrated with my struggles to come up with a set. He said at the top of the uptown subway stairs on Fiftieth & Broadway, “Oh, just do that thing you do!” and left me to ponder.

I knew what he meant. By that point in my career, there was something vaguely recognizable as a John Lee Beatty set — usually an architectural interior or a leafy exterior. Lest Joe appear harsh by his comment, I totally respected him for a keen theatrical eye. He may have realized that we had come to the end of finding anything else for the play, or may have acknowledged that I had indeed been hired to “do that thing you do.” I worked with him three or four more times after; he had a great eye for scenery and was a wonderful editor. We later collaborated on a revival of The Odd Couple (a classic old Upper West Side apartment) and Other Desert Cities ( a classic mid-century Palm Springs mansion) — two inviting and emotionally complex interiors.

But I realized I had been typecast — a double-edged sword. I was known for being good at something, and was hired often, but then I was considered for that one kind of thing alone, it seemed. I was like a character actor hired to do a certain thing. It was a bit dangerous to me as well, as I fell into feeling a certain something I had done before was expected of me. I was asked to do many more plays of a certain kind, and finally had to restrict how many ‘yummy interiors’ I was to do, and when I did them.

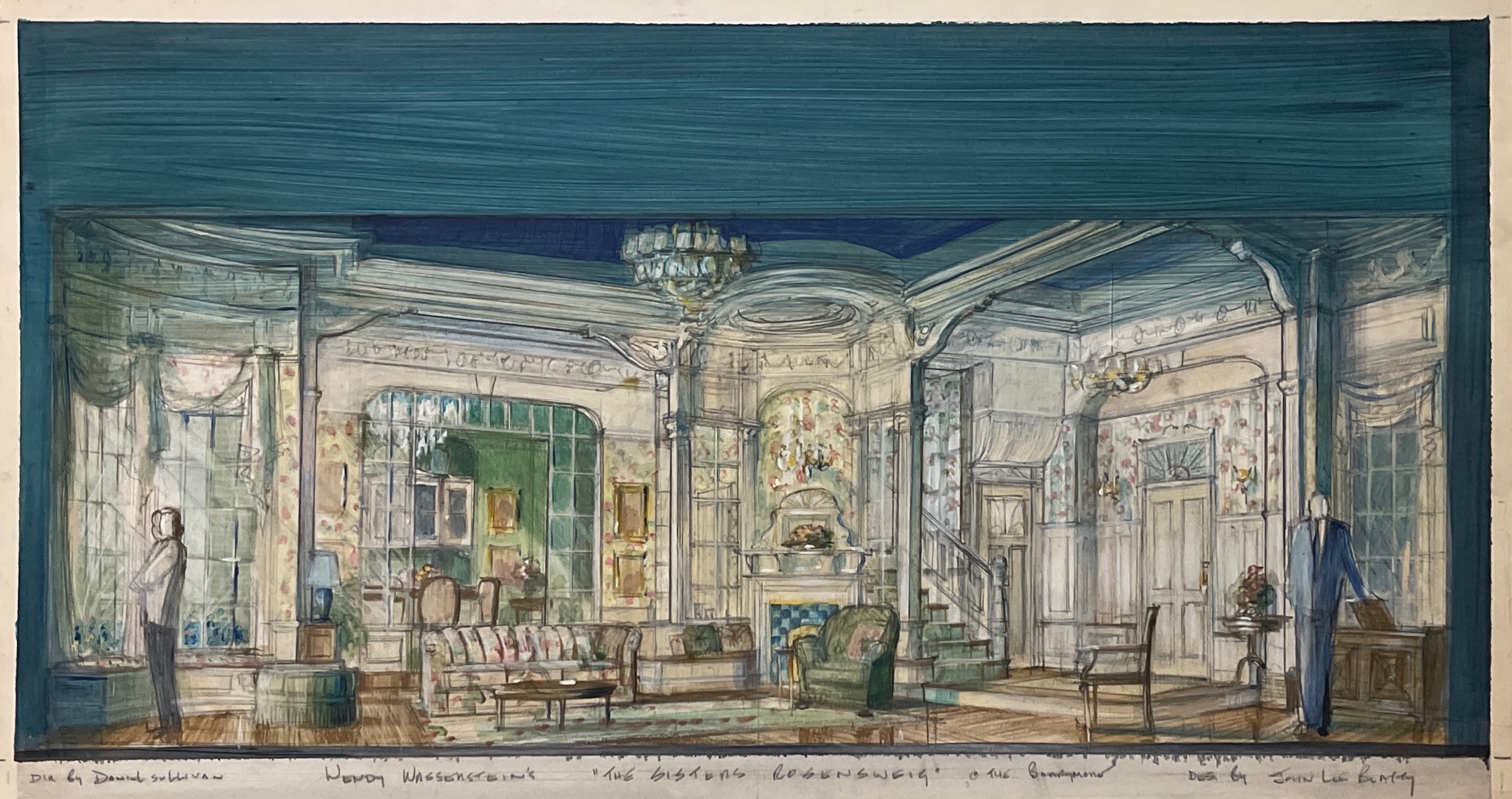

John is one of the few contemporary designers whose name is a brand name. When we think of a John Lee Beatty set, we usually think of a room, an interior-often richly appointed, immaculately laid out, tasteful, detailed and ever so slightly larger than life. And we think of the rooms beyond–the rooms we in the audience only catch glimpses of-the hallway, the offstage dining room, the upstairs bedrooms–all barely in the play, and all just as carefully designed and executed as the main setting. John, and perhaps this is also a 19th century trait, understands the life and history of a room, and therefore of a house and the people who inhabit it. It is INTERESTING that a man from California–the ultimate outdoor state–should be such a shrewd judge of the indoors. André Bishop, Artistic Director,

Lincoln Center Theater

Since some of my stage interiors seem so appealing, I am often asked to design home interiors, but I have no idea how to do ‘real’ interior decoration. Someone called me last month with that idea. I said no. I even had to have a designer friend help me in my own apartment. Even the restaurants I have designed required the owner to create a back story for me to function. I need an author. And maybe even a plot.

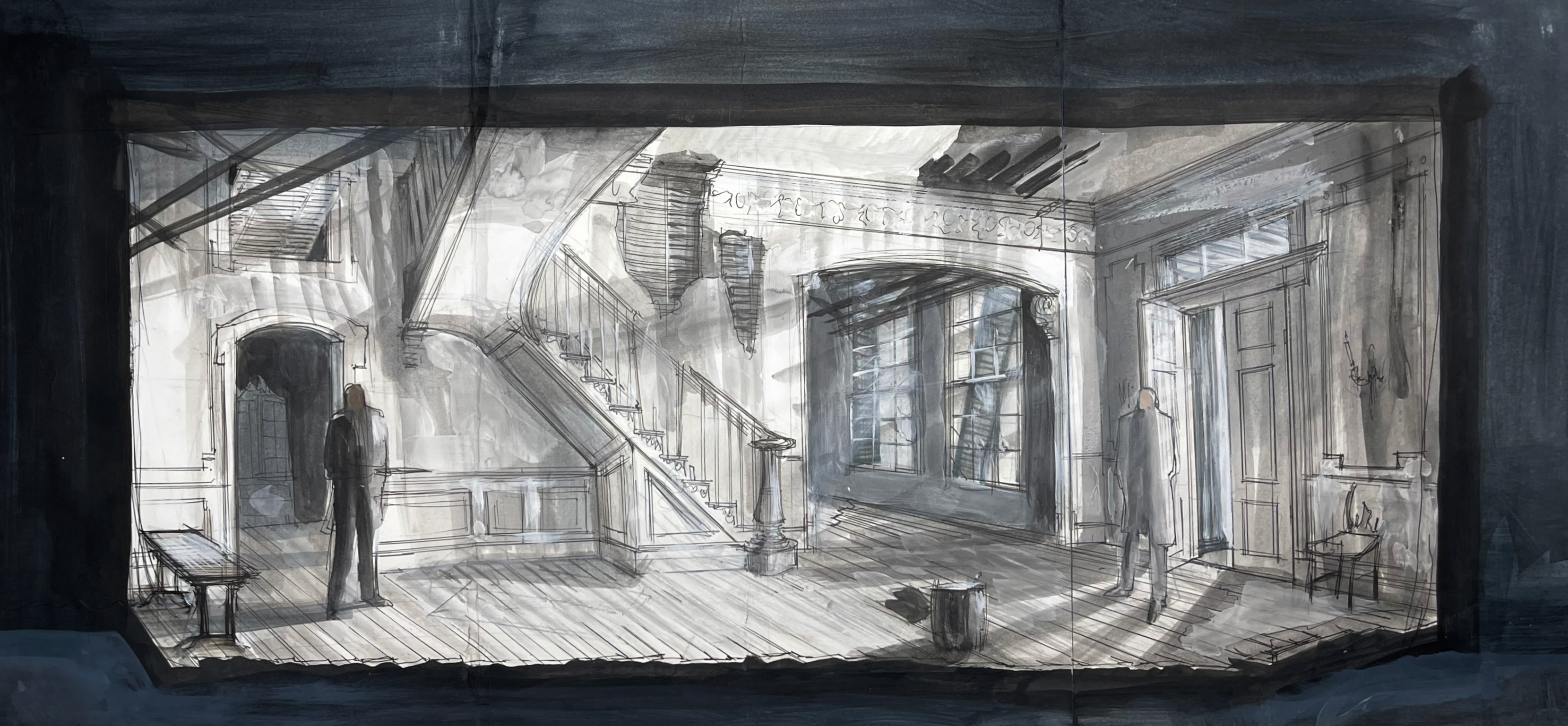

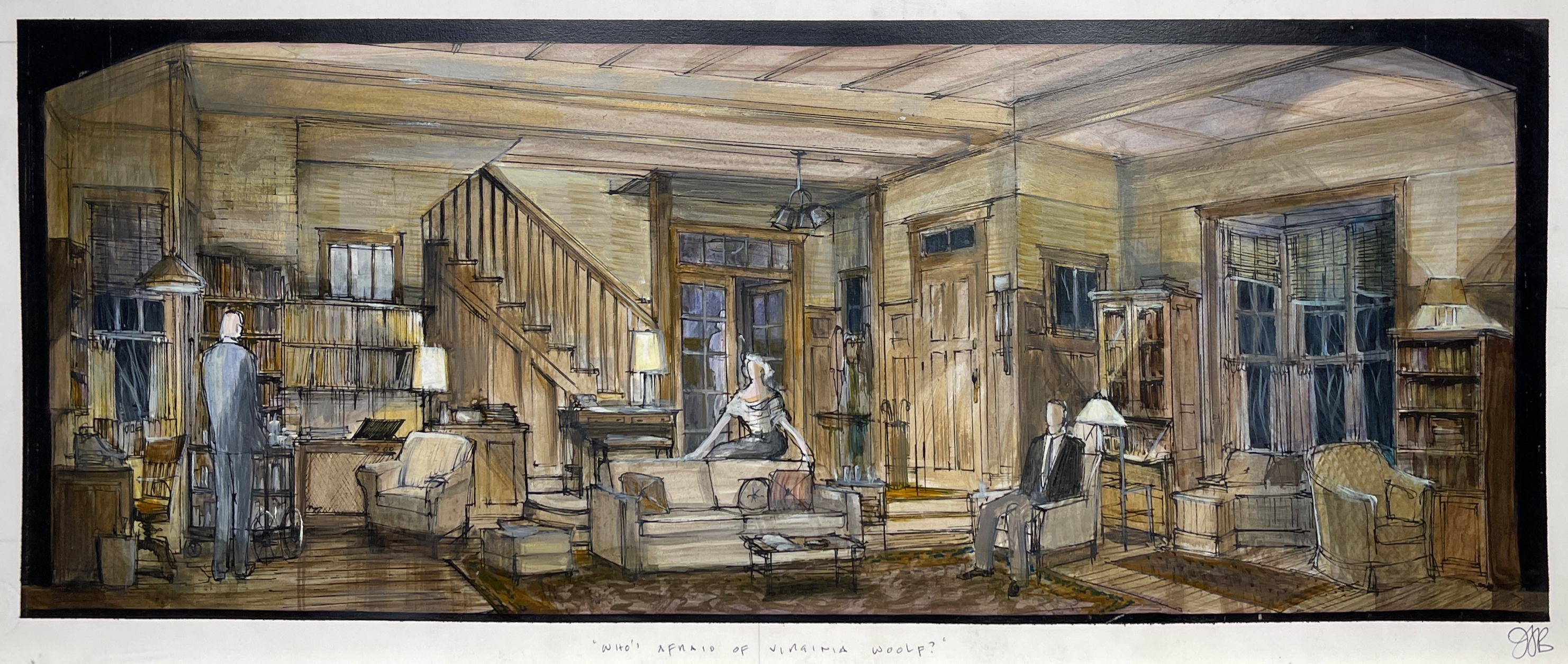

Yes, I became identified with ‘architecture porn’ or “yummy interiors where I just wanted to move in.” How I got to that point is not so mysterious, as I designed plays mostly, and most plays took place in interiors. In fact, there were many classic American plays that shared the classic formula: sofa, front door, window-to-street, staircase-up. Think of Life with Father all the way to Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

After designing so many American plays, I came to realize that our national preoccupation was real-estate. British plays were about class, our immigrant nation was more concerned with real estate. I once did an English play where the shocking statement was “I had sex with a plasterer!”—and the American version would be “I lost the house!” A Streetcar Named Desire and Death of a Salesman both hinge on the loss, or possible loss, of houses. Often an American audience will come to some conclusion about the meaning of the play by analyzing the real-estate presented to them.

Oddly, in musical theater my two mega-hits, Ain’t Misbehavin’ and CHICAGO were abstract to the extreme, almost modest. The complete opposite of what I was known for and most people completely forget that I did them. I have also done extremely minimal plays, but … again no one remembers.

I knew what director Joe Mantello meant that day. I remember an amused artistic director saying a visitor had entered his dark theater and asked how he had come to have a John Lee Beatty set, merely by looking at it in the ghost light. I do not know why this particular form of recognizable design comes out of me. I sometimes think it is like a voice—and I am a light baritone, with a warm timbre. I know that the rooms and gardens I design have an emotional quality to them, usually warm. And that my voice is an American voice. I have failed mightily at two chilly English plays about divorce. I was miscast.

I also realized that, by doing so many plays of one sort, with so many props, that I became associated with that kind of production, for better or worse. The audience, and the critics, came to expect a certain thing. I had to be careful, but really the assumption of what I would do was already in place.

I grew up in old houses and crawled around examining the floorboards and baseboards and stair railings. I was always interested in floorpans, and the human function of rooms, and how the people of the period used them. Director Doug Hughes was amused at my angry, flustered insistence that the set as described in the stage directions for The Whipping Man be re-conceived to conform to the functional layout of an 1850 house, not a 20th century one. To me it felt like a period play with a HGTV ‘open plan.’ And yes, that set had to have a front door, a sofa, a staircase, and a window to the street. But to me, extremely specific ones.

Once, after remounting a production of The Sisters Rosensweig together, the costume designer Jane Greenwood and I wandered the streets of Seattle, slightly tipsy from dinner, talking about our lives and careers, and I opened up to her about my typecasting. I shared how frustrated I was that another hot new designer (a Joe Mantello favorite) got all the imaginative and colorful shows to design, while I always got the ‘sofa and staircase’ plays. Jane opined cheerily that “__________, the hot designer, will come and go, but plays with sofas and staircases will last forever.” Jane, a wise lady of the theater as she is, turned out to be right on both fronts, because that designer no longer designs, and this very day I am designing yet another new play with a sofa and staircase. Oh, and a window to the street.

Jane and I followed Rosensweig (which of course had a sofa and staircase, but you already knew that) with smashingly successful revivals of The Heiress, A Delicate Balance, and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? All of which had … well, you know … and a lot of nice moulding and well-observed props. I hasten to add that I do not pull old designs out of my drawer, but start over every time, since sofas, staircases, and windows are not all the same. Not the same at all. Neither are ceilings.

I know that I imagine full rooms, or full exteriors in total. That’s how they come to me. I think that’s why nothing seems arbitrary. All the pieces connect. When imagining these worlds, I have to imagine them inhabited, with good actor entrances and exits, of course. There is always a sense of beyond and a beyond. My sets are often called ‘realistic,’ with which I quite disagree. First, they are theatrical constructs that always include the audience’s point of view. And even sets which function in a realistic manner have severe editing going on. I am designing a specific author’s fiction, not making a documentary. Even the Proof setting, the back porch of a professor’s house at the University of Chicago, which I admit was thoroughly researched, had a color scheme of only seven colors, taken from a favorite sweater of mine. I carefully eliminated all extruded plastic products lending to the air of autumnal romance.

What intrigues me is that one can create emotions by inanimate means, starting from the ground up, making a series of scenic choices. In the musical The Most Happy Fella the director Gerald Gutierrez and I played with winched moving scenery at different cues — of three moments of movement, two would make the audience cry, one would not — fascinating to us. There is a certain fascinating (to me) alchemy about what these physical ingredients can elicit in an audience and how they participate with the actors. Lanford Wilson realized it when giving me his Talley’s Folly script for the first time. The set description was “moonlight through broken shutters.” Not the ground plan. He trusted that I was going to design emotion.

I see that I am typecast like an actor, and I also elicit emotions as an actor does. I too, must get into the right emotional state in order to create my worlds of sofas and staircases.

Here is an article from the New York Times (August 4, 1991), Rooms With a View … of the Audience.

Here is another article from the New York Times (January 21, 2003), Lush, Plush or Seedy: Sets Filled With Power.