Enlarge

In 1973 you walked around the corner from the subway stop at Nostrand, down Herkimer Place to an old roller rink. It was best if you walked in a group, as it was the seventies and Bedford-Stuyvesant wasn’t an easy place. The building next door was burnt down overnight. All the scenic shops were in chancy neighborhoods, as shops required a low rent and a very large open space, hard to find in New York City, even in a recession. For Nolan’s Studio, a former roller rink was perfect, column-less and the wooden floor no matter its present condition could have canvas backdrops stapled to the floor anywhere and everywhere. The ceiling leaked in places, so the backdrops that were supposed to be ‘watercolor’ in style were whacked down to the floor in that area, as an overnight splash of extra water from the leaking roof wouldn’t pervert the paint style too much. Up a precarious stair, the wooden break room was unevenly suspended from the rafters, as were the offices at the other end, from the ceiling. It was pretty rough — the unheated men’s room fixtures constantly leaked, so in the winter there was a solidly frozen cascade of ice in place of any usable water in the toilets. The guys used the ladies room then. We painters wore old clothes, sometimes in layers, sometimes even with hats and fingerless gloves as the space was weakly heated, if at all.

A painter painted standing up, using a bamboo extension for brush or charcoal work. It was considered unprofessional to squat, and painting could be really hard on the knees. To balance, or to look supremely experienced, the un-busy hand went into the pocket of the work pants, unless one had to hold the painter’s elevations one was copying. The designer’s painted elevations of a backdrop were gridded in 1/2 inch = 1 foot scale, and to paint a “drop” we drew the enlargement in charcoal on enormous brown paper the size of the finished backdrop, usually about 27 feet by 36 or 38 feet. Drawing was the very important first step, since drawing straight onto the actual fresh canvas ‘blank’ was not allowed or a good idea, as only the perfected layout would be transferred to the canvas. The big paper backdrops were called ‘pounces’ as one took a ‘pounce wheel’ which was a rolling disk with sharp points fixed with a handle like a pizza wheel, and one followed the lines of the charcoal drawing making small regular holes. A bag of powdered black charcoal was then used to softly force charcoal dust through the small holes, thus transferring the drawing onto the fresh canvas to be painted.

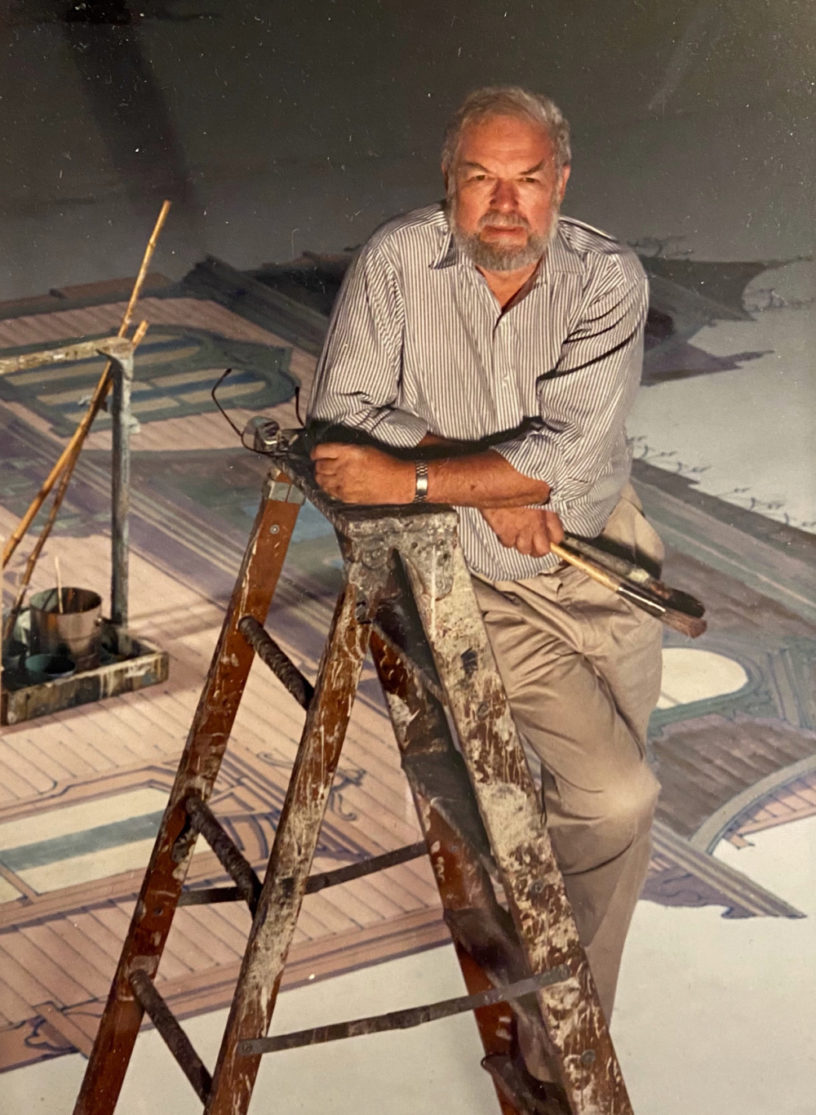

The ‘pounce’ had to be right, and once finished it was very valuable, as it took days of work not only to cover such a large area with drawing but also to perfect the details of the designer’s intentions. The miniature elevations were in watercolor, gauche or ink, and were painted by masters of painted design. The most famous designers’ work was so well known, that certain artists could draw in their style, or understand their ‘shorthand.’ An Oliver Smith crosshatch of seven lines would be re-interpreted by an assigned artist in full-size to 9 or 11 lines as the painter was familiar with the particular designer’s artistic intention. The scenic artist might even take one rendered Oliver Smith tree and create 7 other variations to fill in empty spaces in the same style. If the designer was late with details, the Nolan’s owner and master painter Arnold Abramson might even pull open a drawer full of the designer’s other work and grab a convenient tree to copy. Paint was not to be delayed.

The paper ‘pounce’ was valuable for another reason, for if a show were to be a big hit, the pounces could be used to duplicate all the pieces of painted scenery without endless redrawing. Weeks of work would be saved, and the designer’s intentions would be preserved. There was a tall, long rack on the wall with long, long rolls of hit show paper pounces. The ownership of these pounces was important. I asked, as a naive student, why the Oliver Smith design for My Fair Lady had different numbers of cross-hatched lines painted behind Julie Andrew’s head in the final frequently photographed study scene. I had noticed in the second national company that there were more crosshatched lines than the original. The answer, from Arnold Abramson, after a kindly but unmistakeable roll of the eyes, was that the original shop went into contested ownership and the pounces could not be reused as they were held as contested assets. So all other successive productions of My Fair Lady had matching cross hatching from the new pounces, which still existed, twenty years later. And he should know, as he was the touch-up artist who followed the scenery to the tryout in New Haven. Interestingly, he said that most of the paint notes in the tryout actually came from the costume designer, Cecil Beaton.

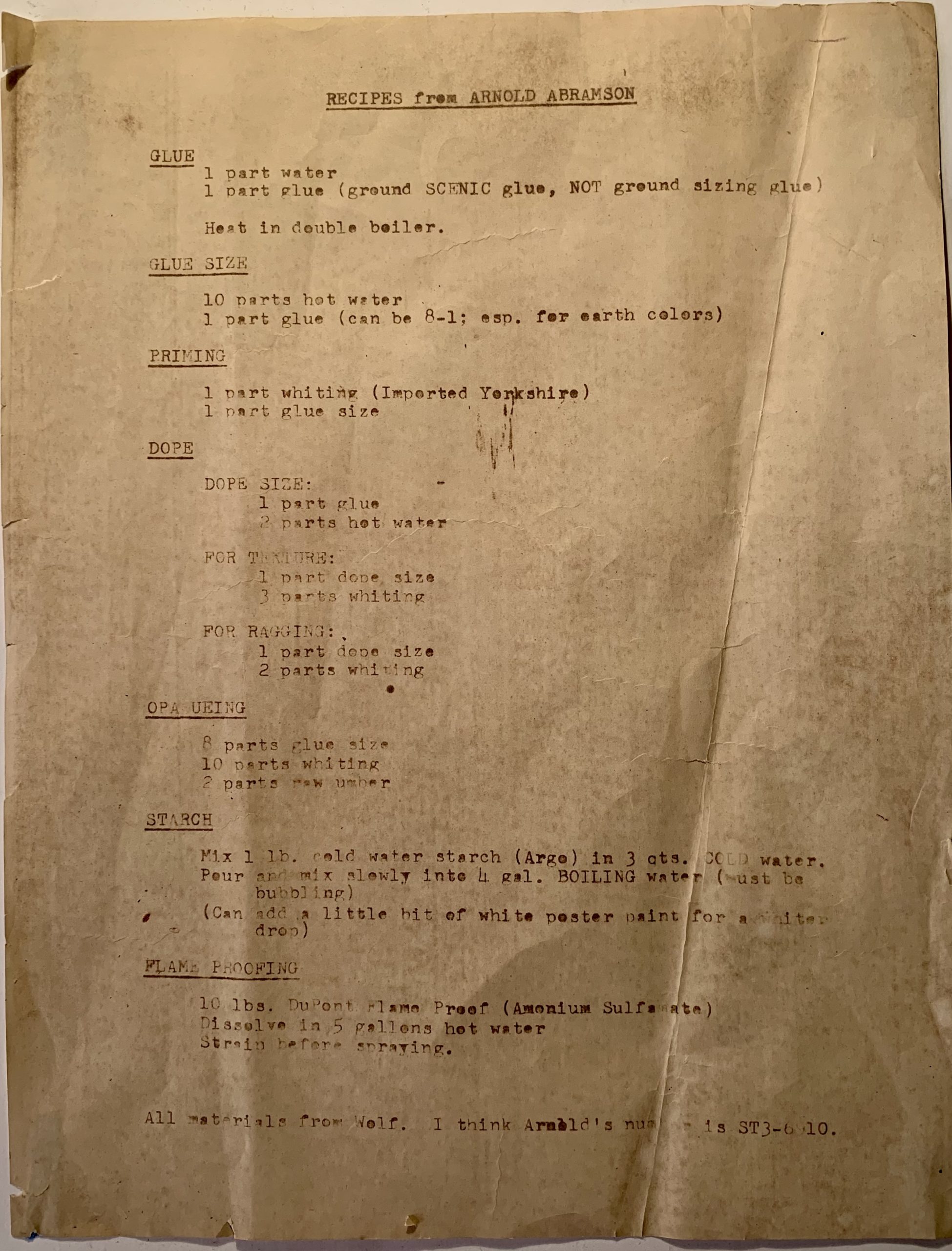

For painting a backdrop, a huge pristine piece of canvas was stretched and squared on the floor, stapled over a protective layer of absorptive ‘bogus paper.’ The drop was primed with thin paint, or in the case of dye-painted translucencies, liquid transparent starch, which was called ‘bull come’ in honor of its comparable viscosity. “Add a tablespoon of white poster paint to clean it up” was the secret too, for preventing the starch from yellowing on the canvas. This primed canvas was what the pounce design was transferred onto with great care.

As every penny counted, sometimes the canvas had a horizontal seam. Seamless canvas was so expensive then, long before labor costs made sewing the seam more expensive than the wider product. Clever designers hid the seam as a horizon line, or power lines, or any horizontal they could think of.

On the far wall, open gas jets were heating water in multiple garbage cans, and rows of powdered paint, cans of casein paint, and bottles of aniline dye were on a range of shelves. Every color of metallic powder. Mica ‘Flitter’ and asbestos powder. There was granular animal glue, paraffin, chalky Dutch whiting, charcoal sticks, white chalk, and charcoal dust. Gold leaf for those who could afford it.

A ‘Paint Boy’ tended to the bins of brushes, and was constantly cleaning and preparing and hand-pumping Hudson sprayers. The brushes were constantly cleaned and rotated, but an intent little Orthodox Jewish man came in once every three weeks, hatted, all in black, carrying a doctor’s bag filled with rehabilitated ‘ruined’ brushes that he had bathed and combed back to life in his basement; he picked up the new ‘casualties’ as soon as he delivered the recovered ones. He was not even out the door before the most knowledgeable older painters had grabbed the newly soft, sable textured revived brushes.

Yes, many of the paints were toxic, and are long gone. Powdered asbestos made a wonderful fireproof plaster texture, let alone a dust cloud in your face as you stirred it. The cloud from the aluminum powder or the dry aniline powder caught in your throat a bit. And of course, an accident burning animal-based glue and water left an unforgettable odor for days on end. Fireproofing salts were tossed into paint and water, to be applied to the scenery, and we sometimes made sure by licking the canvas drops for the salty taste.

Mixing paint was a big undertaking. Samples of color were examined, carefully, but a mistake was expensive. Mixing the wrong amount was a second disaster. One time I desperately tried to match the exquisitely muted Art Deco colors of famed designer Raoul Pene DuBois, finally being clued in by Bob Motley the lead painter, that Mr. DuBois painted so fast that he never cleaned his rinse water, thus by adding a tablespoon of ‘filth’ (raw umber paint) I could turn my hot pink into a 1930’s shade of cyclamen. Very kind of him to tell me. Some of the painter stars wouldn’t share their expertise, and hazing of a tenderfoot painter was common.

Musicals and operas depended on the artistry of the drops to make them astonish. And some scenery painters, very good ones indeed, would only paint drops. Built ‘Units’ were for the lesser talents. Paint was so important that certain designers like Oliver Smith or Boris Aronson, would specify which painters were to paint their drops. I was not allowed near a Smith drop, glorious in its free watercolor flair. And Boris Aronson specified who was to paint the tree trunk, and who was to paint the foliage of his trees. Arnold Abramson wickedly switched the two paint teams, trunks and leaves, and quickly switched them back as Boris entered the shop from the far door. Boris approvingly said “See I told you so!” and Arnold agreed with an innocent smile, that the trees were perfect. It was a matter of a scenic painter’s artistic honor to Arnold that there were other qualified painters able to paint Aronson trees, even if secretly.

Some of the painters were actual legitimately recognized gallery artists, as was Arnold Abramson himself. And some of us were ‘scenic artists’ only, with our own modest skills. I was good at painting folk or naive art, Chagall, Grandma Moses, or Red Grooms. And, most importantly, I was fast. Fast was important.

Arnold loved fast. We were paid 30 dollars an hour in 1973. And overtime was double. That was a lot of money—and theater was not doing well. There really wasn’t enough work, but when it was there it was good money. We did not sit down, ever, while being on the clock, and you never knew when the scenery was going to be deemed ‘finished’ by Arnold, and disappear into a waiting truck. You painted the entire surface of a backdrop at the same degree of detail at all times, as you never knew when it would be pulled up, and it couldn’t look unfinished. And if a designer didn’t come in early enough to approve a paint job, they might find their scenery already in the truck making its way to the theater. At the end of one day, still finishing the minutes of our last working hour, we were handed cardboard to flap in the air to dry the drop, rather than sit down or leave early. Nothing was ever wasted, not paint nor work hours.

It confused me one day, as I was positioned near the entrance door to the shop, painting a Red Grooms-like detail on a Santo Loquasto set, that I was not chastised by Arnold for slowing down and gossiping with Santo as I painted. The shop was bustling, getting Santo’s musical finished that day. Santo, seeing me first by the entrance, gave me a few paint notes, but mostly chatted about mutual designer interests. This went on for a good twenty minutes or half an hour. I later apologized to Arnold for my behavior as I had seen Arnold eyeing me from across the room as he busily rushed about. I felt guilty for keeping Santo, and especially for not painting faster, seeing across the room so much hectic activity. Arnold told me not to feel sorry at all, that he had engineered my painting position knowing that Santo would see me first and would be tempted to stop to chat. Meanwhile Santo could not see how much ‘finished’ scenery Arnold and the crew had hustled into the waiting trucks. Santo never had a chance to give time- (and money-) consuming notes on half the scenery.

Getting the painted scenery out the door was important, but Arnold was the best painter in town. The house style was clean, fresh, perfectly artistic, but never over-worked. Once, as the paint crew were cleaning up to go, having finished a Baroque backdrop, I spied Arnold picking up a brush and quickly giving a cherub three extra brush strokes. Not breaking union hours, he was determined that in the last working minute the cherub would be deliciously, plumply perfect. He would invent paint solutions that were quick but extraordinary in their freshness and simplicity. The backdrops were alive.

The dusty paint shop walls were hung with hundreds of stencils: many kinds of brick, damask, bricks in perspective, damask in perspective, letters, and leaves. Before computer printing, one had to have a series of dot matrix stencils to simulate enlarged photography. Designers were longing for the then very difficult illusion of a blown-up newspaper photo. It required a deft touch and sure calculation to make the illusions work. And, in the days of painted not built ‘brick,’ Arnold rued the effort of painting endless ‘brick walls.’ The designers, Oliver Smith, Jo Mielziner wanted each brick a slightly different color which required hours of glazing to achieve, or Robin Wagner who wanted bricks perfectly, precisely uniform—almost more difficult to achieve.

Soon painted canvas scenery was to go out of style, built scenery was gaining. Famous designers were no longer known for their painting style. Shopmen and carpenters no longer smoked stogies. Reverence for paint was leaving us too. The older painters who were now willing to share their old time secret painting techniques, couldn’t find willing young ears to listen. Paint now came in cans, and many of the older paints were forbidden for their toxicity. There is still joy found in a good paintbrush , but some of them are just thrown away after use.

Arnold Abramson finally lost the Nolan’s shop, and modern scenic shops became heated and even had working plumbing. Arnold went on to continue scene painting until his knees gave out in his eighties, and after that continued to paint oil paintings past his eyes giving out. In 2015, Arnold won a lifetime achievement award, a Tony Honors for Excellence in the Theatre.

He loved painting. He loved paint. He spoke the word with reverence and joy. Paint.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Before I ever painted at Nolan’s I knew Arnold.

In 1973 I joined the union, United Scenic Artists Local 829 as a scenic designer after the annual examination. I also joined as a scenic painter after taking the paint exam. Arnold had been my scenic paint teacher on Saturday mornings at Yale School of Drama. The class met at 8 a.m. on Saturday morning, so sometimes I was the only student who showed up. I loved the class so much, that I shyly asked if I could repeat it the following year. Arnold realized he had a ‘live one’ and we bonded forever. He lent me the brushes with which to take the union exam and coached me on it, telling me how to take the exam and what they were looking for. I had no idea he was checking me out as a painter to hire later. I could ask him questions that no one else had answers for.

Arnold, gruffly supportive, also once told me in one brief sentence what was wrong with one of my design works. He was so right that I have never told another soul what he said. Never. He could ‘see’ designs and designers like nobody else.

I painted off and on at Nolan’s when no other job presented itself. I loved it. I was still painting off and on into the late seventies, and even later. I went to the shop to paint the morning after my fifth Broadway show opened, Ain’t Misbehavin.’ One of the crustier old painters sidled over to me to say that I had a huge hit and that I didn’t have to paint in the shops anymore. Not long after, I was way too busy designing to return to Nolan’s as a painter, much to my regret. I think painting scenery is a noble profession, and I love paint too, just as Arnold did.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Anticipating a particularly painful opening of a musical, I decided to “get lost” in Europe for three weeks. I booked the ticket before the opening night. I was right to do so. It hurt. I told Arnold of my decision and he humphed a bit, as he had seen more than his share of tough times in the theater.

Arnold asked if I was going to Italy on my escape and said that if I did, he had a bit of advice for me. He said that everyone would be ooh-ing and aah-ing over the artworks from hundreds of years ago. He told me that I should look at them with a critical eye. “Just like us, they sometimes had to paint a lot –like on a rough afternoon in the shop. They had a deadline , too, and had to cover a lot of area. Not all of it could be good. Just being old doesn’t make it great.”

A week or two later I was entering the Pitti Palace in Florence. There was a guide pointing out the frescoes on the ceilings of a series of rooms, a lot of rendered vines. Old scenics would call that “lettuce” or “salad.” The tourists were looking up ooh-ing and aah-ing as if on cue. Wandering alone, all I could do was think of Arnold. If you ignored the provenance, it did look like they had cranked it out fast on a bad Wednesday afternoon. He was absolutely right. They had the same paint problems we did. Of course, they were in the same line of work.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The book, “Designing and Painting for the Theatre” by Lynn Pecktal (Holt, Rinehart and Winston) has pictures of painting at Nolan’s. And more paint recipes!