I was asked to design a revival of the musical Irma La Douce for the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera. It was to be directed and choreographed by Michael Kidd, produced by legendary producers Feuer and Martin. It was 1977 and I was 28, newly arrived on the scene. What was wrong with this picture?

The Civic Light Opera was where many childhood theater going memories began, being a Southern California boy. The offer was hard to resist, and close to home, where I would see my parents as well.

The offer was also too good to be true, and far beyond my experience, though I had just barely been on Broadway by this point. The truth of the matter revealed itself in my meeting with Cy Feuer, ”We wanted Tony Walton then couldn’t find anyone else.” Well, at least that made sense. I should have realized an offer that was too good to be true was one to avoid. But as ever at this point, I trusted these wildly experienced older theater people to know more than I did. They had created Guys and Dolls after all, which was the only musical acceptable at Yale School of Drama that wasn’t Brecht/Weill.

I thought they knew something I didn’t — as well they should. It didn’t really make sense that I started the designs with Cy Feuer, the producer, instead of Michael Kidd, but that’s how he wanted to do it. I kept worrying about how Michael Kidd would feel. Mr Feuer had directed some himself, and ‘doctored’ his own and other shows. It seemed out of balance meeting with him, and I really was confused since the show, which I had designed once in a small summer stock production with Donna McKechnie, was famous for being one woman and twenty five men, but now was to have six showgirls from Las Vegas, and a full male and female dancing chorus as well. I came to see that this idea was from producers Feuer and Martin, and that was how their musicals were put together.

It all seemed a bit off to me, but, as ever, I was working with legends — and they must know what they were doing. I certainly didn’t.

I landed in Los Angeles with the designs so far, and headed to the very nice offices at the Music Center. I was stared at by one and all, it must have been my youth, and promptly fell into the role of tenderfoot. The situation was to be complicated. The production was by being lit by Robert Randolph, famous set and lighting designer of the sixties, though oddly not doing the scenery for his old producer friends this time. At the same time he was trying to take over managing their shop where the scenery was to be built.

All sorts of Broadway types showed up. I recall agent Ira Bernstein being greeted by at least three people in a row saying “Hello Ira, how’s Florence?” I had paid enough attention to know he was Florence Henderson’s husband, but I did wonder how he felt hearing that opening every time he entered a room. Odd, since it had nothing to do with our show.

Finally Michael Kidd showed up, met me, and with a minimum of small talk I was to present the designs to him. In front of all. That didn’t seem right to me … and it was an ill-thought-out public disaster. He said bluntly that the designs wouldn’t do. Suitably embarrassed in front of all, he and I were shunted off to a small office alone.

Michael was tough, direct, and oddly kind. I immediately picked up that he didn’t hate me, in fact, a reality check was in progress. He knew how these producers were working, accepted it without comment, and now we were getting down to work. I wish we had started together, but here we were. I was under time constraints to deliver a set, so I chopped away — he said it looked too much like a nightclub show — until it looked a bit more ‘Yale.’

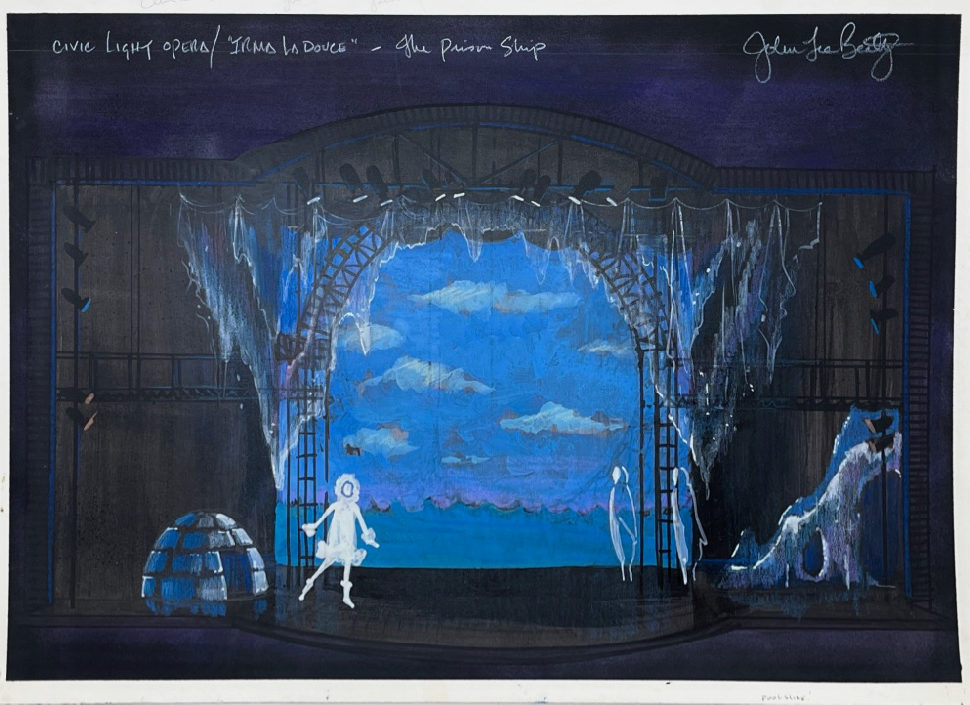

I was sent to a hotel room to redesign. I was frozen and terrified. I looked at art books, I looked at the wall. Something unfelt came out. Not Tony Walton. I realize now that I was thinking of the Paris of MGM movies, all while old MGM was being bulldozed.

I even had a meeting with Michael Kidd on the remnants of the Hello, Dolly! set at 20th Century Fox. He was open, down-to-earth, and quite unimpressed with his surroundings, though he had choreographed the film. He did talk about the casting of Irene Molloy in Dolly! that he didn’t agree with, that he was suspicious of, but accepted it. He mentioned something about working with Julie Andrews in Star! but nothing nasty. Just pondering the act of working on a number. He was a realist about the big collaboration that gets a show on, a bit cynical without being sour.

Our final set meeting was in the rehearsal halls after we were in process. He was working with his assistants on dance moves. He was in his element, secure, with no attitude.

For the scenery he was not forthcoming about details or concept, and surprised me later on by saying he had just read the second act the night before and what the hell were we going to do? Had he never read it before? Oh. They hadn’t prepared me for that in design school.

I suggested basing one scene on the painting Wedding on the Eiffel Tower, to which he was open, but not terribly interested in intellectual approaches. Okay. Also not like design school.

He spoked delightedly of his wonderful day off where he had installed a sprinkler system in his lawn. He loved working with his hands. I liked doing things with my hands, too.

“John, you’ve got to help me … The show has five big numbers. I can’t choreograph five — I can choreograph two, I can do staging for another, but the other two will have to be all props.” And so it was to be.

He then had to take a nap, “no need to leave, you can continue working with the assistants, John.” He leaned a folding chair against the wall and went to sleep sitting up — for about ten minutes. He woke up refreshed. Back to work. I was impressed by such discipline.

The producers didn’t give me a car (cheap young designer to take advantage of, I guess) until the shop carpenters complained. Los Angeles is a big city to do a show in. We went forward. I was lost, but we went forward. Robert Randolph looked cooly at me and I realized that he wasn’t about to help me at all. He was caught, his New York career over, and I was a silly interloper to him, now possibly taking his California jobs away from him. I was an innocent abroad, I knew. He had a fifties buzz cut, I had a hippie cloud of red hair.

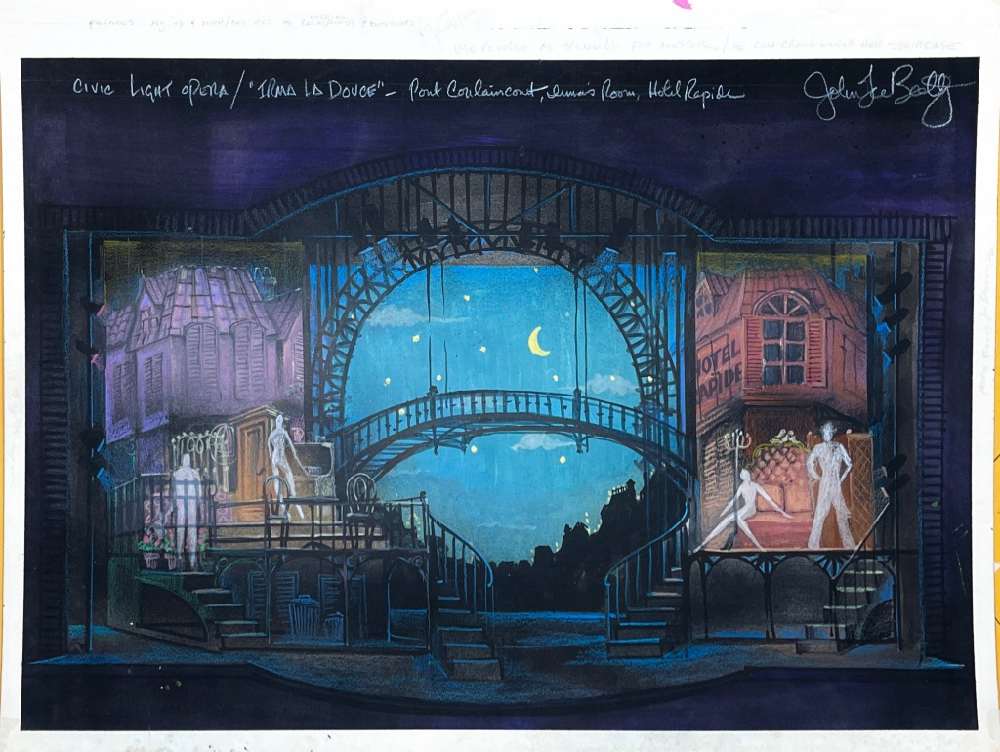

Eventually in technical rehearsals, I was in agony. The set was a compromise, albeit oddly, with a fairly good ground plan. The conceit being that we were in a big black backstage, we then could have Parisian ‘scenery’ show up and revolves turn with props and partial painted scenery showing our scene.

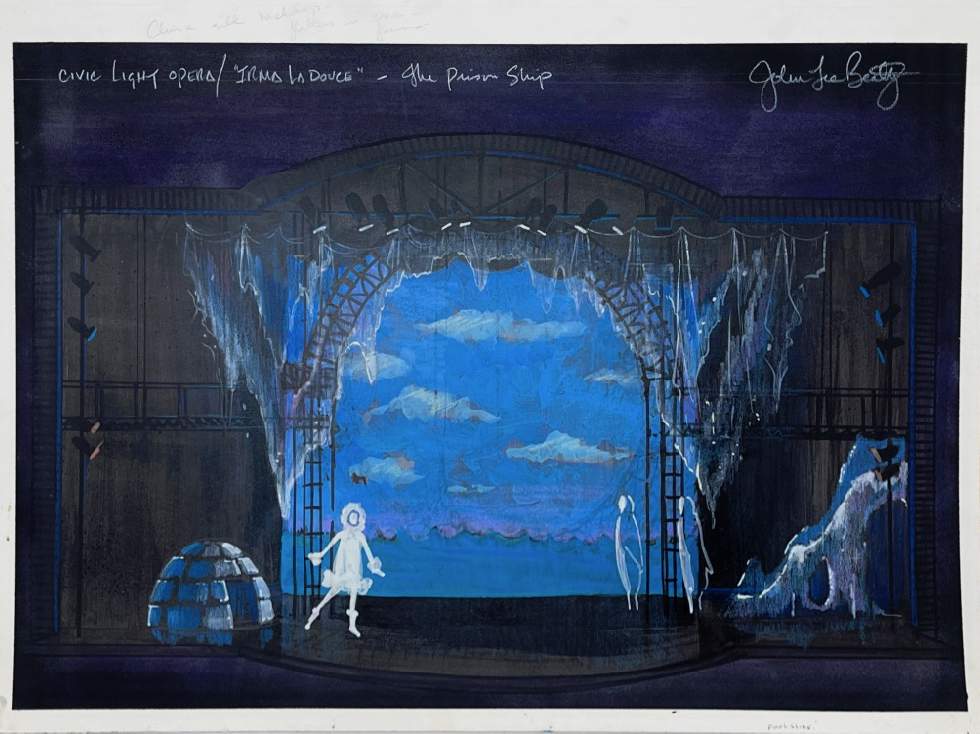

One case of ‘prop’ choreography, Michael asked me to get a pool slide, make it look like an iceberg, and let some ‘penguins’ slide down it, propelled across the stage. Fantastic idea, it stopped the show.

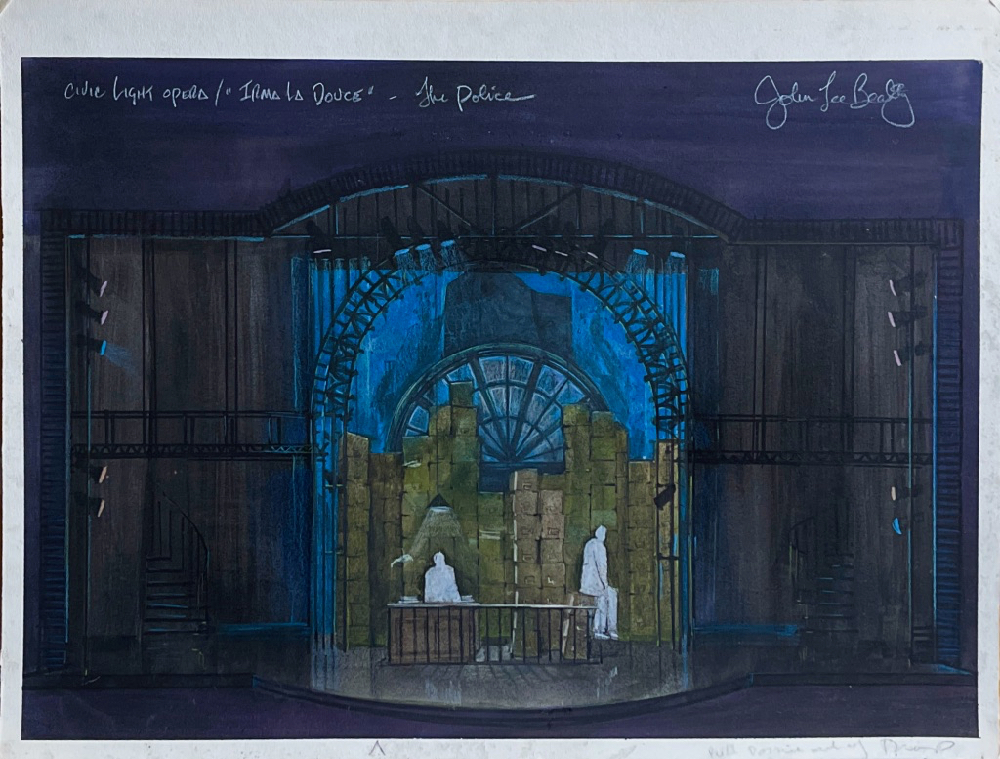

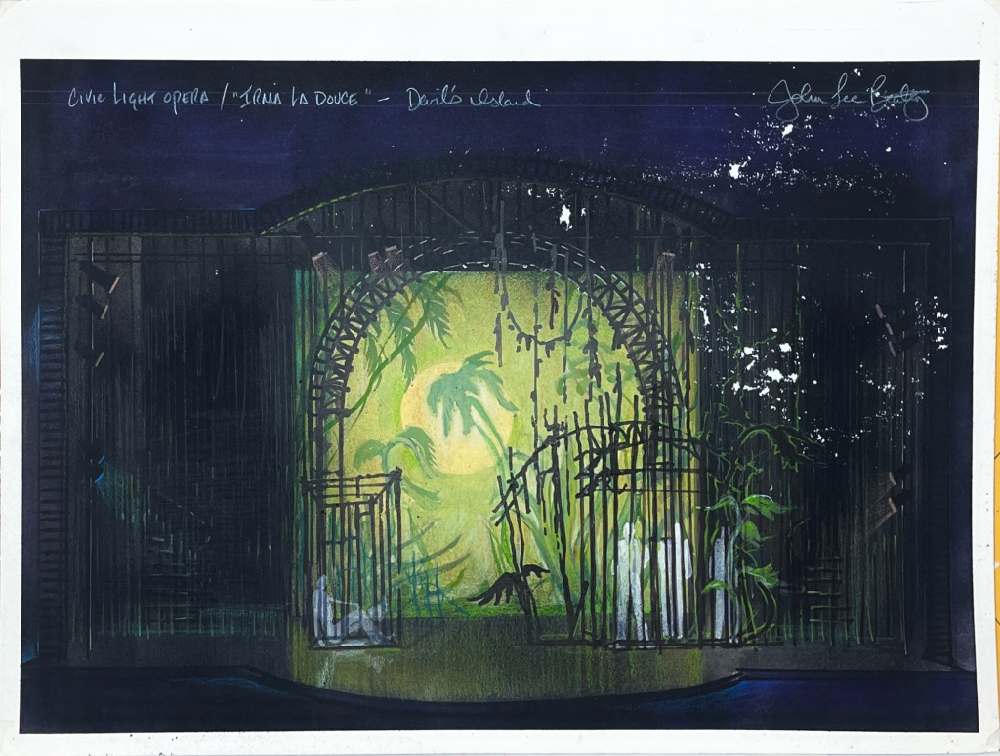

Enlarge

Scenic Rendering by John Lee Beatty

We rehung the order of the flying pieces every day, as Michael figured out his spatial priorities. The show carpenter who built the show was kind and old-fashioned. If there was a problem, I was supposed to describe it to him, not point it out to him together from out front. His code of behavior said that how it looked out front was my job, how he fixed problems was on his turf, backstage.

The stagehands were making lustful noises about the arrival of the tall, beautiful showgirls, who the producers had cast in Las Vegas. They arrived, perfectly pleasant, tall and stunning, and the stagehands ran in the other direction and all got a crush on a little dark-haired chorus dancer. The chorus members explained that to be a Las Vegas showgirl one had to get the exact breast implant required for work, but that the job involved little real show dancing. It was hard to remember why they were there.

The dancers worked, sometimes very physical Michael Kidd choreography, sometimes a lot of prop lifting and twirling, as promised. The props were dancing as much as the dancers. One of the wonderful stage hands finally wept after trying and trying to get breakaway tables to do all that Michael wanted in the bar brawl choreography. Michael sincerely sympathized with him, he loved workers, and we all went forward doing even more hard work for him. There was a wonderful opening number of dancers carrying unending props, more and more, across the stage. Michael had choreographed as he promised!

There was dance scene on a revolve, backed by a wall of twinkling, exploding lights. I designed and supervised the building of the lighting effects, and Mr. Randolph took all the credit for them … “hmm. I learned something there.“ The revolve, Michael loved, but it never went fast enough for him, the stagehands finally replaced the crank with an electric bolt driver. It worked. It worked extremely well. Michael was delighted, his eyes alight as it was spinning faster and faster, but now the dancers were getting thrown off the revolve, some clasping each other in the center, ’til centrifugal force threw them into the wings. A screaming halt.

“Right.” Michael says, ”Too fast, guys.”

The stagehands’ favorite, the little wren, was off to the hospital and we pushed forward.

But Michael had no malice, only a vision.

The show eventually opened, and Priscilla Lopez, our wonderful navy blue clad Irma was dwarfed upon occasion by the sparkling Amazonian showgirls. Clever expedient ‘Michael Kidd’ staging was speeding up the repetitive second act, but nobody’s heart was in it. The show looked dark, purposely underlit to the point that even the producers asked Randolph for more light. The scenery was not always inspired to begin with, ground plan aside. I think Mr. Randolph wanted the scenery not to look very good anyhow. Mr. Randolph got the head carpenter fired, and on opening night the producer dismissed me with, ”Congratulations, you have fulfilled the terms of your contract.”

Irma La Douce at the Civic Light Opera - Scenic Renderings by John Lee Beatty

Once upon a time…In Los Angeles, my show on the Light Opera stage, I was crying in my hotel room at night. Not good enough, I thought. I suppose I learned to keep my head up, though painful. I used to punish myself by going all the way to the upper reaches of the three thousand seat theater. Fully one third of the audience couldn’t see Priscilla’s face. The scenery, sadly, they could see. I confided my pain to my mother, who with miraculously attained show business wisdom stated, “Johnny, it’s only Los Angeles. Nobody will see it.”

Years later, the Light Opera era gone, Feuer and Martin era gone, all moved on, I was approached by Michael to do another show. I looked into his face, asked how he could ever do that, as flattered as I was. I had messed up the show big time, and I liked him so much.

“Oh, John, it was fine, you are too hard on yourself, you only made one mistake.” Only one? I still wake up in the middle of the night regretting my decisions. “The masking should have been red.” In a second I realized I had neglected ‘joy’ in my design. Good note from Michael. The rest of the show’s failure? “Not your fault.” He was so matter-of-fact, saying, no problem, we are all here to work, showbiz happens, I like you.

I like you too, Michael. Workers go to work. Ignore the rest, but leave room to create joy.