I was told to stay in the lobby. I was 27 years old, but was really a boy designer in show business terms. A cloud of curly red hair, blue eyes, tall and skinny — I looked like I was an innocent, goofy college boy. I sat in an oversized lobby chair at the old Versailles Hotel, now long gone, a favorite of theatrical agents and visiting theater royalty. The royalty was upstairs. I was left alone below.

Harold Pinter was auditioning set designers for a revival of The Innocents, an older play based on Henry James’s “The Turn of the Screw.” Pinter was directing, not writing. I assume I was asked to come by as a rising (and inexpensive) young designer. I had done one Broadway production, but still I had no clue as to why I was asked. Harold Pinter had never heard of me. I showed up, as one did in those pre-electronic days, with my large portfolio which held all my hand-painted designs. ‘They,’ the unnamed people running the interviews, looked at their watches and told me to hand over my portfolio to them and that it would go upstairs without me. I resisted. There were no copies of my work — that was it. Portfolio lost, and I would have no career. But up it went.

Harold Pinter, it turned out, was embarrassed to talk to any designer whose work he didn’t like. So all portfolios went up alone, he looked through them and then gave word if the designer were to be summoned up to the suite.

Boy designer was summoned. Harold Pinter, a famous man of the theater, great writer, sat in the suite. He was quite calm and polite after a quick glance at me, ever so slightly amused at the situation. There was an audience of three ‘theys’ watching us chat. He liked my work apparently. I spoke a bit about it, and about Henry James. I was as usual, shy and a bit diffident. It was not a long conversation. I retook possession of the all-important portfolio and left.

The phone call came from Harold. He had a deep resonant baritone. In my innocence I didn’t even know he had been an actor, let alone a director. We didn’t have Wikipedia back then.

“John, would you be so kind as to design my production of The Innocents?

“Oh sure.”

He was going away for a bit but would come back. This was a rather out-of-body experience. By the time his formal invitation actually sunk in, I was carrying the portfolio down 8th Avenue in the forties, and started to cry. What was this that was happening to me? He told me later he liked my portfolio best. Okay. Wow. Harold Pinter.

He was surprisingly easy to work with. I would ask an idiot savant kind of question and he would answer gravely. I asked him how the actors would move, and, slightly amused, he showed me how a scene would be played. To me it was everything, so helpful — it was like in a Pinter play, straight and deliberate. Once he asked if there were curtains on the manor house windows and I said “Oh yes, They’re brown.” “Why?” “I don’t know, Harold, but they’re brown.” He accepted my designer instincts with a small smile, and wasted no time questioning more. A favorite answer I remember was to my question about the ghosts in the play — “How were we to show they were ghosts?” “Ghosts look just like us. It’s only that they’re dead.” Very matter-of-fact. Harold’s observation on ghosts is quite true in a few of his own plays as well. Exciting.

The tantalizing idea of Harold Pinter’s take on James’s “The Turn of the Screw” rather crashed on the rocks of the Archibald adaptation we were doing. I arrived in London where we rehearsed during a freakishly hot summer when the grass turned brown and leaves drooped and fell in Berkeley Square. The rehearsal furniture for the setting, an English manor house, was far better than what we could find for the real show in the States. I worried about that. But the real problem was announced to me privately by Harold in his sonorous voice. “John, I accepted the direction on the basis of the film not the stage script that we are forced to use. I don’t know what I am to do. They will only allow small cuts.” Yet on one day of rehearsal, two sheets of paper mysteriously appeared, covered with lines in small writing. It was just a small scene he adapted, but if only he could have … I always wonder what happened to that piece of paper. No one acknowledged the obvious, that Harold Pinter wrote it. Claire Bloom quietly read it and continued to rehearse.

Claire Bloom was the star. Riding on some recent successes, she was beautiful, even more so in person than in films. She was intelligent and well-mannered too. In my American innocence I didn’t realize that she and Harold were both Jewish as well as English. In that innocence, it didn’t register to me that one could be both. This was quite a meeting. Harold, handsome and always well-dressed had oddly never met beautiful Claire before. He did so now.

Claire, Harold, and boy designer John went off to a tea room opposite the British Museum for some tea. All three of us sat down to discuss the other works of Henry James. As an English major and a compulsive reader, I had read all of James except “The Bostonians.” Good thing, as I could keep up. Claire got up to “make a phone call” though she headed to the back of the restaurant. Harold followed her with his eyes and in his baritone said, “You know John, Claire is a damned beautiful woman.” Yes, she is — I can only imagine the impact both of them had on each other. She was with Phillip Roth at that time, and Harold was on the run from his overly tabloid-observed divorce. I wasn’t enough of a grown-up to have a clue about anything. Their kindness to me sometimes seemed a conduit for some other kind of discussion but that I will never know.

Harold also took me to a pub to confer with the other designers. He ordered a “Black and Tan” for me, as I had no idea how to order. This was then new to me, British production meetings in a pub. He also said he wanted Peter Quince the ghostly gardener, to have bright red hair just like mine. On the spot, I borrowed the costume designer’s scissors and chopped off a hunk of my red curls for her to match. It seemed like a good idea to do that, and Harold blinked and went on to other things.

The scenery was built in the United States, we had rehearsed in London due to everyone’s schedule. I was working in the international theater for the first time, I was discovering.

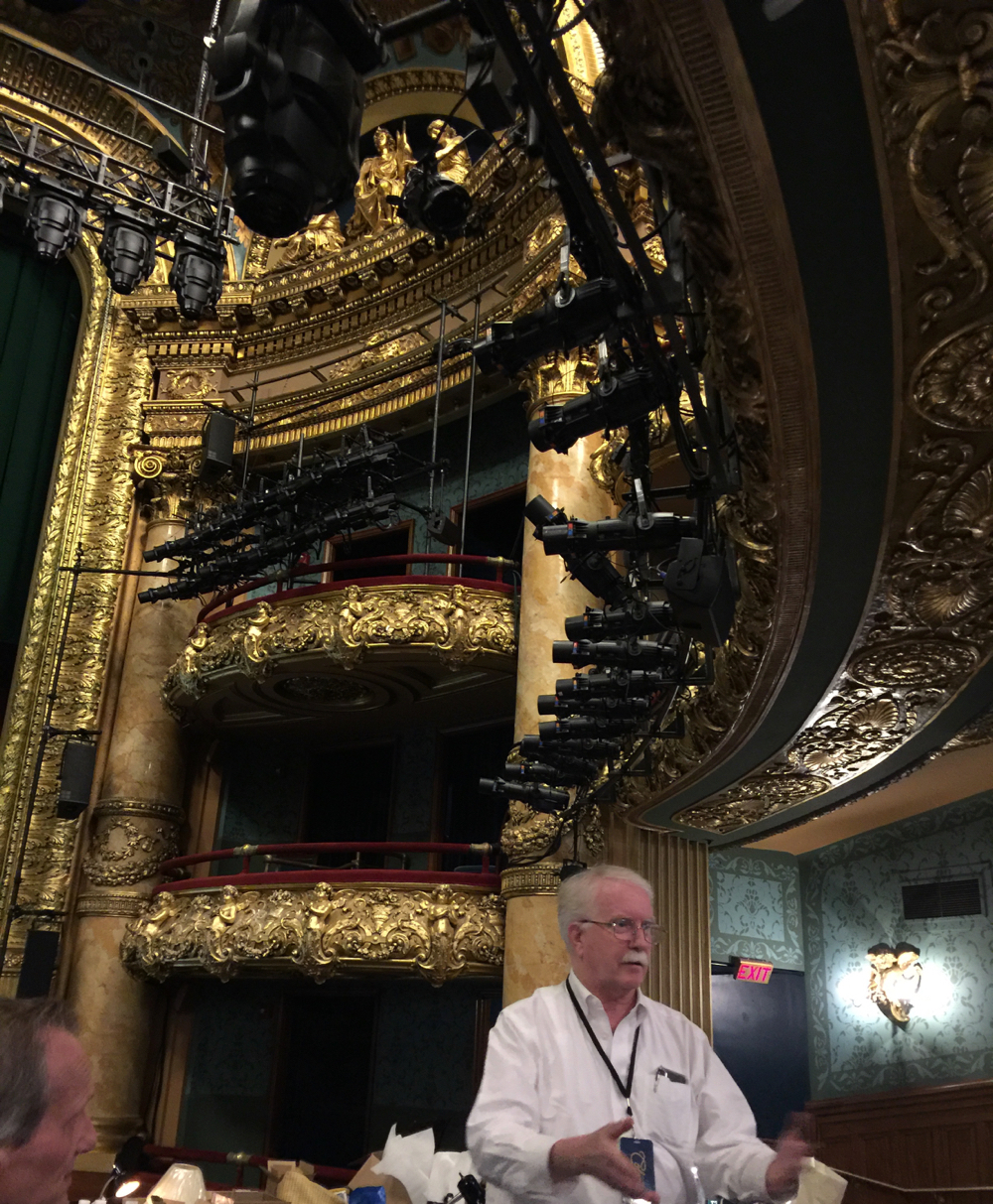

We performed in Boston, at the Colonial Theater, before the production headed to New York. This was my first, but not last tryout at the Colonial. I was scared to death and arrived at the theater way too early on the first day of ‘load in.’ An old stagehand looked me over and told me “you didn’t need to get to the theater before the scenery, son — what are you going to do, unload the trucks?“

I was nervous as could be, even having surreptitiously made an extra trip to the scene shop in Bridgeport, Connecticut to remeasure the scenery to make sure I hadn’t made some mistake. It was my first out-of-town tryout as the designer. I was getting more and more anxious as the days in Boston went by. He was coming and I was anticipating, imagining all sorts of problems. Finally, I escaped to the Colonial Theater balcony to stay out of the fray as I knew Harold was soon to arrive.

Enlarge

Harold arrived in the theater after the set was all up. Various assistants and stage managers came up to tell him of problems they anticipated. He politely shut them up and asked where I was. He turned, looked out in the house, found me, came up to the balcony and said, ”The set is very handsome John, but then I always knew it would be.” Good manners and kind. We could then go to work, my terror allayed.

One afternoon onstage, Claire Bloom showed me how to set up a proper English tea service. Of course, properly meant no one maid could carry that much china, so we edited it down, but it was a priceless lesson for a designer.

Claire had a rough day or two. She and Harold had become close, almost conspiratorial. Once he had to go to her dressing room where she had run to in distress. I have no idea what transpired. A few days later Phillip Roth came to Boston and the three of them went to dinner. If only Lady Antonia could have joined them. Wow, that would have been even higher literary octane.

Two problems, not scenic, arose. The little girl actor needed to be replaced. A very young Sarah Jessica Parker appeared to take her place, oddly familiar, as I knew her parents from working in Cincinnati. She came down the aisle ahead of her parents, and walked right into Harold’s heart. Eager to work, prepared, tiny. Years later, he would always ask about her.

The second problem was doing a tech rehearsal on a Sunday in Boston. In the British tradition, Harold expected a bottle of whiskey to be shared cue-by-cue of arranging the lighting. Finally, only beer could be found. I hope it didn’t affect the rather lugubrious tone of the show. Whiskey might have been more dramatically stimulating.

As opening night in Boston approached, Harold had clear command of the production and did not suffer interference. I loved that. He also took me to a French restaurant where I had to order in French — my fail. But we stayed on the best of terms. I had gone shopping at Filene’s Basement and found a suit by Yves Saint Laurent. I decided to hem the pants during the last note session before opening night. Harold quietly called for attention as we sat in the the gilded and mirrored ladies lounge. I sat next to him hemming the pants. I know, I know. I can’t believe I did it either. He gazed at me, amused once again. “Yves Saint Laurent, only thirty-five dollars. I had to!” Far from being incensed, Harold wanted directions to Filene’s Basement. Harold Pinter was going to shop Filene’s Basement, too. And then we did our best to fix the show.

The show couldn’t really be fixed, it turned out. It was a bit ponderous. Harold got sick, we all retreated. We all went our separate ways. I had to go on to a Lindsay Anderson directed production for the same producer. I guess I got that one since Harold had picked me and it made me good enough for Lindsay. Kind of a two-for-one of an inexpensive boy designer for visiting English directors. Difficult Lindsay I liked, but he was not tuned in to my ingenuousness.

Harold said to call him if ever I returned to England. He meant it, but I was too shy to take him up on it. He championed young David Mamet, then a playwright friend of mine in England. The next time Harold and I worked together, we both had changed. I designed an off-Broadway production of a very political play of his, plus A Kind of Alaska directed by Alan Schneider. It didn’t go badly, just not all that well. He was wondering what I had become. I wondered if maybe my boyish innocence had been a boon to him during his personal nightmares never spoken of during The Innocents. Now he was with lovely Lady Antonia, retreating a bit, and dealing with different career problems.

Years later, I did a revival of his play, the Caretaker. Now ill, he wouldn’t come to America at all for political reasons. I was a well-established designer. He was kind, clear, and trusting on the phone. He still asked about Sarah Jessica, with whom I continued to work, star that she had become. I wondered if her truly childlike innocence and eagerness had been a boon to him as well back then. Harold and I briefly spoke of Boston and our time together, by then 25 years had passed. By 2003 I wasn’t a ‘boy designer’ anymore. I can still see the two of us, oddly, almost implausibly, so connected. Colonial Theater, Boston, 1976.

Enlarge

Photo by Jane Greenwood