CHICAGO was created by Bob Fosse, and the songs were by John Kander and Fred Ebb. It had a successful run, was overshadowed by A Chorus Line, and was about 20 years old when it was revived as part of “Encores” at City Center.

“Encores” was then a new series of book-in-hand musical concerts with full orchestra, minimal scenery, costumes, and lighting. The original orchestrations were always a thrill to hear with the full sound as intended before time and economics had reduced them. The series was wildly successful, starting with Fiorello! in honor of the mayor who made City Center a civic auditorium. The stage usually held dance performances, and otherwise was dark for a large portion of the year. “Encores” was meant to fill some of that gap. It succeeded mightily, so much so that one City Center officer complained that too many people were coming to “Encores” concerts and that it was a “pain in the ass.” Later in the series—I designed 22 seasons which totaled 69 productions—people were putting their seat location subscriptions in their wills! And “Encores” was making too much box-office income proportionally for a not-for-profit. (Oddly, a problem.)

My first, and largest contribution to the series design was a gold-leafed proscenium frame to cut the City Center opening down to classic American musical comedy proportions—by mid-twentieth century tradition—18′ x 36.’ It was to be a signature for the entire series, however long the series was to last. I have a golden piece of the frame on my desk right now, as it has become the unmistakeable signature for CHICAGO as well.

Enlarge

The “Encores” proscenium always stayed, but as ever with success in New York, “Encores” grew and changed as the theater community eyed its great success. Increased attention meant increased effort, more costumes, more lighting, more of everything. Except no increased budget. I often joked that as resident designer I was the one assigned by the producers to say “No” and dash the dreams of the world’s most famous directors and choreographers.

And then CHICAGO changed everything … except the budget.

Enlarge

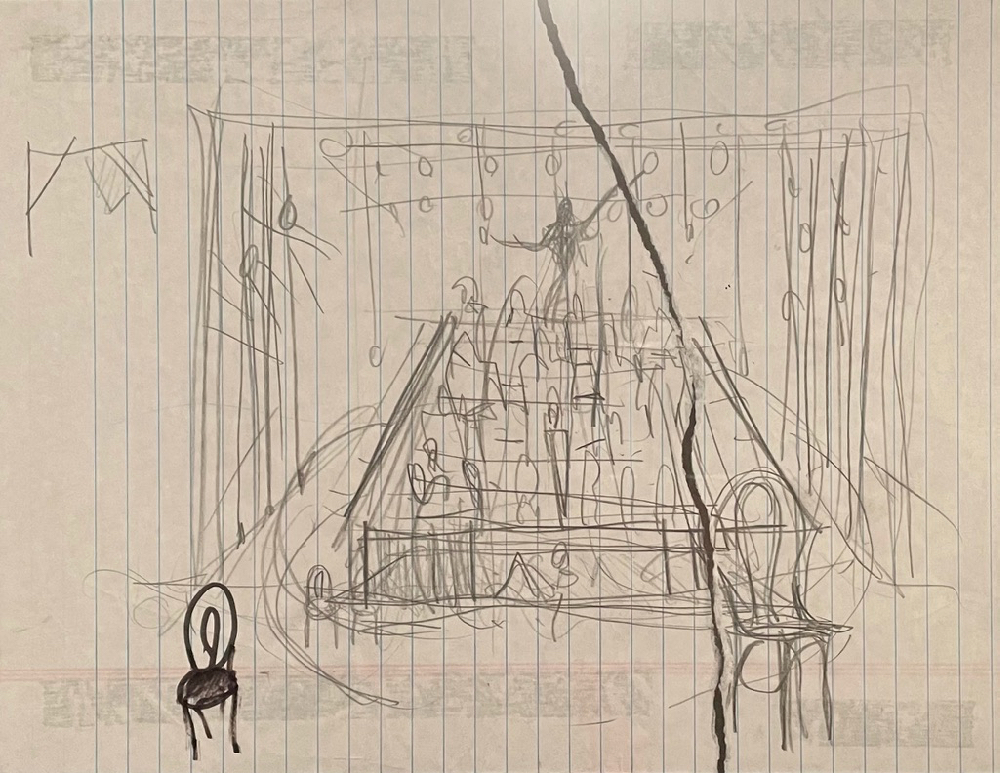

Original sketch by John Lee Beatty

Since there was a smaller jazz-type vaudeville band onstage (only one violin!) there was more stage space available than usual—especially to the sides of the smaller bandstand. And since it was a Fosse musical, there had to be dance. The stage always had five or six microphone stands across the front. The “Encores” orchestra was always sitting onstage after one disastrous exception of playing in the pit. There was a limited amount of dancing space left over. The Fosse dancing being ‘minimal,’ as opposed to wide-spaced ballet, was perfect for it.

Walter Bobbie, Artistic Director, was directing. As a director he was motivated , friendly, observant, but not yet terribly experienced. He was known to me as an actor. Blessedly, he did ‘get it’ as some others didn’t. He had a vision. He understood the great impact of the minimal without making an “Encores” show seem cut-down or cheap. He believed CHICAGO would work. It had a presentational quality that made it okay and more to acknowledge the concert style … and the audience.

Some twenty years earlier I had seen the original CHICAGO. I remembered especially Chita Rivera’s entrance through the floor, but knew no matter what they had done (Tony Walton was the original designer) we didn’t have the wherewithal to even suggest the rest of the original scenery. And Walter had, with the help of Tommy Thompson, cut most of the book, as we always did at “Encores.” None of the music, but the book. Which meant nobody sat down to play cards, or any of that original stage business. We wouldn’t have had the money for the prisoners to carry their own special illuminated jail bars, which was liberating. Economy of book and budget meant the show could move swiftly, the limitations worked to our favor.

We couldn’t, or wouldn’t, even make it look like the twenties. Which became a great blessing, as this was a revival of a seventies musical about the twenties which we were presenting in the style of the nineties. Now that our revival has lasted 25 years, there is yet another layer of ‘now.’ We decided originally not making references to the twenties was key. Even the prison lights were not ‘period.’

“Encores” productions were fast and totally underrehearsed. There were no previews for second-guessing. Designing went on a fast schedule in the early years, but Walter and I went at it intently, with enormous concentration. All of CHICAGO was put together fast, with enormous, buoyant concentration. One great benefit of the speed was that there was no time to put up any ‘walls’ in collaboration—no time for ego or resistance—we were under the gun from the start.

We talked about Fosse, and I had two specific memories. First: seeing him very late at night in a black leather jacket, his arms draped over two glistening women, leaning against a grim brick wall, cigarette dangling from his lips. I was the only other one on the street, at 58th and 6th, returning from some late night work session. I see him to this day like a photograph. Bricks. Second: catching a glimpse of the set for Big Deal, one of his last works. The set was notorious among designers for having been painted totally black at the last minute at Fosse’s command. Black.

Enlarge

ORIGINAL SKETCH BY JOHN LEE BEATTY

Walter and I discussed everything, becoming great friends in the process, and thought together of the actors all being like dark city roaches crawling out of a ‘roach motel,’ that baited cardboard box you put on the floor of your kitchen in the ’70s. We were so free as to draw that together, just as we had decided that CHICAGO was ‘now.’

At some point, Walter and I were discussing juries in comic operas, the images of Trial by Jury and especially The Rake’s Progress came to both our minds. What about a jury box, and what if the writhing black ‘roaches’ crawled over and about and under it? The best “Encores” shows had one idea. ‘Visual Jokes,’ I called them, or single concepts, incorporating the now well-known “Encores” golden proscenium arch. So the jury box was framed in gold to match, like a fallen proscenium. The inside had the dark brick I remembered from that late-night Fosse snapshot in my head. There was an “Encores” tradition of ‘a conductor joke,’ a conceit that broke the wall of separation between the conductor and the performer, CHICAGO was to have that in spades. The orchestra bandstand was literally crawling with sexy dancers all in black.

And then there were the chairs—the ubiquitous bentwoods of backstage life, and mismatched as if pulled out of old dressing rooms (which some were) and painted a glistening black.

I had a theory, sorely learned about design collaboration. Of scenery, costumes, and lighting— two could be ‘virgins’ and one a ‘whore,’ or two ‘whores’ and one ‘virgin.’ To explain, with colorful costumes and colorful scenery, generally it is better to use pure white light. I had done a show where all three designs were so pulled back and so tastefully muted that we put the audience to sleep! So William Ivey Long, who did the all-black costumes, and I with my black scenery, made and kept a designer’s agreement: only Ken Billington, the lighting designer, was allowed “whorish” color. And we , William and I, were ruefully aware that our discipline would be overlooked. We knew that the one with the colorful flash would win the Tony, which actually came to be when the show triumphed on Broadway. Ken’s wonderful, often quite colorful lighting was just the right add-in to the mix as planned by all.

The New York of the early nineties was a world of black clothing. One would get on the subway and all the passengers would be dressed in black. That was in style. William Ivey Long could come up with all sorts of incredibly sexy dance clothing and it was always united by the color black—great when there was no time or money, but great for showing off the most wonderful performers.

Then came the simple ideas that ended up looking enormous. “Say, could we borrow a snow bag from City Opera? I know where there is a leftover box of silver metallic confetti!” “What about a Ladder?” Well, I said, “What about two ladders? (As homage to the actors climbing up the proscenium of Pippin, another Fosse show. ) “Ooh, ooh, a curtain for the Vaudeville Act at the end of the show—I know where there is an excellent gold sparkle curtain I designed—it’s already fireproof, we can’t wait for anything.” Years later I saw a gold sparkle curtain in a catalog (but not my four-color mix) sold as the ‘CHICAGO Sparkle Curtain’ since everyone by now knew what that meant—and everyone wondered how to get the same glittery falling silver confetti in “Razzle Dazzle.”

Enlarge

Origianl sketch by John Lee Beatty

Walter Bobbie and I were so on track together that there was no tension between us, but we knew we were on a roller coaster. One day he lost it, but only when we were hidden from others, since his joyous enthusiasm was pushing all of us forward. We were riding a wave. There was no time to make a bad decision. There were late nights and enormous unseen efforts. The stage crew and I stayed until 3 AM. You had to trust yourself and those around you completely. The same was true for the actors. Even seeming catastrophes would work to our advantage—the show was always like that, lucky from the beginning.

The wonderful thing about the minimalism of the presentation was that it made you listen—to this wonderful score—to notice the orchestrations and the players—to hear the lyrics as if new—to notice the performers and all of their gifts. In a period of musical theater when spectacle took precedence, it was so humanly, physically thrilling. And like in Fosse dancing, the smallest gesture would pay off.

The set for A Chorus Line had always been a touchstone for me. I so admired its simplicity and its intelligence. It was under appreciated, classic that it was. And had to be presented immaculately. Actually, the apparently simple Broadway version of my set for the CHICAGO revival was not the simple “Encores” set from City Center entirely. We upgraded everything, including adding an elevator, flying mechanized lights, impeccable masking, and much, much more, but most people think that those upgrades had been there always. Same thing with Walter’s direction. Envious people spoke of him doing a week’s work at “Encores” and hitting the Broadway jackpot. Not so. The entire production had to be remounted to seem just as wonderful, but he made us all do hard work on transitions, staging, lighting, props, everything. We couldn’t fake it anymore. A Broadway musical must be an unbreakable machine. Pure adrenaline had gotten the show aloft at “Encores,” now it had to be supported by steel.

So it went with CHICAGO, and often future production builders would underestimate how hard it was to build properly, or would try to cut corners. The first few iterations of the CHICAGO set on Broadway were not at all cheap, and sleek and clean craftsmanship made it zing. Later productions started to subtly cut corners, and it started to look a little tired, though a new skill was needed for something that was going to run for a quarter century; we started changing materials to survive fireproofing salts, and made panels to replace scratches from repeated touching. As orchestra members aged, or had their ears damaged, railings and panels were added. Computer-painted flags lasted longer than painted linen. A new extra durable finish on the gold-leafed proscenium and jury box trim had to survive years of abuse, as new casts were rehearsed during the day as the show performed at night. And the dancers were rubbing sensuously all over the set for twenty five years.

We then made new productions all around the world, which was fascinating as the work was so performer-oriented. Each country added its own cultural personality. The show became so ubiquitous that we finally lost track of where it was playing. The Swedish set became the German second set, or was that the one from Amsterdam? The Swedish production was the funniest and had the longest legs, and the German one played like a grim documentary about American corruption. Both productions were completely valid and completely enjoyable.

Of course, the minimalism of the show made it inexpensive to run. There were actually not many costumes, and some of them were quite deliciously ‘small.’ And the stagehand requirements were minimal as well. This meant the show, a monster hit, repaid its investment in a few months, not years. Fortunes were made from the show, which was first doubted for being “just a concert.” Producer Barry Weissler, late in the run looked at me and said: “I don’t know why I’m still paying you, there’s so little scenery.” To which I replied: “That’s exactly why you are still paying me. You lucked out.” We all did. What is still joyful to me is that it is an excellent show—it always was.

We were critically lauded as the antidote to falling chandeliers and flying helicopters.

“Encores” thrived as well for many years and beyond, and I left after 69 (?!) shows. The great success of CHICAGO was both a blessing and a curse. People came to think “Encores” was a try-out house for revivals, which wasn’t true even back when we did CHICAGO. What had been dismissed as a glorious concert, the Weisslers risked picking up and enhancing to move. Directors would ask for more and more, based on the enhanced Broadway CHICAGO set, misremembering the original “Encores” concert version.

Musical theater is a very serious business in New York City.

Given that, the “Encores” series should have budgeted more money, and the long-time tenure of the series proved the original “short-term community celebration” production conceit a lie. These popular shows became longer-running, longer-rehearsed, and the original book-in-hand look became contradictory when more costumes and set changes showed up.

Philosophically speaking, the change in public perception was inevitable. Curiously, only three or four more shows I did at “Encores! ” moved to Broadway and were a bit painful to watch, as the minimalism that producers so loved financially, wasn’t as artistically pointed as CHICAGO’s. On Broadway these revivals just looked under-budgeted. Critics noticed. An orchestra seated onstage meant you could sell more seats in the auditorium, but the layout wasn’t nearly as justified as it was in this production. Producers envied the CHICAGO miracle. But it couldn’t be repeated.

Enlarge

Photo by John Lee Beatty

For the twenty-fifth anniversary of CHICAGO we added a sparkling show logo to the still existent minimalism, and also a flying electric sign for the finale. We had added the electric sign of the by then familiar logo to a surprisingly good cruise ship version(!) of CHICAGO and the glittering Broadway show curtain respected the CHICAGO color scheme for the age of the ‘selfie’ background. Even I myself took a picture of the logo as I sat waiting for the show!