IN FLUX

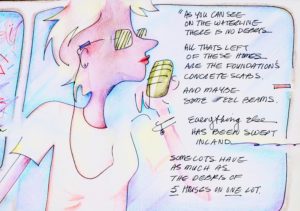

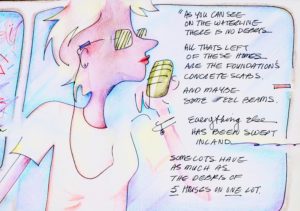

“Is this on? Okay. So can y’all hear me now? What you’re looking at here is the water line, which as you can see has no debris. All that’s left of all these houses here are their foundations’ concrete slabs maybe some steel beams like that one there. Everything else has been swept inland. When we go further inland you’ll see the debris of five houses on one lot. Now that house right there is one of the lucky ones still standing, but inside everything was completely destroyed by the storm surge water, driven by 150-mile-an-hour winds. That big old oak you see there? With the mattress stuck up between her top branches? She’s dead. The roots on all these big old trees drowned in salt water.”

Margaret may be the only person on the bus who is uncomfortable speaking into a microphone. The other seventeen people on board are performers — actors and singers who have volunteered to travel to the ravaged Gulf Coast to Christmas carol for disaster victims. Margaret is a Disaster Corps volunteer who has come to the coastal town of Waveland, Mississippi to help rebuild houses annihilated by Hurricane Katrina.

I’m the only one on the bus who did not watch the Katrina Smörgåsbord as it was being served up on television and spread over the web. Dissected in papers. August found me wrapping white gauze and string around eggs and bones affixed to canvas; exploring ideas about the sanctity of nature and the mystery of life, death, birth and regeneration in my art studio in the country. I heard a hurricane was expected to hit from my reliable old companion, a portable radio and cassette tape player faithfully tuned to the local classical station during a news break between Pictures at an Exhibition and The Planets.

We are all in flux; the moons of Jupiter, the rings of Saturn, the awkward dwarf with his irregular rhythms and forcible outbursts, the ballet of unhatched chicks in their shells, the castle, the catacombs, the cackling witch. Colossal sunflowers, their wide brown faces wreathed in yellow petals, show off against the postcard blue sky of September. They will die standing up, addressing October. Leaves the color of canaries first flutter then whirlpool with differently shaped red and orange cousins until they all succumb to gravity, forming fall’s familiar smell. The coverage of Katrina has also faded. She’s falling now, feeling forgotten and afraid of being dragged into dark beds of slippery memory. Then November moves a cloud. Helium titans float over, pull her up, and put her back on the radar.

Katrina is being celebrated in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade to the tune of “When the Saints Go Marching In.” A cabaret singer has rewritten the lyrics in Katrina’s honor. The camera man cuts to the crowd for close ups: a brown baby picking her nose, a round black man in a baseball cap nodding his salt and pepper head. The blue cohost in ear muffs is moved to a tear. Commercial break. Macys and Thanksgiving tolerate each other, but they are not close; one born of commercialism the other hailing from old puritan stock.

By the time the turkey, stuffing, mashed potatoes, gravy, creamed pearl onions, turnips with bacon, string beans with almonds, candied yams, plus pies: apple, pumpkin, and mincemeat were consumed, Thanksgiving had also stuffed my inbox to exploding—with renewed appeals for donations to help survivors of Hurricane Katrina. Every charity that couldn’t find me last summer was back: The American Red Cross, Salvation Army, Feed the Children. What to give? And to whom? International Association of Fire Chiefs? Coalition to Restore Local Louisiana? Days End Farm Horse Rescue? Charities infinitum were soliciting funds. I gravitated toward a nonprofit called World Art Project soliciting volunteers; actors, singers, storytellers, artists, to Lift the spirits of people without a home, or possibly a family this Christmas.

We will sing Christmas carols and tell Christmas stories. We will hand out gifts and supplies —”and spread sunshine all over the place, just put on a happy face” my earworm chimed in. Be ready to rough it in a no frills situation. Expect to sleep in tents and borrowed dwellings, maybe motor homes, the organizers warned. Steel yourself for the hardship of existence sans shower for a day or two. Sans shower? Who wrote this? I scroll and discover. The author is my friend Sara, World Art Project’s freshly minted “Musical Director” and, apparently, top recruiter. Many moons ago Sara and I were singing-waitresses at Once Upon a Stove. These days we run into each other at voice-over auditions. I give her a call. Sara’s voice is deeply sexy. “Does this mean you’re coming?” “I’m thinking about it.” “What’s stopping you?” she asks.

We meet at Alice’s Teacup. “I have my doubts.” I confess, sipping the jasmine Sara suggested. I remember the flavor now. It’s like drinking l’eau de toilette. I should have stuck with my old steady, Earl Grey. Sara is surveying raspberry preserves, homemade clotted cream and the variety of scones, tea cakes and Lilliputian sandwiches artfully displayed on a three tiered caddy taking up most of the table, its finial on par with the top of her head of Raphaelite curls. “Care for a pumpkin scone, Cupcake?” Did Sara always nickname people after baked goods? “Just don’t call me Brownie” I say meaningfully. Sara smiles in that I read Rumi way and adjusts the luminosity of her flawless complexion. Either she didn’t catch my drift, or she’s being Zen. “Brownie did a heck of a job!” I impersonate Dubya. “Don’t be political. Be merry. That’s the gig,” Sara says.”I don’t know,” I say “It all just seems so ‘Up With People‘”. “What are you afraid of?” I set down my vintage tea cup decorated with chirpy songbirds on its charmingly chipped saucer. A beheaded songbird is still flapping its dainty wings.

“I’m afraid” I say, “that if my house had been destroyed, or my grandmother’s heirloom collection of civil war clothespin dolls had vanished, or my cat drowned while we were stranded on a rooftop five days waiting for a helicopter to rescue us, and three months later FEMA still had not found me and my family a trailer to live in, and a bunch of New York actors suddenly showed up singing Rudolph the Red Nose Reindeer I might pull a Bushmaster semi-automatic rifle out from under my rain poncho and start shooting Dasher! Dancer! Prancer! Vixen! Comet! Cupid! Donner! Blitzen! and those city people who rode in on them! Sara laughs. “Your talents are a gift to be shared, my little cheesecake.”

“I love that you still think music can change the world.” “I’m not sure Rudolph qualifies as music, but it can’t hurt.” Sara with your teeth so bright, won’t you guide my sleigh tonight? My earworm is being funny. Note to self: buy bleach strips. “I don’t know. I hate show people showing people how much they care stuff.” I pop a sugared pecan in my mouth. “We’re showing the people in the gulf coast New York hasn’t forgotten them.” I envy Sara’s skin—sand colored and smooth as a bossa nova. She breaks off a piece of sea salt caramel brownie and holds it in front of my mouth. “Open.” I obey. “Is that not heaven?” I wash it down with a sip of toilet water.

When I get home there’s message on the machine: Hello, Cupcake. Liza is thrilled you’re on board. We’re putting you in charge of the Children’s Library visit—a day of storytelling and art projects with the kiddies. You’re perfect for it. Trust me, my sweet.

BIG BLUE

The alarm goes off more rudely than usual. How can anyone get up when it’s this dark except to go to the bathroom? It’s a December Saturday. Once outside, the hum of the city feels friendly, the crisp air and the half-asleep lavender-blue sky encouraging. Stephen opens the car door for me. My arms are loaded with an empire of glombo cookie concoctions he baked for the troops and packed to bulging in vast Tupperware tubs. The ride downtown is traffic free.”You brought your handkerchiefs?” he asks.”Yep.”Don’t forget—keep your pants tucked into your socks.””I will, but I don’t think that’s how black mold travels.””Did you pack the alcohol swabs?””You put them in the baggie with toothpaste and stuff, yes. Thank you, honey.” “I hope you took your happy pills.” “At least you won’t have to be around me if I didn’t.” “So who’s your roommate? Sara?” “I have a feeling it’s gonna be a whole bunch of us in one funky tent.”

Actors armored with steaming paper cups of coffee mill about the parking lot as if we’ve all been booked on a Law and Order shoot. I’m shocked by the immensity of a big blue, shiny new, practically-U2-rockstar-road-tour type bus idling in excess. Clearly it’s not part of our no frills package. Maybe a senior group is going on a day trip to Atlantic City. Where are the seniors? Big Blue’s overwhelming rumble sucks the oxygen out of coherent questioning.

“Hey, Beauty!” Liza throws her arms around me. “We are super-psyched you decided to join us!” Liza is so pretty. Ivory skin girl. Her brunette bob and wide set velvet brown eyes are familiar from the many print modeling and on-camera commercials she’s appeared in. I introduce Stephen. Liza mentions being in the process of giving up her acting career to focus on her baby, the World Art Project. “So what do you think of our bus?” she grins. “That’s ours?” I ask.”Can you believe it?” She glances toward a couple of actors loading cases of wine onto Big Blue and profusely thanks Stephen for the cookies.”I’ve got to get over there and be in charge!” she says. “Go, go!” we say. Liza prances off to talk to a guy in a pink Oxford shirt. “That must be her husband,” I say “What does he do?” Stephen asks.”I think he’s a Wall Street guy.” The bus starts making back-up beeps.

Heebie jeebies threaten to mug my bonhomie. What did I expect? A Freedom Rider’s Bus? The Partridge Family Bus? Something yellow? The wheels on the bus go round and round round and round, round and round, the wheels on the bus go round and round all through the town. My earworm is warming up for the field trip. Stephen kisses me good bye. “I’m proud of you,” he says. I sneeze. “I’m allergic to saying good bye.” I say.

“Deck the halls with bows of holly, fa la lala la la la la. Tis the season to be jolly, fa la la la la la la la la”. “Brighter! Sprightly, folks! Come on, give me some goddamn jolly!” Somewhere between the time when Big Blue emerged from the Holland Tunnel and pulled onto the Pulaski Skyway, Sara mysteriously transmogrified from mellow jazz singer/spiritual seeker into Commandant Krieger, the “practice makes perfect” taskmaster, musical director, and conductor of the Katrina Carolers. A grinding rehearsal schedule which no one dared complain about in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia because “We’re so lucky” compared to disaster victims, took its toll as we were leaving Tennessee.

A wave of group-doubt washes over us during the umpteenth run through of “Let It Snow”. “Once more from the top. Really think about what you’re singing this time, Dumplings!” Sara raises her arm and counts off with a delicate Gestapo hand. And a one, and a two and – we start singing: Oh, the weather outside is frightful, but the fire’s so “—Wait! We can’t do this!” shouts Ron, waving his sheet music in the air.

Ron is a comedian who used to be fat until he got his stomach stapled, llost sixty pounds, Now he’s stuck trying to convince people he’s still funny. “Problem, Crumb Bun?” Sara turns up the volume on her baby blue eyes. “The weather outside is frightful?” Ron exaggerates for full effect. “But the fire is so delightful,” Sara finishes the phrase, not sure what he’s up to. “He’s right!” says Sue. “It might not be the best lyric considering the kind of weather they’ve been through.”

A debate about whether frightful weather is an appropriate lyric to serenade hurricane survivors ensues. “It’s a snow storm,” I say. Liza sadly shakes her head. “That’s still a storm,” she says. Liza spent months volunteering at Ground Zero so we respect her grasp of disaster etiquette. Liza believes hearing “the weather outside is frightful” might traumatize some audience members. No more than our elf hats I think. “Better to err on the side of safety,” Sara says. “Okay folks, ‘Let It Snow’ is out. Let’s move on to “Silver Bells”. The joint sacrifice of a favorite number for the emotional safety of survivors pulls our group together. Although my own voice feels a bit scratchy from the re-filtered bus air, we blend in a way we hadn’t before on ‘Silver Bells'”,

City sidewalks, busy sidewalks, dressed in holiday style

In the air there’s a feeling of Christmas..

People laughing, people passing….“Whoa!” This time Sara stops the song.”You can’t mean ‘people passing,” I say. “Oh wow, I hadn’t even thought of that.” “We can’t say sidewalks” says Liza, with a knowing look to Sara.”They have no sidewalks anymore!” Ron chimes in. Nobody’s kidding. The ax is falling on “Silver Bells” when Derrick, our tallest and strongest singer, with roots in gospel—the sole African-American in the choir—jumps out of his seat and points out the window. “Look! This is where you start to see it!”

We watch horrified as tree after tree, broken and bent, flies past our eyes like toppled Goddesses torn limb to limb by the furies.”Ah choo!” The further south we’ve gone the more clogged my nose and ears have become. I hope this isn’t the flu. I can just hear my therapist. “It’s interesting that as you’re about to meet total strangers who will tell you their stories of grief, loss and death, your ears become clogged.” And what about my throat? Am I resisting singing “Here We Go A Wassailing” to trauma victims?

I signed on expecting to sleep in a damp tent surrounded by black mold and mosquitos. I ordered a sleeping bag, packed my big rubber boots, umbrella, insect repellent and long underwear, as well as a red scarf and hat as instructedthough it turns out Sue brought elf hats for everyone. When we arrived in Mississippi a motel with running water and electricity had miraculously become available at the last minute The proprietor is a gentle man who apologizes for the lack of services. He is still waiting for a trailer for his own family to occupy three months after the storm. His wife couldn’t bear the stress and returned to India. I picture India as a hotbed of chaos, a complex mix of grinding poverty and vibrant wealth. I hope it feels better there than here.

Liza and Sara insist it’s too dangerous to risk me infecting the troops with my now hacking cough and mucous expulsions so while other carolers double, triple and even quadruple up I get a room of my own. Oh rapture! Alone at last. My ecstasy endures for about three minutes before it morphs into heebie jeebies. It’s one thing to have a room of one’s own in a Virginia Woolf way, but this feels more like when a celebrity makes a show of helping humanity in a third world country while staying in a hotel with fresh towels and a mini fridge.Where do the motel owner’s kids sleep? Is Stephen still awake? He insisted on buying me a cheap cellphone for this trip. I hate cellphones. My head is too stuffed to try and figure out how to use it.

Liza has arranged for a Disaster Corp volunteer named Margaret to take us on a guided tour through what remains of the city of Waveland tomorrow.I find the Nyquil Stephen packed and throw back a capful as the sound of fellow carolers guzzling cases of wine comes through the walls. Reliably tempered to midnight green, the soothing syrup regulates a mood-tide littered with the day’s flotsam and jetsam. So much nonsense washes up on the shore of a subconscious dreamily determined to process it all in a parallel world. I gingerly side-step New York City potholes sunk in Mississippi sand dunes to cross a moat over a treacherous lagoon. Up ahead the Taj Mahal is about to be demolished by a gigantic jingle-bell wrecking-ball. My own snoring wakes me up just in time to see the sunrise out the window of my room.

WAVELAND

Watching the devastation from behind Big Blue’s large tinted windows is eerie, like being on a tour of Hollywood Star’s homes only Katrina is the star—and there are no homes. We don’t see people either. We hear voices spray painted on makeshift signs, nailed into unbalanced telephone poles. Voices splattered across bent aluminum siding and cracked clapboard: “Betsy, I took some things. Call me!” is scrawled in orange over what’s left of a once white garage wall, followed by a phone number; a splintered sheet of plywood tacked to a battered oak, begs “Please save tree planted by grandson”; a slice of cardboard propped up against a tangled metal folding chair sitting on a lone slab of concrete reads “Katrina took my house. State Farm took the rest.” Many signs say “Don’t Doze.” Fall asleep? Somebody says “bulldoze.” Oh. Right.

Every house is marked with an X, applied in red or yellow. Red means tear this house down. Yellow indicates the structure remains somewhat sound and might be salvageable. The X is followed by a numeral denoting how many bodies were found inside. I get a good photo of an X followed by an 0 and then I get heebie-jeebies. But it’s not the idea of dead bodies creeping me out, it’s me — snapping pictures like the tourists I wanted to kill for doing the same thing at Ground Zero.

A house cat behind a window looking at birds is still hunting. She knows she’s a hunter. But what are we humans behind our car windows, phone and computer screens. Disaster voyeurs? First responders? Audience? Participant? Behind a glass window I can be whoever or whatever I choose to believe I am. That’s my occupation. Have you had a good life? Are you proud of what you’ve done?

The World Wrestling Federation hires me to be evil and scary. I stand in a studio behind a glass window wearing headphones and deliver my lines into the microphone hanging over a music stand, alternately reading from the script and looking up at the visuals on a screen. A haunted Victorian mansion is on fire. Backlit ghost children float-walk through the blaze in the nursery, float-walk out flame-licked windows, and float-walk into the dark night, eerily intoningRing-a-round the rosie, a pocket full of posies, ashes, ashes, we all fall—

THUDUMPhhh! Ouch, my eardrums. The metal thud with reverb sound effect—or as it strikes me, “the omnipresent bang-the-viewer-over-the-head-with-a-cyclopean-frying pan-deployed-by-testosterone-addled-film-editors-to-telegraph-gratuitious violence effect” punctuates the cut-away.

Two bulky bare-chested wrestlers with bloody faces are bashing each others’ brains out. I pride myself on my ability to take direction well. Shave half a second? Sure. Pick up the pace when Mysterio rips off his mask and stomps on Cena’s face? Okay. Sound sexier when the blood squirts out of his nostrils? No problem.

Over the air waves and through the tube and into your brain I come. One day I’m the voice of a wicked witch pitching a wrestling match. Next day I’m a Judy Dench-like dinosaur on a kiddy cartoon. I’m game to play ball with pretty much any identity; perky mom, rye mom, hip grandma, relieved arthritis sufferer, wacky yoga instructor, chipper bank teller. A great thing about doing voice-overs is that it doesn’t matter what I look like. I could be naked behind that microphone. Sometimes I actually feel naked, especially on those occasions when it’s my job to tell the whole truth:

You should not take this medication if you have certain types of stomach problems, glaucoma, or have trouble emptying your bladder. The most common side effects are dry mouth, constipation, indigestion, and abdominal pain. Please read the Patient Product Information Pamphlet.

That disclaimer is what’s called “Fair Balance.” Pharmaceutical companies aren’t allowed to advertise what a drug can do for you without also mentioning what it can do to you.The notion that balance exists on the air, or that somewhere things actually are fair comforts me—in theory. In real life balance often eludes me. I teeter on a tightrope, umbrella flailing, negotiating the gray matter between making a living and the art of living. Being alone with the sound of my voice in a dimly booth is a harmonious experience, equally powerful and seductive

Now, for the first time ever, get a behind the camera, beneath the glamour look at Sports Illustrated, the Making of the Swimsuit Issue; the poses, the suits, and the all– important cover shot. Sports Illustrated, the Making of the Swimsuit Issue.

I enjoy the intimacy that connects and yet separates me from the faceless audience I’ve been hired to impact (upon), but once outside the recording booth, pounding the pavement in the light of day, I’m struck by the notion that promoting Sports Illustrated’s, Making of the Swimsuit Issue, or the World Wrestling Federation broadcast of the Great American Bash, or romancing the microphone for the purpose of selling mouthwash, is not all that helpful to humanity. I feel a bit more noble when I’m doing a public service announcement: “Protect kids from cancer before the opportunity goes up in smoke.This message is brought to you by the American Cancer Society.” Still, I’m not exactly putting myself on the line like say Médecins Sans Frontièrs. Is singing carols to Katrina people more fruitful than saying “Don’t smoke” to cancer people?

“Helloo, Waveland, Mississippi!” We are about to sing for our first audience at Project I Care Village, a huge white feeding tent right next to the ocean. Liza is beaming. “It’s so great to be here in Waveland! We just got off a bus from New York City and we’re here to spread some Christmas cheer! Because in our time of need you folks were there for us!” Liza tears up as she speaks. That happens a lot on this trip. The feeding tent is bare bones. Wood chips form the floor. There are three very long rows of tables with folding chairs, a makeshift trailer kitchen, a serving line with hot boxes, and piles of donated supplies including Dora the Explorer napkins, plastic forks and spoons stacked in every corner. Among volunteers gathered for a free meal are a church group from Tennessee, a Jewish group from Minnesota, a Virginia family home schooling their kids, and a whale-shaped local who breaks into an Elvis impression if you make eye contact with him.

The folks in the feeding tent don’t know quite what to make of the seventeen actors from New York clad in kooky hats and brightly colored scarves. There are more carolers than audience. No matter! We erupt into “Deck the Halls” and fill the tent with fa la la la! “All join in!” Liza cheers. “Folks drove up from Mississippi and Louisiana and cooked jambalaya out of the back of their trucks to feed our fireman!” But Liza’s plea plops like a pebble into a pond of blank faces while visions of mortifying performances from my past dance in my head—ie: doing my Katherine Hepburn impression on open mic night in what turned out to be a Sports Bar in Astoria, Queens.

The folks in the feeding tent aren’t smiling. So Sue, our peppiest caroler, in a red felt Santa hat with a jingle-bell hops elf-like into the audience, grabs a five-year-old named Natalie and pulls her up to sing along. Natalie has obviously been watching “American Idol”. She moves like a professional contestant. People start to grin. It’s time for our big finish, “The Twelve Days of Christmas”. Liza insists we do with the cheesy hand motions she taught us–to my horror: Twelve drummers drumming, we hold up ten fingers plus two, then pretend we’re drumming. Eleven pipers piping, we hold up ten fingers plus one, then pantomime playing piccolos. Ten lords a-leaping hands up over our heads with fingers spread out as we jump in the air! Nine ladies dancing, we do the can-can; Eight maids a-milking, hold up eight digits then pull on imaginary utters; Seven swans a-swimming, five fingers up on one hand, two on the other, then stretch out our necks; Six geese a-laying—I cannot go there.

Five golden rings is that big hold the note as long as you can moment. The suspense mounts. Just how long can those New Yorkers in red scarves and elf hats actually hold that darn note? Longer than people with higher self-esteem would but we’re actors so we can’t help it. Then it happens. The audience breaks into applause. All nine of them join in singing. Now we bring it home—Four calling birds, Three French hens, Two turtle doves, And—we slow to mime utter exhaustion, Ron goes so far as to pantomime almost fainting—a partridge in a pear tree! The audience is up on their feet. Sara catches my eye and winks.

THE LIBRARY

“Can we go in the house? Can we?” Two little boys grab my wrist and pull like obdurate mongrels at the end of a rope. Their eyes are on a powder blue playhouse with cream colored trim and a nifty front porch situated in the Children’s Section of the Kiln Library, where fifty-nine six year olds have congregated to hear us act out old fashioned Christmas stories I’ve curated from the internet, rewritten into radio-like scripts, and cast with the carolers. The librarian tells us the roof and windows of the Kiln Library here in Mississippi were damaged but they’re lucky. Neighboring libraries in Bay St. Louis and Waveland weren’t so lucky. Pearlington Library lost everything and the library in Pass Christian—like the town itself—was wiped off the map.

The staff settles the children on the floor. We set ourselves up to perform in front of the playhouse porch. Ebony and Ivory live together in perfect harmony, side by side on my piano keyboard, oh lord why don’t we?—Out, damn’d Earworm! out, I say! but I do so much wonder how come we don’t see any black kids in the audience. Jumpy girl in the pink and orange striped turtle neck looks “mixed race”—African American and American Indian? and plump shy guy who won’t take off his too small lime green ski jacket has an Asian thing goin on, but this crowd is pretty much white tykes.

“Chickadee-dee-dee-dee! Chickadee-dee-dee-dee! Chicka”

“Cheerup, cheerup, chee-chee! Cheerup, cheerup, chee-chee!”

“Ter-ra-lee, ter-ra-lee, ter-ra-lee!”

Cast as woodpeckers, snow buntings and chickadees, the carolers gleefully inhabit their avian roles — chirping and trilling, twittering and warbling, and spreading their thespian wings in the Katrina Carolers’ staged reading of “The Birds’ Christmas,” a story “founded on fact” by one F.E. Mann (1852-1910). The noted fact tells us that once upon a winter in the thick pinewoods of Northhampton, Massachusetts, robins and other migratory birds warmed a solitary Thistle who decided not to fly south with his family.

Derrick is a hit in the role of Thistle Goldfinch’s savior, Mrs. Chickadee, tweet-tweet-entreating her fellow birds to group-hug poor freezing Thistle Goldfinch as he realizes that staying north might not have been such a good idea after all, but the kindly winter birds pitch in and help Thistle find seeds and point out a cozy evergreen nook to sleep in. We learn to live when we learn to give each other what we need to survive, together alive. Is it wrong to hope a robin will eat my earworm before its next refrain of “Ebony and Ivory”?

We are all made of water and songs and stories. Once I caught a sparrow with my hands, its quick, tiny heart beating in my palm.” Another time I found a baby blue jay on the ground. I fixed him a recovery room in the bottom half of a cardboard gift-box, fed the fallen fellow water from an eye dropper and prayed he would get better. I pictured myself teaching him how to fly and imagined he’d come back and call to me from a branch in a tree. The next morning I woke up at dawn and ran down to check on him and he was dead, so I went back to bed and pretended I didn’t know that yet.

“The Bird’s Christmas Story” ends happily as we prompt our dividedly rapt and antsy spectators to stand up and fly—flap and flutter! Sara endows Downy Woodpecker with percussive depth and Sue’s Papa Goldfinch sounds like a valley girl. Our next story, “The Doll’s Christmas Party” by Viola Roseborough (1857-1945) features Victorian dolls in a medley of sizes, shapes and characters. I’m the narrator.

It was the week before Christmas and the dolls in the toyshop played together all night. The biggest one was from Paris. One night she said, “We ought to have a party before Santa Claus carries us away to the little girls. I can dance, and I will show you how. I can dance myself if you will pull the string,” said a Jim Crow doll.

I was relieved no one on the big blue bus had said “White Christmas” sounded racist but “Jim Crow Doll” gives me the heebies. I change him into a Clown Doll assuming the author was racist. In fact, she was an abolitionist. Are we all racist on some level? Like if I’m describing someone (not white like me) I used to automatically say this black lady or that Chinese guy. Last week I heard a scientist on the radio say babies do not discriminate against each other based on skin color—they just notice it.

Before I came down south I’d never even heard of most of the cities on our itinerary—except New Orleans, but the flood of horrific images beamed from the savaged bowels of the Lower Ninth Ward was so stuck in my brain I just assumed our audiences would be poor and black. In fact, like most towns on our itinerary, Kiln had a middle-class white population. The population in our story is “mixed-doll”—an inclusive celebration of diversity in age, race, toy species, and ethnicity featuring a French lady doll from Paris, a big rag doll, an old Mother Hubbard doll, baby dolls, a Jack in the Box, a toy monkey and an Irish doll who objects to the menu.

Patsy McQuirk said he could not eat candy. He wanted to know what kind of a supper it was without any potatoes. He got very angry, put his hands into his pockets, and smoked his pipe. It was very uncivil for him to do so in company.

Once upon a time noble ladies wore “tiaras” of potato blossoms in their hair. My Irish-American mother refers to the potato famine of the mid nineteenth century as if it happened yesterday. Doug, a cute looking musician with a James Taylor vibe, brings a lyrical lilt to Patsy’s Irish brogue. “That’s Lucky!” A freckle face pixie in pigtails jumps up and down in her light-up sneakers—blink-blink-blink! “They’re always after me Lucky Charms!” ad libs Doug, turning Patsy McQuirk into Lucky the Leprechaun. White Fluffy Frosted Lucky Charms, They’re magically delicious! Lucky Charms give me heebie jeebies. Remind me of nibs of colored chalk on the ledge of a blackboard. Kids love the miniature marshmallows shaped like hearts, shooting stars, blue moons (They’re called “marbits.”) I’ve done my share of cereal commercials addicting kids to sugar. I’m evil.

Story time is over. Now it’s time to sing. We kick off with “Jingle Bells”. Oh what a fun it is to serenade fifty-nine six-year-old faces full of wonder. A skinny little boy with very big eye glasses raises his hand after “Jingle Bells”. “That’s the best song I ever heard in my life!” My kind of critic. He says the exact same thing after “Rudolph” and “Frosty”. Some people know how to live in the moment. We finish the show with “The Night Before Christmas” and a big surprise, “Ho ho ho!” Our own jolly Ron has donned the red Santa suit and white beard, and is loaning his lap for the occasion. He looks like he’s gained back ten pounds in the past two days. Stephen’s cookies. Wee wenches and weeny lads line up to ask for 4 x 4s and Barbies, but one moppet is too afraid to ask for anything because “It will disappear.” “All these kids have lost their homes,” the librarian tells me. No wonder those two little boys were desperate to go inside the playhouse.

Our last half hour at the library is devoted to art-making. Derrick helps me unfurl a giant roll of not quite white—somewhat lavender tinted—colored paper across the floor which will become a mural by everybody. I’ve heard that lavender is a “healing” color. I bought the roll at the Dollar Store a year ago assuming the noncommittal shade was the manufacturer’s blunder that made it so cheap. We pass out colored markers, crayons and stickers of happy faces, footballs and flowers—silly sayings, stars and exclamation points.

Derrick and I lie on our stomachs with the kids. They’re drawing dinosaurs, the sun, houses and trees—cats, clouds and families. They map out rainbows, color designs into butterfly wings and sign their names. A bony boy with a chipped tooth clutches a marker in his fist and scribbles out the letters of his name in its mirror image. “Is that a trick?” I ask. “That’s how he writes everything” his sister tells me. The librarian gives me a hug and says “Maybe I’ll go home and put up a tree after all.”

JOY

When peace, like a river, attendeth my way, When sorrows like sea billows roll; Whatever my lot, Thou has taught me to say,It is well, it is well, with my soul. The Coastal Chorale is singing at Saint Augustine Church in Bay St. Louis. I’m sobbing in my pew. The deep pink cowboy-kerchief I thought I had in my pocket has gone missing. My sleeve is officially soggy. Meanwhile, Joy’s cuffs are immaculate, her wrist and hand gestures, meticulous. Joy stands tall in a regal red blazer and bright white turtle neck, conducting the choir on the altar. Her silver cropped head holds sway over a sea of feather-cuts and soft coiffures; a page boy here, a comb over there, manicured beards, clean shaven cheeks and pretty lipsticks.

We’re honored to have been invited to sing in communion with the Coastal Chorale in the first half of their annual Christmas Concert which our intrepid hosts refused to cancel. They are elegantly turned-out from head to toe. How do these people manage to look as if they still have closets and dry cleaners and laundry rooms while our kooky hats and scarves have taken on a weariness that’s beginning to make us resemble a homeless people’s chorus? Joy invites us to visit her at home the next day.

“My son and I watched from the third floor of our house as the neighbors’ furniture floated in our front door and out the back door.” Joy says she felt blessed when a couple of bottles of Scotch happened to float by, giving them something to wash their hands with while they waited three days for the water to subside. I would’ve drunk it. Joy and her partner RJ had just completed an extensive and expensive renovation of their house when Katrina invited herself for tea and in addition to the usual menu of destruction turned Joy’s priceless collection of rare sheet music into limp layers of phyllo dough.

A collectable Depression era doll with dimples—Shirley Temple, wears a once mint-green taffeta party dress, her curly head of perfect blonde ringlets is caked with mud. She lies near a box of oil pastels and two microphones. I take her picture.

Spread on the ground outside Joy’s battered studio is what’s left of her work as a potter. Miraculously, nearly every one of her creations has survived intact. Clay pots, glazed pitchers, and colorful bowls sit tilted and tipped like picnickers on a blanket. A textured sand bowl with a musically jagged edge and glazed jade interior—beckons. It’s engraved in patterns of eclectic symbols; a flock of apostrophes, a clique of concentric circles, a crucifix, and in a rectangular stamp—a relief reminiscent of The Scream by Munch meets the Home Alone poster, a girl holds her face like Macaulay Culkin —the words “Oh no!” imprinted over her head.

The bowl resonates like an ancient relic of the hurricane to come. I want it so much I know I won’t be allowed to have it. “Is this for sale?” I ask. “Y’all can have that one.” Joy says. “No. Really?” “It’s wonderfully eccentric.” I say slowly turning the bowl. It revels in aspects of Joy her other pots don’t expose. “I want to buy it.” I insist. Joy raises her eyes to heaven like a jaded angel reporting another human foible. “How much?—Really, please.” “Forty?” she succumbs magnanimously. Oh blessed fluky art-find. I reach into my pocket as if it’s as deep as Brad Pitt’s. Like I’m doing my part to bring back the Bayou. Oh no! . I’m on stage with no pants on. “I left my wallet back at the motel,” I confess. Joy breaks into a lopsided grin. “You were meant to have it.” Joy still believes things happen for a reason. I trudge through the thickening sludge, carefully stepping up into Big Blue with Joy’s bowl pressed to my chest. I set us into the milky glow of a window seat’s northern light.

SONIC

Stop the bus!” Liza squeals like a kid in a car seat who’s spotted a Ferris-wheel. In cahoots with Cedric the bus driver, our fearless leader has been commandeering guerilla caroling attacks. No strip mall, gas station or fast-food restaurant is safe from our drive-by sing-a-longs; Popeye’s, Wendy’s, Arby’s and now—Sonic Burger, where roller-skating waiters and unsuspecting customers can’t help notice a big blue, shiny new, practically-U2-rockstar-road-tour type with New York plates, pull up and spill out adults in Santa Claus hats who hit the black top singing.

These “stop drop and roll” (Derrick’s description) excursions make me want to hide in the back of the bus or play the flu card. I force myself to push the bus door panel outwards from its plug socket and step down into the parking lot, standing as far back as I can from our peppiest crusaders— who are cheerfully bullying customers ordering Corn Dogs and Cream Slush Treats to sing along with “The Twelve Days of Christmas.” I switch into autopilot. Coming up on “six geese a laying,” the sight of a clump of teenagers abusing straws at the condiments counter ignites a flashback. I’m doing stand-up in a dimly lit, mold infested comedy club called Dangerfield’s on what turns out to be a prom night for bridge and tunnel youth. I’m doomed to follow a comic who introduces himself as the Greek God, “Feces,” whips out a pair of balloons, rips into sight gags about his grandmother’s sagging boobs, and kills with a football routine depicting a limp wristed screaming queen who plays “tight end” topped by a brain damaged black quarterback spewing malapropisms that has the audience screaming. I was counting on doing my singing impressions of rock stars but the sound system won’t play my music tapes. I’m being heckled by a herd of rented tuxedos and wilted wrist corsages and gassed with alcohol-breath fumes when suddenly—

Applause breaks out! Sonic roller-skating waiters, cooks and customers are clapping and laughing. I am not bombing. Pumped by audience response we mingle with locals, chow down Chili Cheese Tots and suck up Java Chillers and Blue Coconut Slush. Derrick joins a couple in their fifties sitting with a little girl and chats over the table. Turns out they disowned their daughter for marrying a black guy and their daughter and her husband have been missing since the hurricane. The mixed-race kid is their grandchild Cedric starts the engine and honks the horn.

We’re piling back onto the big blue, shiny new practically U2 rock star road tour type bus, still pumped and smiling about the generous reception of our performance when a Goth teenager pulsing with pimples emboldened by his long black raincoat shouts after us— “Yea, that’s right! Y’all go back to your nice homes in New York!”

ROOMMATES

“He nailed us!” I moan. “Stick these under your tongue Dumpling Breath.” Sara has emerged from the steamy bathroom, head turbaned in a white towel, face freshly cleansed, toned, moisturized and tingling from an all natural skin-care product regimen, to deliver a homeopathic remedy into my chapped hands. “I can’t get Goth Teen out of my head.” I say. “You’re supposed to take this at the first sign of cold symptoms but better late than never, Cupcake!” She drops the tablets into my palm. Liza’s ringtone goes off. Sara and Liza and their cellphones are my roommates now. They are unafraid of contamination.

Neither Sara nor Liza heard Goth Teen call us out, though their devices may have. “He practically spit!” I lisp, keeping my tongue down to dissolve the pills. “One kid, out of how many people has a problem with us?” Liza says giving me a “really now” look while dialing her mobile. Sara plumps up the pillows on the double-bed beside mine and plops herself down to get cozy with her cell and laptop. Liza is pacing and chatting into a wire. The image of an old telephone receiver I saw embedded in the sand at Waveland floats in the back of my head.

“It’s like he knows I order eight hundred thread-count Egyptian cotton sheets from the LL Bean Home catalogue and I eat sushi and I listen to NPR.” I say.”Guillotine!” Liza laughs. She’s multi-tasking: cell-phoning, wine sipping and alternate-listening to the conversation in our room, plus to who knows who or what in her ear buds. “Good taste is not a crime, Beauty.” she tries to reassure me—”Hey! Hi…” then directs her attention to an entity on the other end. “Trust me my dumpling,” says Sara. “Goth Teen is safe at home blowing up buildings on a video-game and feeling no pain in his heavy-metal lair.” Sara adjusts her snazzy little reading glasses to focus on her email. My own neglected cellphone broods dejectedly on the night table. I force myself to pick it up and notice Stephen has called three times. I haul the demanding doohickey into the bathroom to figure out how the hell to call Stephen back even though I’ve been shown—several times—by several people, including Stephen, Sara and Liza how easy it is.

Okay, I do know how to dial. Beep (beep beep beep) Beep beep beep—Beep beep beep beep. Nothing. Nothing is happening. Why isn’t this calling? I redial and keep redialing until I remember—you have to hit send! Ring ring ring. Amazing. “Janey! Are you okay? I left three messages. “I’m sorry. I forgot how to work this friggin cellphone.” “Hit send! He says. “I know. I’m sorry. It’s too hideous.” “I was worried. You have to check in. Are you okay? You sound sick.” “I’ve got some ear and throat thing. It sounds worse at night.” “Did you take Nyquil?” “Sara gave me something.” “Are you alright?” “No” I confess. “Something horrible happened.” “What? What happened? “I —feel terrible.” I sniffle. “Why? Janey, tell me.” “This teenager at Sonic (sniff) said we should all go back to our nice homes!” “Oh.” Stephen is relieved.

“He nailed us! We’re these privileged New Yorkers putting on a show. I knew this would happen. I knew it! And don’t tell me ‘Ignore it’.” “He’s right.” Stephen said. “He still has to stay there and deal with the difficult stuff he’s going to have to deal after you all go home, but that doesn’t mean we don’t do the little bit we can to help.” I see why Stephen is a shrink. “Besides, you don’t know what his house is like. His room might be bigger than Sara’s apartment. None of us know what another person’s life is really like.” “You’re right” I sort of admit.

“He’d shit his pants if he knew he was dissin ‘Max Payne’s evil nemesis—The Ice Cream Lady! “That’s ‘Grand Theft Auto'” I correct him. “And stop trying to cheer me up!” I say, grateful I know he won’t. “Heh, you can be Max Payne’s new nemesis—’The New York Christmas Carol Lady’!” Stephen ia doing a bad voice over announcer imitation, while noisily chewing his dinner in my ear. “What’s that line?”—chomp chomp—”that she says”–slurp—”before she commands her sidekick to off him?” “It will be a cold day in Hell before I let a Narc Cop stop me!” I grow.” After I hang up, I splash water on my face, and emerge from the bathroom and sidle up to Sara who is intimately interacting with her laptop. “Feeling better, Cheesecake?” she purrs. “Much.” I sigh.

HOPE

So far I’ve been in a coffin once in my life. In seventh grade I played Mrs. Sowerberry—the undertaker’s wife, in Oliver! Mr. Sowerberry shoved me into a coffin and slammed the lid. It wasn’t an ideal marriage. We caroled for the local morticians. Only four morticians showed up: one with his mother, wife and three children. Sue, in her elf wisdom pulls the kids up to join the chorus. Ellen, the mom reminds me of me when I played perky moms in on-camera television commercials. She has dark short hair and brown eyes and makes that “knowing Mom” face I used to sell breakfast cereals, laundry detergent and dog medicine.

Ellen’s husband Wayne is a funeral director and embalmer with the handsome look of a high school football player stuffed into a jacket and tie that’s too snug. When Wayne graduated in 1993, at the age of 22, he was the youngest person in the state of Louisiana to hold both a funeral director’s license and an embalming license. Nothing prepared Wayne for this hurricane. The first weeks after the storm were especially difficult. Between recovery and burials, Wayne personally dealt with over 200 bodies. He held services for about 40 of those. Ellen said Wayne bought clothing for some “pauper” cases, so they wouldn’t be buried wrapped in a sheet. Normally Wayne leaves his work at the door but Ellen knew he had to deal with a child when he came home very quiet.

I picture the little girl with black almond eyes who was singing and clapping and swaying with her church choir at the “Christmas Under the Stars” celebration, where we performed in Olde Towne, Slidell. “Her hair is straightened by a straightening comb heated in fire.” Derrick told me. “Thank you Vidal, but how do you know it’s not a relaxer?” I asked. “The hair close to the scalp. The ends aren’t as straight as the rest. She has the eyes of Lazarus,” he added. That night Derrick wrote about her on Liza’s blog:

Eyes that register being left alone in a dark and scary place. Her town was flooded and destroyed… For seven days the little girl with Lazarus’ eyes holed up in a town while water lapped and splashed. For seven days and nights… written of as casualties of the storm like others in her community.

It so happened a local TV News Reporter who couldn’t find anything about his hometown—which was the hometown of the girl with Lazarus eyes, was determined to investigate, so armed with a camera crew and rescue workers he finally found a way in and rescued the girl and her family. Ellen said before Katrina, “Camille was the guidepost.” Ellen was a baby when Hurricane Camille hit, but she grew up hearing the stories about Camille’s 20-foot tidal waves and 200 mph winds. “Because you hear the same stories every year at hurricane time, they become just that—stories.” Ellen told me. She said she never didn’t expected to end up with a hurricane story of her own, but she emailed this one to all of us.

When I came home the first time and saw the destruction around me I felt as though the end of the world had come. When my husband got to work helping with the recovery efforts and called me every night just to cry I lost hope. When my children helped me throw out all of their toys, books, and prized possessions, I lost hope. When my seventy year old neighbors had their home demolished I lost hope. When I got a seven thousand dollar check from the insurance company to repair forty thousand dollar worth of damage I lost hope. But my hope has been restored. A phone call about a special show, a big blue bus, a group of smiling faces, a wink through falling tears and a moment of joy for my children. These things have given me the hope I need to continue surviving.

LAND LINE

“Hi Jane, it’s mom. I haven’t heard from you since you got back and I wanted to know how the trip went.” My mother never calls—except to tell me someone has died or been diagnosed with a deadly disease. I call her when something good happens in my career—or somebody’s died or been diagnosed with a deadly disease. I pick up the phone.

“Hi Mom.”

“You sound down.”

“I’ve had the flu.”

“You sound down.”

“I’m still cloggy.”

“But you sound down.”

You can’t fool my mother. Especially when you’re not trying to. “I don’t know how people keep going.” I say. “But we all do.” she says.“But the people we met have lost so much.”

“All the back and forth to the hospital with your poor father before he died. People say ‘Mary, how did you do it?’ I never thought about it.”

“You can’t imagine the extent of the damage.”

“Oh, I can. I saw it on TV—I’m not a television watcher. Some of those widows— the gang at the coffee shop after church—go home and watch the damn television set all day long!”

“Mom, imagine if all of Rockville Centre—all the old trees, every school, church, temple, the library, stores—everything was gone or ruined—Plus Baldwin, Freeport, Oceanside——imagine if not just us, but all the neighbors; the Jolicoeurs, the Bonardi’s, Mrs. Sullivan, Mr. Ciskanic— “Him I could do without.”

“And on top of it, this God damn moron liar President still hasn’t—

“I’m not listening to that,” she interrupts. I stop talking. Let the dead air be.

A long time passes. A quarter second. Another half second. A whole second passes in silence. “I just wanted to know how your trip went.” my mother finally says.

“Thanks, Mom. I’m glad you called.” “Oh! I almost forgot! Jean Sullivan said she saw you on the news! A group of New York actors down south singing Christmas Carols for Katrina survivors. I said ‘Yes, that’s Jane!’ Jean was thrilled. You’re famous. You didn’t tell me.”

“It was a local affiliate. I didn’t realize they’d show it in New York.”

“I wish I’d known.”

“You never know what’s gonna end up on the cutting room floor.” I say.

“Oh I know. Your poor father—the time you girls were supposed to be on ABC. He called everybody and told them to watch. Then you weren’t on! Well, the phone started ringing.”

“Yes well it started out as human-interest story—sisters trying to make it big in the city. It was a news magazine format.” I explain. “I pushed to make it more of an entertainment piece. In the end the executive-producer killed it.”

“Dad was beside himself—You’d think somebody had died.” “We had a gig in Baltimore. We drove down in the banana boat. That’s what we called Dad’s yellow Cadillac—traumatized by dashed hopes.” “I don’t think you’re kidding.” my mother says. “Us not getting on TV was a major tragedy then.” “Well, I’m glad you’re back and it all went well.” my mother says. “Thanks, Mom. Thanks for calling.” I hang up.

I call Sarah. “Well hello, Cheesecake.” she coos. “How’s my little dumpling? “Sad.” I say. “We helped.” Sara says. “In a way.” I say. “Write about it. ” I hang up the phone. I’m home. I pull out a blank journal grab my Pilot Fine Point. Reach for a colored pencil. Pale yellow, perfect. Margaret’s hair, the microphone.