Just before he died, my old friend Melvin Bernhardt and I met to have one last lunch. Among so many things, we discussed a great conundrum of collaboration by a director and a designer. Crimes of the Heart, by Beth Henley, directed by Melvin Bernhardt, started its New York life at Stage Two of the old Manhattan Theater Club on East 73rd Street. Stage Two was really just a platform shoved into a corner, and it had no wings, no flies, no proscenium, no exit from the stage except down a stairs into the basement. And, of course a big column in the middle of the seating bank, which you were supposed to ignore. It was the room in which I had made my New York debut, designing sets and costumes for Marouf, Cobbler of Cairo a story theater presentation.

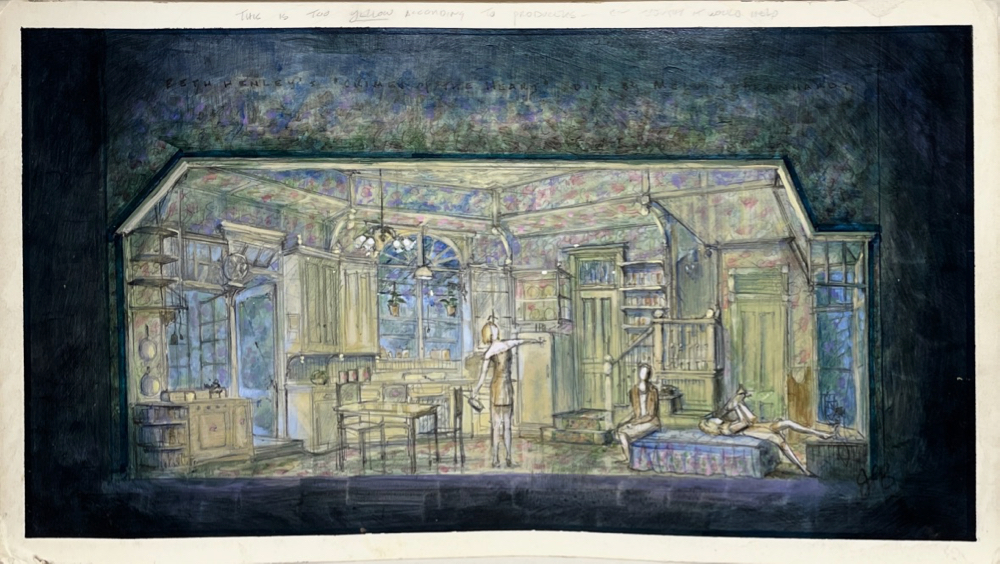

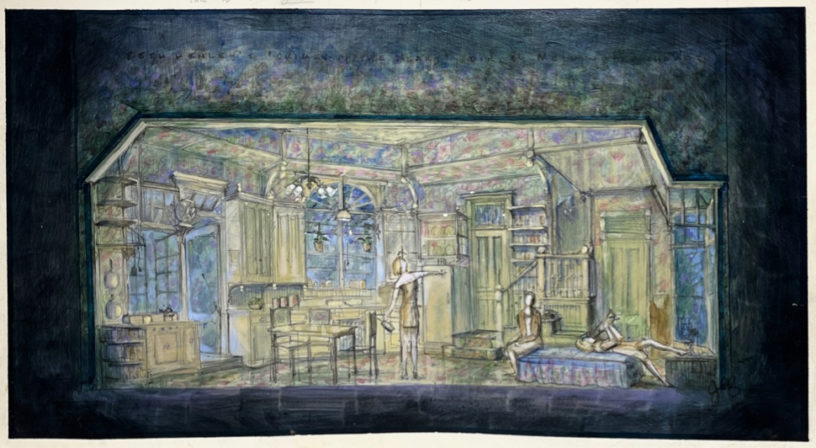

You have already guessed correctly that there was no budget. That always come with doing new plays. Having already worked in the room, and the Theater Club having some wonderful carpenters and property people, the set was an amalgam of new and old, inexpensive floral linoleum, used cabinets, leftover wallpaper, you name it. The budget didn’t allow us to build doors, so I made a scenic joke by pulling used doors by designers David Jenkins, Santo Loquasto, and Tony Straiges — which to my horror, I then had to copy when the show became a huge hit and we moved to the Golden, on Broadway. The good news was that the Golden Theater on Broadway had the smallest stage on Broadway and the constricted backstage space at Stage Two revealed itself to have been our friend when jamming the new set into the similarly constricted backstage of the new theater.

Melvin Bernhardt, a Tony award-winning director and also a great friend of mine, first called me about doing the play. He said it had a wonderful, slightly off-beat Eudora Welty Southern gothic quality. Eudora Welty’s books were in our living room as a child, and the color scheme of the set was suggested by my memory of the book cover for Welty’s The Ponder Heart. I also brought memories from a visit at eight years old to my great Aunt Becky’s kitchen in rural Tennessee in 1956. That was a sense memory to build on. It was 1956, but it might as well have been 50 years earlier.

The set description by the author didn’t make complete sense to me, as a bed was in the kitchen, and ground plan logic was not in abundance. So I decided to let it be a bit of a collage, a bit of a fantasy, but a detailed southern kitchen nonetheless. My design was not insincere.

So there we were years and years later, Melvin and I having a long lunch together just months before he died. Our question to each other about this enormously successful, award-winning hit play was based on this:

Beth Henley told Melvin that she hated to classify the play as ‘Eudora Welty, wacky southern Gothic.’ But that is the world that he and I created. And Melvin’s first words to me had stuck. Permanently. Beth was not very keen on the set, and my collage of cabbage rose wallpaper, printed organdy, and linoleum was true to its intentions. Which were not hers, apparently. The big conundrum was that the production succeeded mightily in the manner that Melvin and I devised. So did our supposed misinterpretation make it succeed, or was it going to succeed another way? An interesting question.

Melvin never worked with Beth again. I did, twice more, through ever-faithful Manhattan Theater Club auspices, doing The Miss Firecracker Contest and The Lucky Spot with other directors. But she wasn’t happy with the Crimes … set, and the sketch has some color notations for revisions made in response to her and the many, mostly female, producers. After the final paint call, with critics coming to the evening’s performance, the manager called me at home as I was dressing to return for the critic’s performance. Sweetly acidic in tone, she wanted me to know that the playwright was still not happy with the painting of the set, and what was I going to do about it? Seeing as the critics were arriving, and no one in the Broadway of 1983 ever paid for another paint call anyhow, I asked what was I to do? She said she just thought I should know that the author was unhappy. Note taken.

But was the production maybe wrong in the right way? A great success, the play ran and ran and ran. And is unhappiness a good note to give?

Beth Henley’s next production, directed and designed by others wasn’t done in that style and was a ‘happy’ show. And it also closed in under a month.

Melvin and I pondered, “Is an act of outside interpretation or misinterpretation an added value to a new play, or were we simply wrong? Did we ‘make’ the play or ruin it?”

A conundrum.

Enlarge