As I sat at the breakfast table, on one of two chairs from an A.R. Gurney play I designed, a friend messaged me that Israel Horowitz, the playwright, had died. I read the obituary in the Times, and messaged back and forth to a friend, adding at the end with “I designed two of his plays.” My friend was surprised. I was a bit surprised myself.

I returned to the crossword and a cup of coffee. It was Thursday, so the puzzle was getting a bit harder. I decided to skip around and do the easy ones. One was “Tandy” for Jessica Tandy, the actress who first played Blanche duBois. Easy for me. Very easy. And I had worked with her, not on Streetcar … but Foxfire in its first incarnation at the Guthrie. No one would remember that either.

Two movies on TCM the day before had James Mason and Fredric March. Even I was suddenly surprised in the middle of watching to realize I had known them. The math wouldn’t really seem to indicate it.

A week or so before, the Sean Connery obituary mentioned a film with Gina Lollobrigida. Yes, I knew Miss Lollobrigida in a long ago life.

As I walk across my living room, I tread on the art deco Chinese carpet walked upon by actors and directors long gone or still here, passing the sofa sat upon by Cherry Jones in The Heiress. And I avoid my gaze in the mirror previously gazed in by Faye Dunaway in Curse of the Aching Heart.

And my friend had sent a campy picture from the 1940s the other day. I asked him who it was and he looked it up and said June Havoc. It was really quite funny when I remarked, “I worked with her, too.”

Not my friends, not even I, realize what a busy designer might witness. And the designer’s code of silence about bad behavior remains, easy to maintain as we are forgotten silent witnesses, seldom asked.

Herewith some stories:

JESSICA TANDY

Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy were an acting institution. He was the promoter, the author, the producer. And sometimes the busybody. She was the quiet observer, vigilant. The notes came from him. He summoned me quite politely to come to their suite in the old Wyndham hotel. A pleasant suite apartment for them to live in when they were not ‘on the road’ and rented out other times. The staff knew them, and they often entertained in the hotel dining room, or had dinner brought upstairs.

I was shown up to the suite and graciously greeted. It was a matinee day, so Miss Tandy, having arisen from the briefest of naps was at five-fifteen, being served a tea and a scone (or was it a crumpet?) with napery and silver on a lovely plate, as per usual on a matinee day. A quiet, friendly greeting was offered. Hume and I continued on the carpeted floor with our ‘informal look’ at the set design (‘informal’ meaning, noticeably to me, without the director’s presence.) Hume was testing me a bit for my ability to hear and take his notes as he opined professionally about every aspect of the production.

Hume was wondering if the rural southern sky should have electric stars included. I said I couldn’t, having just won the Tony for Talley’s Folly, say they didn’t work, but that since this setting was slightly less literal in intent, that maybe the effect might be a bit ‘Disneyland.’ Hume wasn’t sure he agreed. Miss Tandy said softly, “Hume, I do think young Mr. Beatty (English pronunciation) might be right. After all, I can act stars.”

At which point the tea cup was placed in its saucer, the napkin was touched her lips, the Chippendale chair was pushed back, and Miss Tandy went to the center of the room. She held out her arms and most importantly and amazingly — did not look up — acting ‘stars’ for Hume and me, on the floor at her feet.

Miss Tandy returned to her afternoon tea, Hume looked back down at the drawing, and said, ”Right, no electric stars.”

Far later into production at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, our play was making its debut. A particular Thursday was firmly scheduled for an ‘impromptu, informal dinner’ with Tandy and Cronyn at their hotel. In the dining room, coat and tie. Don’t be late. A lovely meal. A small bit of tension in the air, as Miss Tandy worked in her own way, and the director, Marshall W. Mason worked in another. A truce had been arranged, and she was well on her way to creating a remarkable performance. So interesting to see that she didn’t ‘put on’ the persona of a rural Tennessee grandma of the hills, but gently softened all the qualities she didn’t have in common with the granny, and heightened the ones she did have in common. A fascinating, but private process sometimes leaving the rest of us a bit shut out. But remarkable and true.

The esteemed actors were more than a bit distrustful of the young director’s methods and background, so he chose to discuss classical theater instead of the project at hand. A good idea in theory, but perhaps rather deep water to enter with two such skilled swimmers. Blithely going forward, Marshall started speaking of Hamlet and its various productions, Circle Rep having recently done its own. “So many Hamlets to compare, I was wondering what your opinion might be of the difference between Gielgud and Evans.” In Miss Tandy’s eyes, tiny little sparkles of excitability appear. I try to lead the director astray by saying I had once worked with Maurice Evans, but forcefully we return … “Did you by any chance see both of them perform the role?” “Did you see Gielgud?”

Miss Tandy was enjoying her gravlax appetizer, but was soon to enjoy herself even more, “I would so love to offer you an opinion, but you see it would be so difficult … since I was Gielgud’s Ophelia.”

Delivered so well. So very well. Such deep water.

I chortled a bit. She looked grave then burst into delighted peals of laughter — bullseye!

FREDRIC MARCH

I didn’t really know him. But he looked a lot like my father, and was a famous, famous actor.

He was standing at an opening night party at the ballroom of the Piccadilly Hotel. I was a young assistant designer on my first Broadway show, seated at a long table for the ‘unreserved’ in the company. The show had opened and now a curious quiet was soon to descend on the ballroom. I noticed the producer downing a large platter of food, oblivious to all, intent on his noodles. Doug Schmidt, my delightful employer, informed me what that meant — the producer wasn’t so sure where his next meals were coming from as he had an inkling of the evening’s results.

Fredric March stood impassive, tuxedoed, flanked by his wife, stage actress Florence Eldridge, on one side, and a most beautiful movie star, Paulette Goddard on the other. Miss Goddard was in a winter white mohair knitted sheath, figure revealing to say the least, if you could get past the remarkable emeralds around her neck. Miss Eldridge didn’t have much of a chance, but then one felt that had always been the case. They were all older than I could compute on my fingers, but what a vision. It was 1973. They had seen it all, been seen by all. They had seen openings, they had seen great success, and great failure. They were beyond reach, standing as a trio of history. Garbo, Chaplin, O’Neill, Wilder. They never sat down, they stood still. I looked up again and they had disappeared entirely.

CHERRY JONES

She practiced throwing her skirts and ascending the long staircase every night. Like an athlete. All worth it. On this production of The Heiress the elements had all preposterously fallen into place. A stage star had been born. Cherry Jones was seen. Long work before, of course, but this one production made a star. They said it didn’t happen anymore. But it did, and she was ready.

As I mentioned, at every half hour she practiced throwing her skirts about and ascending the long staircase.

ANN REINKING — Dancing in High Heels

The last time the entire production team (musical director, director, choreographer, scenic designer, costume designer, lighting designer) of the revival of CHICAGO was together at the same time, was for the Australian production. To honor that occasion we assumed the pose of the showgirls in CHICAGO. Ann Reinking, our choreographer, and our first fabulous Roxie, arranged us in Fosse poses and joined us. The photographer was scrambling to catch the photo, and dropped some equipment, so we had to hold the pause far longer than intended. Through clenched teeth I said, ”This really hurts!” to which Ann replied through her clenched teeth and brilliant smile, “It all hurts!”

Those minimal Fosse style sleek and sexy movements all hurt one’s body … Ann was often in pain, and had back problems that were the stuff of legend. You never knew it from out front, where she was an elegant, sinuous, long-legged dynamo.

A truly professional dancer, and a completely professional ‘babe,’ she forever impressed me when we went into performance. She had rehearsed in running shoes, tights, and an old baggy sweater. She had been busy choreographing, dancing, advising, inspiring, while still maintaining a slightly preoccupied demeanor. Come the final dress, with the audience present, she transformed into the complete vision of a babe: dark hair pulled back, flashing eyes painted, cheekbones enhanced, her long legs encased in silky stockings, and wearing four inch heels. Dancing in four inch heels, climbing ladders in four inch heels, for the first time, in front of an audience. Wow. She, of course knew that a woman in heels actually never touches the heel to the floor, which must have only added to the pain of performing the apparently ‘easy’ Fosse dancing. She was already in pain from a back injury — not that it would ever show. It all hurts!

FAYE DUNAWAY — Returns to the Stage

There must be a time in a beautiful, successful actor’s life when she is faced with a choice of either pulling back to safety or allowing the raging currents carry her over Niagara Falls. It was clear that Faye had taken the latter route.

Faye decided that she wanted the leading role in The Curse of an Aching Heart by William Alfred. She wanted to play the young working-class girl from Brooklyn, first discovered on roller skates in a back alley, and speaking in verse. Having appeared in Mr. Alfred’s Hogan’s Goat it was not too hard for Miss Dunaway to appear at his professorial home in Boston at teatime, sit on his knee and lobby for the part. That neatly accomplished, she had to convince the rest of the production, especially the director — who was close to the designer — and me.

A campaign was waged. A little informal dinner was proposed. I was teaching at Brooklyn College at the time, good for researching the play, but on the night of the supper, I was horrifically late due to a student’s problem and called the great star from the Brooklyn subway. She was most sympathetic, charming, and worried horribly about the student’s crisis. That seems odd, but lovely. I made it to the dinner.

Director Gerald Gutierrez whispered to me, that Faye had done her investigative homework, ascertained that we were friends and that she had to convince me that she was right for the part. Especially that she was young enough . She was a huge star, older than 31-year-old me, and wanted to play a young girl.

I knew that on a previous film she had bribed a chauffeur to let her replace him for a day to prove to the powers that be that she could pass as a man, revealing at the end of the trip, that it was “Faye.” She didn’t really make such an effort for us, dressed as simply as she was, and going out for a quiet, modest dinner, in an unpretentious restaurant. I must confess I kept counting on my fingers under the tablecloth, as she seemed to be my age, if not a little younger, but I recalled seeing her on the cover of Time or Life when I was a sophomore in University. How could that be? Did she start so early? A simple sweater, a plaid woolen skirt, her hair loosely down. She was demure and charming, the effect only upset a bit by a screaming fit from her partner including his throwing her credit card at her in front of us all.

The producers were game to have her, as she would have marquee value, and so the die was cast.

The Faye that showed up at the working rehearsal was fully seven years older than me, and quite intent on all aspects of preparation. She wanted to rehearse long hours, was going for exhaustive roller-skating lessons, and extremely intense costume fittings.

The costumes oddly started out as working girl clothes but soon morphed into flowing silk chiffons with picture hats.

The complicated revolving set, complete with streetcar, was carpeted all over in a caramel golden brown. Or at least it was going to be … I knew from a previous show that skating on carpet gave a “slo-mo” effect useful on stage, but..the day before it was to be installed Faye told us that she had consulted her skating instructor, and it had to be battleship linoleum. And must be changed. I allowed as how, for stage the carpet was best, as it slowed down the roller skates. The director said there was no time, it was to be installed tomorrow and it needed to be butterscotch color for the images to work.

I do admire Miss Dunaway, as she got on the phone. She called all over New York, and her last call was to a battleship linoleum warehouse in the Bronx.

“Is this Vito? This is Faye Dunaway.”

Laughter and then “Yes, Vito, ha ha, the movie star … Why yes, Vito … (lower voice ) Why, thank you Vito, that’s … very nice of you.” “Now Vito, I need some linoleum … ”

A limo was dispatched, a sample to be brought to me, and , yes, Vito got it to her in butterscotch brown. Bless her for the follow-through. She got it done. She could have left us hanging.

The curtain rose on first preview, Faye skated out quickly, too quickly, and fell on her ass.

But I admired her for her perseverance. She didn’t walk away from some heavy-duty linoleum shopping, no matter how the story ended. She wasn’t really right for the part, too mature, too elegant. And, bad news for the producers, she wasn’t the kind of movie star that sells more than three weeks of tickets.

We all sank quickly. I’m not sure the set was completely right either, linoleum aside.

Sweet, strange play. Gone so quickly.

JUNE HAVOC — A Dressing Room

We were out of town, trying out in Philadelphia. It wasn’t going badly, it wasn’t going well. Trying out in Philadelphia surely was not unfamiliar to June Havoc. Obviously to a theater person of my age, she was the actual Dainty June of Gypsy in her past life, but I knew her to be a ‘survivor’ type, an animal lover, and an actress with a strong resume. But time was passing, and show business was leaving her behind.

Stuck in the theater sixteen hours a day, I had some time on my hands after supervising notes and calling back to New York, a feat accomplished by lining up, coins in hand, to use the single payphone backstage. Waiting my turn, I wandered the deserted dressing room hallways. As no one was around, I tip-toed into Miss Havoc’s dressing room. And into a time warp.

The sadly cramped room was hers alone, as she was a star, but it ended about there. A small opening in the brick wall was a window to an alley that let in no light at all. But it was the dressing table that fascinated — it had a clean, faded terry towel spread across it, a lined up row of grease paint makeup, obviously in her colors, cold cream, powder, makeup pencils, and a miniature frying pan set on a stand over a very small oil lamp, next to it a black wax crayon, and a little jar of wooden kitchen matches. She clearly made her own mascara effect by taking the black melted wax and individually applying black wax beads to the ends of each of her lashes, applied with the end of a wooden kitchen match.

The bentwood chair at her table had a towel and a floral kimono, a pair of slippers on the floor under the table. Neat, purposeful, and every single item out-dated, or soon to entirely disappear, from the world of theater. Soon Dainty June was going to have a hard time finding those wooden kitchen matches, too. Like Miss Havoc, they didn’t make them like that anymore …

MISS LOLLOBRIGIDA

I was the set designer on the supposed revival of The Rose Tattoo starring Gina Lollobrigida, to be directed by Joey Tillinger and produced by Harry Rigby, a charming if scattered gentleman. We had all sorts of meetings. A reception at a hotel, etc. Miss Lollobrigida was quite beautiful and charming, but not the most trusting of stars. One time she opined under her breath that she wasn’t sure Christopher Atkins (of Blue Lagoon heartthrob fame) should play her daughter’s virginal boyfriend as she had suspicions that he was not actually a virgin! She eyed him, not sure of him at all. Not accustomed to the theater, she had on her own, as she said was traditional in Italy, solo character photographs made of herself far in advance of the production, costumed as Serafina, which she presented to us. A surprise to the producer and management, the costumes, which weren’t at all right for the American Gulf Coast, were, I believe, made by the Fontana Sisters in Rome, who were quite, quite famous for dressing many post-war movie stars. One had to be a bit diplomatic with Miss Lollobrigida. One didn’t mention other Italian actresses at all, such as Anna Magnani (who had been in the film) or God forbid, Sophia Loren. I think we were coached on that.

The tour was to start somewhere, possibly Baltimore, and go across country on an old-fashioned road tour, and then to Broadway. We had no idea if she could pull it off. She was unfamiliar with touring America as a concept, big American auditoriums, etc, and was trying to wrap her head around it. I myself was quite concerned about the complicated scenery as there was no way to carry the palm trees (mentioned so often in the script) to so many quick engagements, but a much bigger problem presented itself. I then discovered that Miss Lollobrigida wanted to be paid for the photos and she wanted to be paid for the (expensive) costumes and to use the costumes in our show. She had a penchant for turning in bills it turned out. And a (union) American costume designer had been hired already. An Italian brick wall seemed to have been erected.

One Sunday afternoon I was phoned at home. “Meester Beety? Thees ees Meees Lol-lo-bree-ghee-da” and we were off to the races. She wanted me, the set designer, as her last resort, to convince the producers to pay for her Italian costumes, and to tell them firmly that they were worth their price and were absolutely perfect for the production. She didn’t, or wouldn’t, understand how we functioned here, and our hour-long discussion did nothing to dissuade her of her notions.

It all fell apart soon after, and to my horror months later, famed agent Lionel Larner came up to me at the Berkshire Theater Festival opening of a play I designed, and with great courtly good manners introduced me to Carroll O’Connor and his wife, and then flatly stated that my lack of approval of the costumes had sunk the entire production and that Miss Lollobrigida had departed. Mr O’Connor and his wife’s eyes popped a bit. I was a bit shocked, as I was still a boy designer and knew that the story couldn’t have actually been true. Harry Rigby and management had tired of her ‘requests’ and, I think, used the issue as an excuse. As Harry often said, “She isn’t Debbie.” By which he meant, she wasn’t his beloved Debbie Reynolds for whom all (including extraneous bills) was worth it as she sold so many, many tickets.

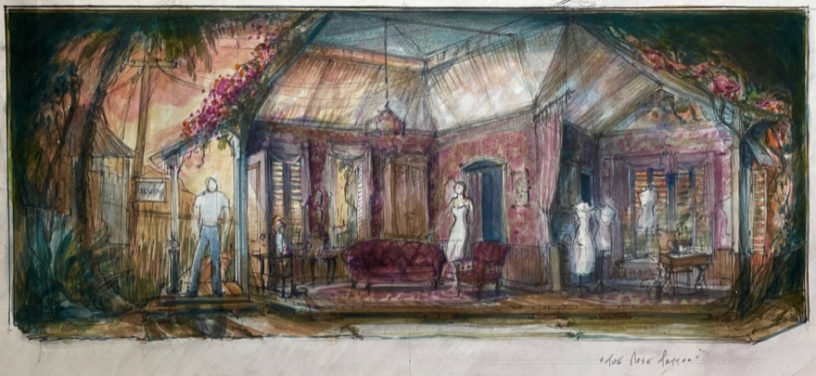

So the play never got on at all. I still have the sketch.

Harry died soon after. I went to the crowded afternoon funeral at Frank Campbell. Ann Miller made a late entrance, “The Mick” (Mickey Rooney) had sent a big blanket of flowers, and the composers of a “Treasure Island” musical that Harry was supposedly producing sang quite a few of the songs, and it became for awhile a backer’s audition intended for any remaining live producers in attendance.

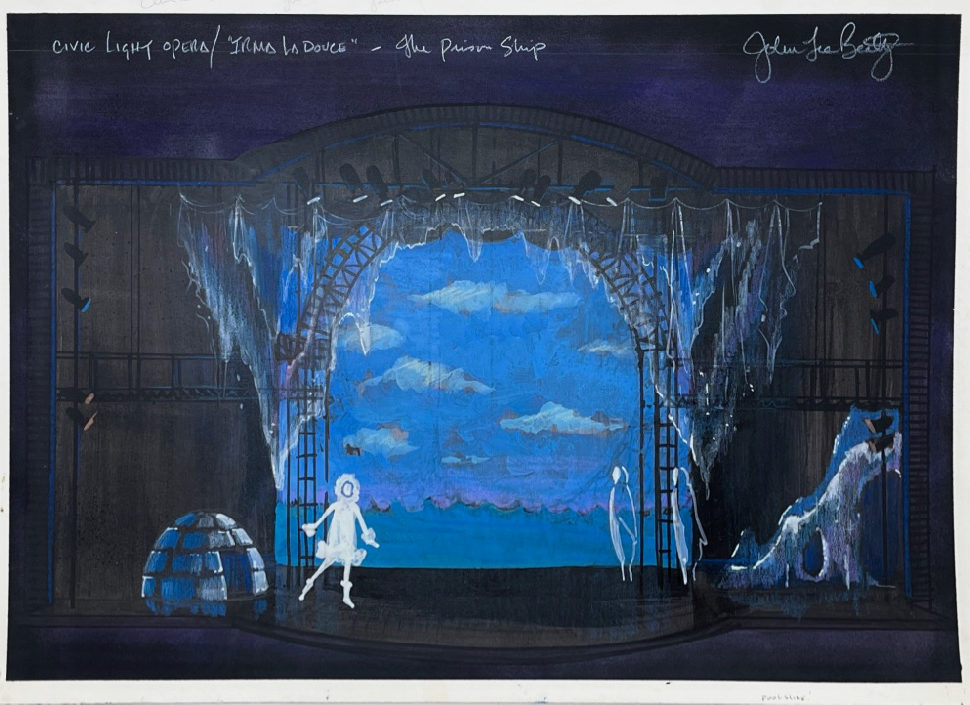

Enlarge

Scenic Rendering by John Lee Beatty

MICHAEL KIDD

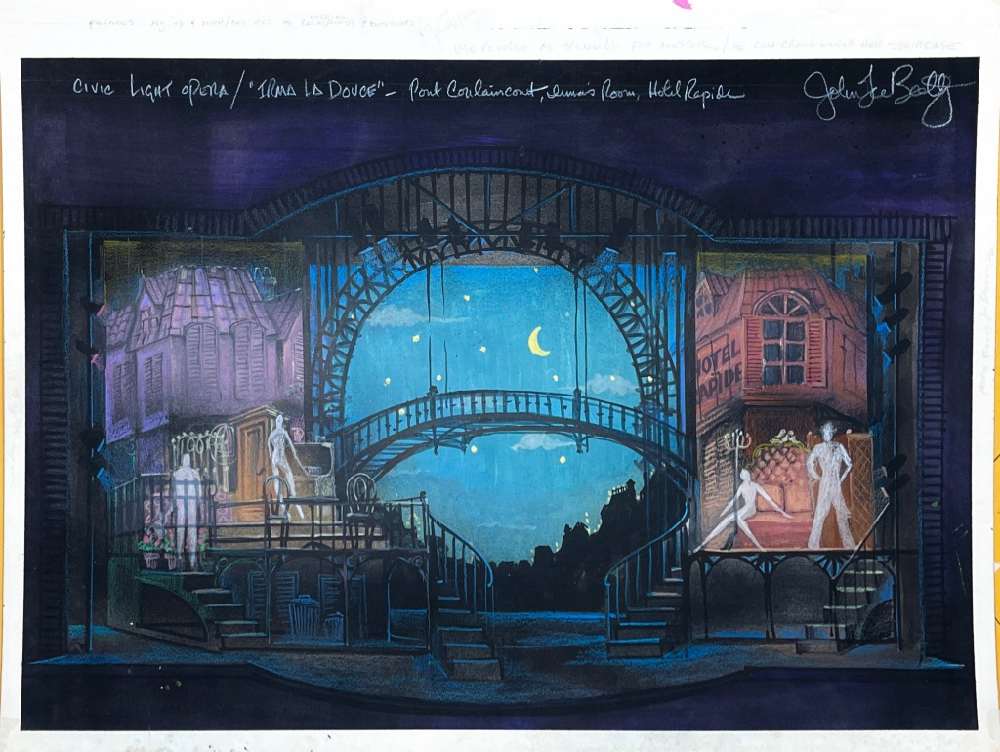

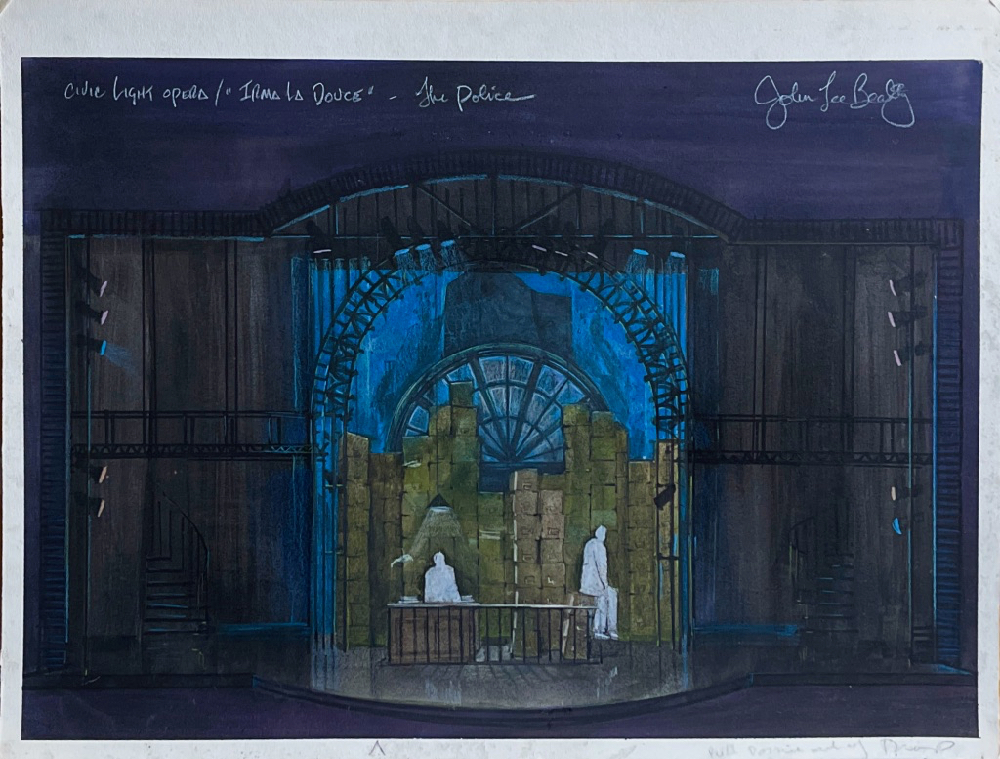

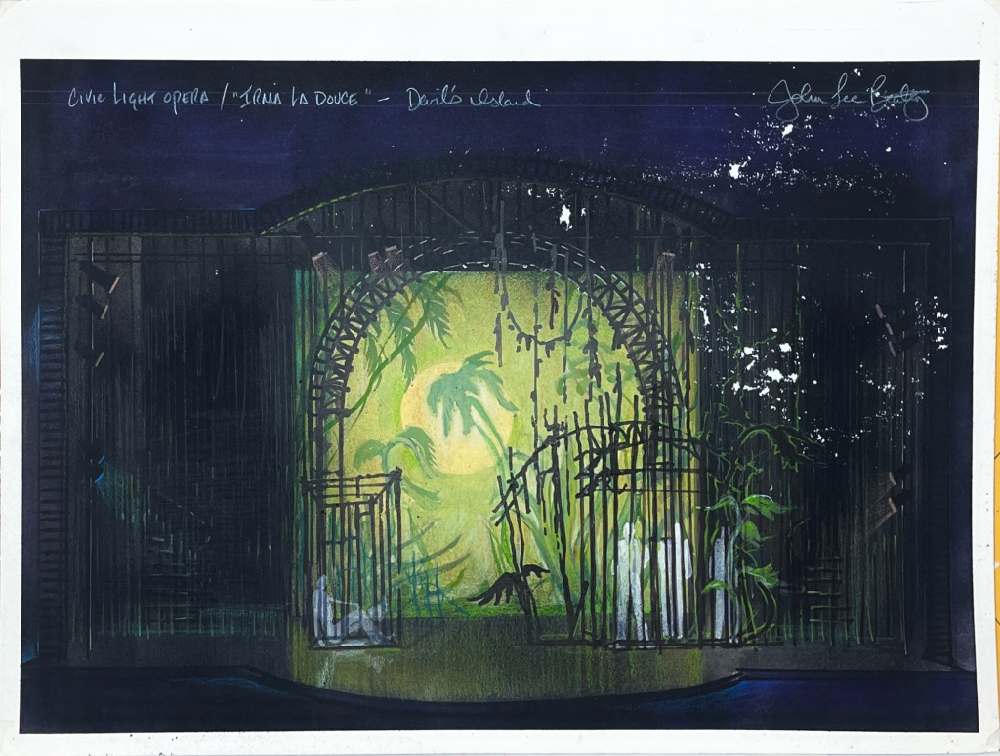

I was asked to design a revival of the musical Irma La Douce for the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. It was to be directed and choreographed by Michael Kidd, produced by legendary producers Feuer and Martin. It was 1977 and I was 28, newly arrived on the scene. What was wrong with this picture?

The Civic Light Opera was where many childhood theater going memories began, being a Southern California boy. The offer was hard to resist, and close to home, where I would see my parents as well.

The offer was also too good to be true, and far beyond my experience, though I had just barely been on Broadway by this point. The truth of the matter revealed itself in my meeting with Cy Feuer, ”We wanted Tony Walton then couldn’t find anyone else.” Well, at least that made sense. I should have realized an offer that was too good to be true was one to avoid. But as ever at this point, I trusted these wildly experienced older theater people to know more than I did. They had created Guys and Dolls after all, which was the only musical acceptable at Yale School of Drama that wasn’t Brecht/Weill.

I thought they knew something I didn’t — as well they should. It didn’t really make sense that I started the designs with Cy Feuer, the producer, instead of Michael Kidd, but that’s how he wanted to do it. I kept worrying about how Michael Kidd would feel. Mr Feuer had directed some himself, and ‘doctored’ his own and other shows. It seemed out of balance meeting with him, and I really was confused since the show, which I had designed once in a small summer stock production with Donna McKechnie, was famous for being one woman and twenty five men, but now was to have six showgirls from Las Vegas, and a full male and female dancing chorus as well. I came to see that this idea was from producers Feuer and Martin, and that was how their musicals were put together.

It all seemed a bit off to me, but, as ever, I was working with legends — and they must know what they were doing. I certainly didn’t.

I landed in Los Angeles with the designs so far, and headed to the very nice offices at the Music Center. I was stared at by one and all, it must have been my youth, and promptly fell into the role of tenderfoot. The situation was to be complicated. The production was by being lit by Robert Randolph, famous set and lighting designer of the sixties, though oddly not doing the scenery for his old producer friends this time. At the same time he was trying to take over managing their shop where the scenery was to be built.

All sorts of Broadway types showed up. I recall agent Ira Bernstein being greeted by at least three people in a row saying “Hello Ira, how’s Florence?” I had paid enough attention to know he was Florence Henderson’s husband, but I did wonder how he felt hearing that opening every time he entered a room. Odd, since it had nothing to do with our show.

Finally Michael Kidd showed up, met me, and with a minimum of small talk I was to present the designs to him. In front of all. That didn’t seem right to me … and it was an ill-thought-out public disaster. He said bluntly that the designs wouldn’t do. Suitably embarrassed in front of all, he and I were shunted off to a small office alone.

Michael was tough, direct, and oddly kind. I immediately picked up that he didn’t hate me, in fact, a reality check was in progress. He knew how these producers were working, accepted it without comment, and now we were getting down to work. I wish we had started together, but here we were. I was under time constraints to deliver a set, so I chopped away — he said it looked too much like a nightclub show — until it looked a bit more ‘Yale.’

I was sent to a hotel room to redesign. I was frozen and terrified. I looked at art books, I looked at the wall. Something unfelt came out. Not Tony Walton. I realize now that I was thinking of the Paris of MGM movies, all while old MGM was being bulldozed.

I even had a meeting with Michael Kidd on the remnants of the Hello, Dolly! set at 20th Century Fox. He was open, down-to-earth, and quite unimpressed with his surroundings, though he had choreographed the film. He did talk about the casting of Irene Molloy in Dolly! that he didn’t agree with, that he was suspicious of, but accepted it. He mentioned something about working with Julie Andrews in Star! but nothing nasty. Just pondering the act of working on a number. He was a realist about the big collaboration that gets a show on, a bit cynical without being sour.

Our final set meeting was in the rehearsal halls after we were in process. He was working with his assistants on dance moves. He was in his element, secure, with no attitude.

For the scenery he was not forthcoming about details or concept, and surprised me later on by saying he had just read the second act the night before and what the hell were we going to do? Had he never read it before? Oh. They hadn’t prepared me for that in design school.

I suggested basing one scene on the painting Wedding on the Eiffel Tower, to which he was open, but not terribly interested in intellectual approaches. Okay. Also not like design school.

He spoked delightedly of his wonderful day off where he had installed a sprinkler system in his lawn. He loved working with his hands. I liked doing things with my hands, too.

“John, you’ve got to help me … The show has five big numbers. I can’t choreograph five — I can choreograph two, I can do staging for another, but the other two will have to be all props.” And so it was to be.

He then had to take a nap, “no need to leave, continue chatting with the assistants, John.” He leaned a folding chair against the wall and went to sleep sitting up — for about ten minutes. He woke up refreshed. Back to work.

The producers didn’t give me a car (cheap young designer to take advantage of, I guess) until the carpenters complained. Los Angeles is a big city to do a show in. We went forward. I was lost, but we went forward. Robert Randolph looked cooly at me and I realized that he wasn’t about to help me at all. He was caught, his New York career over, and I was a silly interloper to him, now possibly taking his California jobs away from him. I was an innocent abroad, I knew. He had a fifties buzz cut, I had a hippie cloud of red hair.

Eventually in technical rehearsals, I was in agony. The set was a compromise, albeit oddly, with a fairly good ground plan. The conceit being that we were in a big black backstage, we then could have Parisian ‘scenery’ show up and revolves turn with props and partial painted scenery showing our scene.

One case of ‘prop’ choreography, Michael asked me to get a pool slide, make it look like an iceberg, and let some ‘penguins’ slide down it, propelled across the stage. Fantastic idea, it stopped the show.

We rehung the order of the flying pieces every day, as Michael figured out his spatial priorities. The show carpenter who built the show was kind and old-fashioned. If there was a problem, I was supposed to describe it to him, not point it out to him together from out front. His code of behavior said that how it looked out front was my job, how he fixed problems was on his turf, backstage.

The stagehands were making lustful noises about the arrival of the tall, beautiful showgirls, who the producers had cast in Las Vegas. They arrived, perfectly pleasant, tall and stunning, and the stagehands ran in the other direction and all got a crush on a little dark-haired chorus dancer. The chorus members explained that to be a Las Vegas showgirl one had to get the exact breast implant required for work, but that the job involved little real show dancing. It was hard to remember why they were there.

The dancers worked, sometimes very physical Michael Kidd choreography, sometimes a lot of prop lifting and twirling, as promised. The props were dancing as much as the dancers. One of the stage hands wept after trying and trying to get breakaway tables to do all that Michael wanted in the bar brawl choreography. Michael sincerely sympathized with him, he loved workers, and we all went forward doing even more. There was a wonderful opening number of dancers carrying unending props, more and more, across the stage. Michael had choreographed as he promised!

There was dance scene on a revolve, backed by a wall of twinkling, exploding lights. I designed and supervised the building of the lighting effects, and Mr. Randolph took all the credit for them … “hmm. I learned something there.“ The revolve, Michael loved, but it never went fast enough for him, the stagehands finally replaced the crank with an electric bolt driver. It worked. It worked extremely well. Michael was delighted, his eyes alight as it was spinning faster and faster, but now the dancers were getting thrown off the revolve, some clasping each other in the center, ’til centrifugal force threw them into the wings. A screaming halt.

“Right.” Michael says, ”Too fast, guys.”

The stagehands’ favorite, the little wren, was off to the hospital and we pushed forward.

But Michael had no malice, only a vision.

The show eventually opened, and Priscilla Lopez, our wonderful navy blue clad Irma was dwarfed upon occasion by the sparkling Amazonian showgirls. Clever expedient ‘Michael Kidd’ staging was speeding up the repetitive second act, but nobody’s heart was in it. The show looked dark, purposely underlit to the point that even the producers asked Randolph for more light. The scenery was not always inspired to begin with, ground plan aside. I think Mr. Randolph wanted the scenery not to look very good anyhow. Mr. Randolph got the carpenter fired, and on opening night the producer dismissed me with, ”Congratulations, you have fulfilled the terms of your contract.”

Irma La Douce at the Civic Light Opera - Scenic Renderings by John Lee Beatty

In Los Angeles, my show on the Light Opera stage, I was crying in my hotel room at night. Not good enough, I thought. I suppose I learned to keep my head up, though painful. I used to punish myself by going all the way to the upper reaches of the three thousand seat theater. Fully one third of the audience couldn’t see Priscilla’s face. The scenery, sadly, they could see. I confided my pain to my mother, who with miraculously attained show business wisdom stated, “Johnny, it’s only Los Angeles. Nobody will see it.”

Years later, the Light Opera era gone, Feuer and Martin era gone, all moved on, I was approached by Michael to do another show. I looked into his face, asked how he could ever do that, as flattered as I was. I had messed up the show big time, and I liked him so much.

“Oh, John, it was fine, you are too hard on yourself, you only made one mistake.” Only one? I still wake up in the middle of the night regretting my decisions. “The masking should have been red.” In a second I realized I had neglected ‘joy’ in my design. Good note from Michael. The rest of the show’s failure? “Not your fault.” He was so matter-of-fact, saying, no problem, we are all here to work, showbiz happens, I like you.

I like you too, Michael. Workers go to work. Ignore the rest, but leave room to create joy.